Opinion: Slow homes, next design revolution

At its best, slow home is not about consumption; it’s about deceleration, an act of resistance

By Viiveck Verma

The design world has always had its obsessions. Minimalism. Industrial chic. Biophilia. But just as the fast fashion backlash gave birth to slow fashion, and the wellness fatigue made us reconsider what self-care really means, architecture and interiors are entering their own reckoning. The next design revolution is not about spectacle, novelty, or even style. It is about stillness. It is about the slow home. A slow home is not simply a house designed to look serene, a beige-washed space with neutral linen drapes and artisanal ceramics, ready for a magazine spread. It’s a home designed to be lived in, not performed in. It prioritises longevity over trend, intimacy over display, and sensory comfort over aesthetic perfection. It is, at its core, a refusal of the culture of acceleration that has seeped into our living spaces.

Cultural Philosophy

The origins of the slow home movement trace back to the early 2000s, when Canadian architect John Brown and his colleagues coined the term in response to what they called fast housing — mass-produced, poor-quality, car-dependent suburban developments that valued square footage over quality of life. But in the last few years, the concept has evolved beyond urban planning into a broader cultural philosophy. The pandemic, with its enforced stillness, brought our homes under a level of scrutiny few had experienced before. The cracks weren’t just literal; they were existential. Did our homes support rest, or did they merely serve as storage units between commutes? Did they help us feel anchored, or did they amplify the churn of our digital, overstimulated lives?

In the age of Instagram interiors, where every corner must be ‘styled’ and ready for public consumption, this can feel almost radical

Slow homes offer an alternative. They are built or adapted with careful attention to how space feels at different times of day, how light shifts, and how air flows. Materials are chosen for their tactility, durability, and low environmental impact, think limewashed walls, reclaimed wood, natural stone, and low-VOC paints. Layouts are oriented to promote natural ventilation and human connection, not just resale value. There’s a certain quiet intelligence in the way a slow home is planned: less emphasis on grand entrances and more on the everyday pathways between kitchen, work nook, and garden. Crucially, the slow home resists the tyranny of constant visual stimulation. In the age of Instagram interiors, where every corner must be ‘styled’ and ready for public consumption, this can feel almost radical.

Mismatch Embraced

A slow home may have empty walls. It may have mismatched chairs, not because mismatching is a trend, but because they were acquired over time. Objects in a slow home tend to carry memory, not marketing value. You don’t replace the sofa because a new silhouette is in vogue; you reupholster it in a fabric that will age well with use. Environmental sustainability is baked into the ethos, but not in the performative, greenwashed way that’s often sold to consumers. A slow home is inherently sustainable because it’s designed to last, physically, emotionally, and culturally. The embodied carbon of construction is reduced through adaptive reuse and careful material sourcing. Energy efficiency comes from design intelligence, deep eaves, cross-ventilation, and passive solar orientation, rather than from tech-heavy retrofits alone.

In this way, slow homes align with the circular economy: building less, building better, and maintaining what exists. But perhaps the most profound aspect of a slow home is psychological. Our built environments shape our behaviour and mental states. Fast homes, with their open-plan living areas that leave no space for privacy, or their oversized footprints that demand constant upkeep, often create stress. Slow homes, in contrast, are designed to calm. They create pockets of retreat, corners for reading, and thresholds that allow for transition between activities. They allow silence to exist without feeling empty.

There is, of course, a risk that ‘slow home’ becomes yet another lifestyle brand, another aspirational label attached to expensive products. The irony of commodifying stillness is not lost on anyone. But at its best, the slow home is not about consumption; it’s about deceleration. You can create a slow home in a 400-square-foot apartment by reducing clutter, arranging furniture to maximise natural light, and choosing a palette that soothes rather than shouts. You can make it in a rental by investing in textiles and objects you’ll keep for years, rather than cheap décor destined for landfill.

Rooted in Traditions

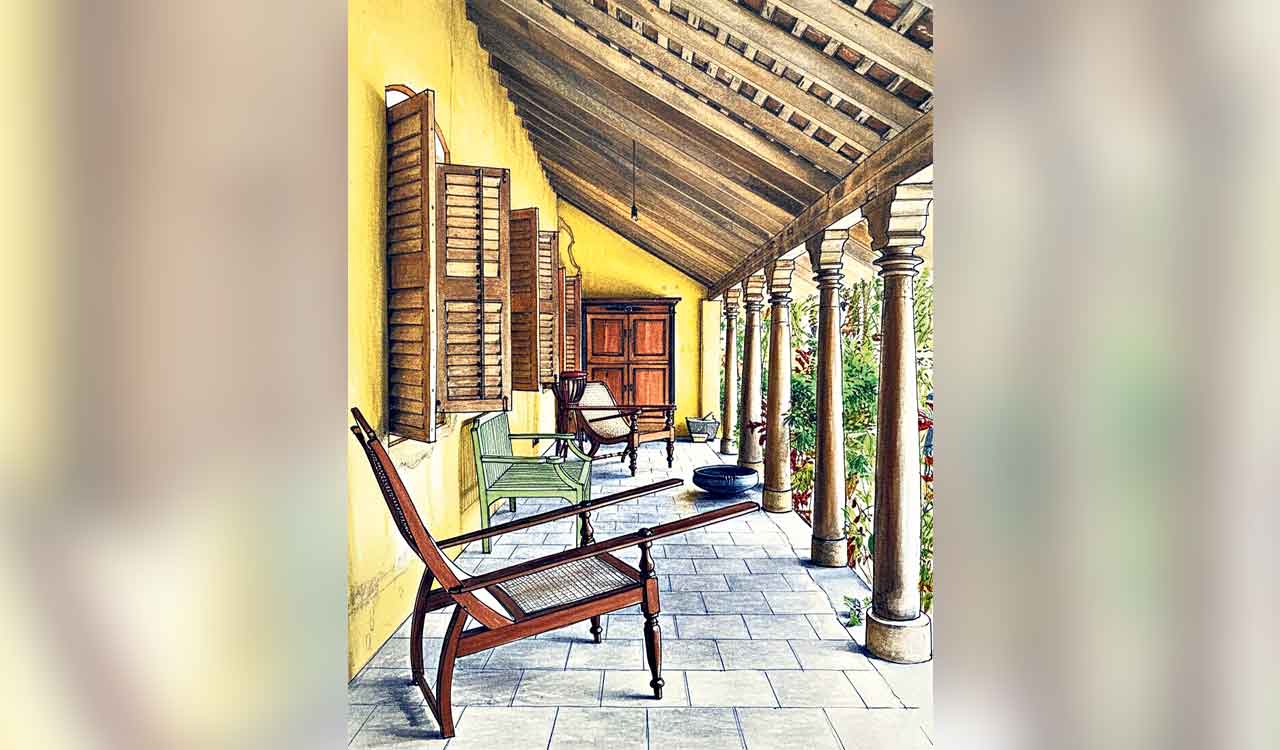

What’s striking is that the slow home philosophy overlaps with traditions that have existed for centuries in cultures around the world. The Japanese concept of ma, the space between things, and the Scandinavian idea of lagom — just enough — both echo in slow home principles. Mediterranean courtyard houses, with their shaded, inward-facing gardens, are another precedent. Even the humble Indian verandah, where life spills between indoors and out, offers lessons in slow living. These are not trends; they are wisdoms we’ve allowed ourselves to forget in the rush toward novelty. In an economy that thrives on constant renovation, the slow home is an act of resistance. It asks us to live with things, to mend rather than replace, to accept a degree of imperfection. It rejects the false urgency of ‘new season’ interiors in favour of timelessness that evolves naturally with the lives inside it.

We live in an era where homes have become backdrops for productivity rather than sanctuaries from it. The slow home creates spaces that aren’t just shelters, but anchors. Places where the hours lengthen, the noise recedes, and life, uncurated, unhurried, can finally happen. If the design world is ready for its next revolution, it won’t be heralded by the next ‘it’ colour or a viral furniture line. It will arrive quietly, in the hum of a ceiling fan on a summer afternoon, in the worn arm of a well-loved chair, in the calm of a room that feels like it’s been waiting for you, not your camera.

(The author is founder and CEO, Upsurge Global, co-founder, Global Carbon Warriors and Adjunct Professor, EThames College)

Related News

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

Opinion: Lives in limbo — Myanmar and Manipur refugees in India’s northeast

-

Opinion: US-Iran war — the cost of ignoring history

-

Major pipeline leak disrupts water supply in Hyderabad suburbs

6 mins ago -

Telangana Women Moto Bikers celebrate Women’s Day with vibrant gathering in Financial District

14 mins ago -

IIMC Khairatabad conducts Online Commerce Talent Test with global participation

14 mins ago -

From Lagacherla to Madhu Park Ridge, land acquisition disputes haunt Congress government

19 mins ago -

Smoke emanates from TGSRTC bus in Karimnagar district; passengers shifted safely

30 mins ago -

Government teacher found hanging in Kothagudem; family alleges foul play

34 mins ago -

IHM Hyderabad opens admissions for B.Sc. Hospitality course for 2026–27

1 hour ago -

Sharjeel Imam gets 10-day interim bail in 2020 Delhi riots case

1 hour ago