Promises to keep and politicians

The judgment of Delhi Court on enforceability of promises made by constitutional functionaries could have a big impact

On August 5, the Delhi High Court held that the promise made by the Chief Minister in a press conference amounts to an enforceable promise. The Chief Minister can be held liable to the promise as a single judge bench comprising Justice Pratibha M Singh observed, “the promise/assurance/representation given by the CM clearly amounts to an enforceable promise, the implementation of which ought to be considered by the Government.”

The instant case arose when the CM, at a press conference in the wake of the Covid pandemic, requested all the landlords to defer the collection/demand of rent from the poverty-stricken tenants. In pursuance, he made an assurance that the government would pay rent on behalf of the tenants if they are unable to pay on account of poverty.

In this context, it is necessary to extract the exact assurance he made on 29 March 2020. He said, “In a month or two when this corona and let’s assume after this entire mess is over, if a tenant has been unable to pay rent due to poverty, I assure you the Government will pay for it. I am talking about those tenants who may not pay rent due to lack of means.” (English translation)

Can a mere political statement by the CM be the basis for the doctrine of legitimate expectation in the absence of a government policy or an executive action or a government notification per se?

Supreme Court’s Stance

Let us look into what the Supreme Court has said in this regard in its decisions. Considering the loose interpretation given by the Delhi High court, it is also imperative to look into assurances given by politicians, especially by the Prime Minister, which can be enforced.

In the case of Motilal Padampat Sugar Mills Co Ltd v State of Uttar Pradesh and Ors, the Supreme Court crystallised the doctrine of promissory estoppel. In this case, the petitioner sought to enforce an assurance provided by the State government that it would give a partial concession in sales tax if a new vanaspati factory is set up. The said assurance was reiterated to the petitioner on several occasions. On particularly one occasion, the then Chief Secretary of the government stated in a letter that the petitioner could “go ahead with the arrangements for setting up the factory”. Later, however, the government went back on its policy.

The Supreme Court held that ‘where one party has by his conduct or words made to the other an unequivocal and clear promise that is intended to affect a legal relationship to arise in the future, intending or knowing that it would be acted upon by the other party to whom the promise is made, and the other party so acts upon it, the promise would be binding upon the other party.”

Enforceable Promise

In the instant case, the Delhi Chief Minister asked the landlords to postpone the rent of tenants who are unable to pay due to poverty for 2-3 months. After the corona is over, if a tenant is unable to pay the rent due to poverty, the government will pay on their behalf. As the Delhi High Court opined, “there would be a reasonable expectation on behalf of the citizens to reasonably expect that an assurance or a promise made by a senior constitutional functionary, not less than the CM himself, would be given effect to. In the Covid-19 pandemic, several landlords and tenants would have relied on the assurance given by the CM.”

In the present case, it is not the positive reply which is arbitrary, but the indecision, which the court held to be contrary in law. As the present case dealt with the fundamental right related to the Right to Shelter during a pandemic, the court accentuated the need of placing the principles of legitimate expectation on a higher pedestal.

At last, reiterating the two pre-conditions for the promissory estoppel doctrine as laid down in the case of Nestle India: “(1) a clear and unequivocal promise knowing and intending that it would be acted upon by the promise; (2) such acting upon the promise by the promisee so that it would be inequitable to allow the promisor to go back on the promise.”

Setting Precedent

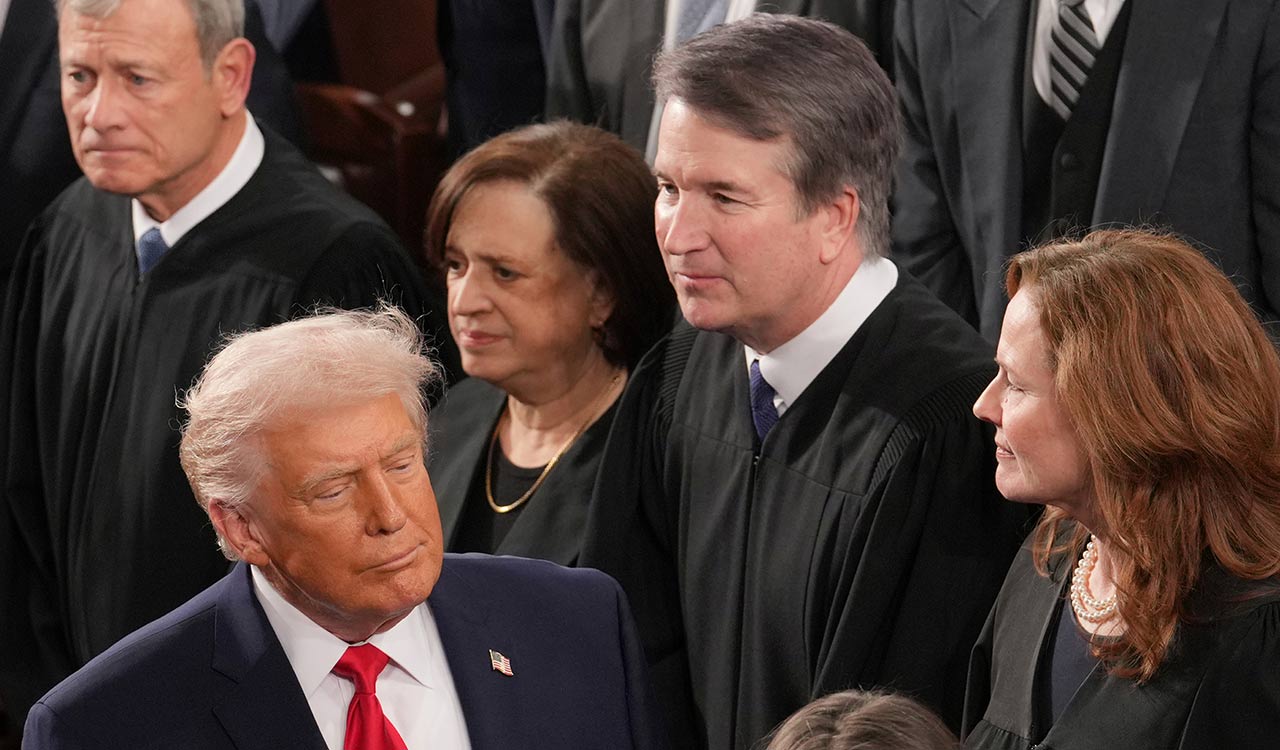

Coming to the issue of enforceability of the “puffing” made by politicians repeatedly in governance, the first name that comes to mind is that of our Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Up to 1,540 assurances were left unfulfilled by the end of the 16th Lok Sabha when the NDA-I-led Modi government was in power, as per an India Spend analysis of Parliament data. The government’s rate of fulfilling assurances fell from 84% in its second sitting in July-August 2014 to 10% in the last sitting in January-February 2019, as per the Committee on Government Assurances.

The promise might have acted upon some of the promises made. Be it Kisan Samman Nidhi, direct subsidy transfer to bank accounts of the underprivileged, affordable housing for all, or financial assistance for micro-businesses under the Mudra Yojana, the assurances have evoked enough trust of the people, which helped the NDA government buck the anti-incumbency wave.

For instance, Prime Minister Modi promised that the river Ganga would be clean by 2020 whereas, former Union Minister for Water Resources Nitin Gadkari promised that the river would be “noticeably clean” by March 2019. Mind you; all these assurances were reiterated by the different Central government ministers from various platforms in their official capacity on behalf of the government.

Then Finance Minister Piyush Goyal, while presenting the Interim Budget in 2019, said, “The government will make 1 lakh villages into digital villages over the next five years.” A wave of jubilations ran high, people were excited, and even some planned investments were made as Bharat was about to catch up with Tier 1 cities of India. However, the statement turned out to be a gimmick of sorts. In response to the RTI filed by Inc42, the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology replied that there was no such plan in a proposal form.

Kshijit Goyal

So, proper governance requires the government to decide on the assurances given by the ministers, and inaction cannot be the answer. The Delhi High Court’s judgment is an indication that similar statements made earlier by the other functionaries can be used to demand enforceability of the assurances. The judgment holds inordinate value to the potential litigants to claim accountability from the various State governments and the Modi government at the Centre on the assurances made.

(The author is third year BA LLB student at National Law School of India University, Bengaluru)

Now you can get handpicked stories from Telangana Today on Telegram everyday. Click the link to subscribe.

Click to follow Telangana Today Facebook page and Twitter .

Related News

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

2 hours ago -

SJFI national convention returns to Delhi with Hero MotoCorp as title sponsor

2 hours ago -

Delhi beats Hyderabad by nine wickets in BCCI women’s under-23 one-day championship

2 hours ago -

Hyderabad player Sowmith Reddy wins Unrated Chess Tournament at A2H Chess Academy

2 hours ago -

Editorial: T20 World Cup glory— rise of the Blue Tide

2 hours ago -

HC clears Ram Rahim in murder case, says CBI acted under pressure

2 hours ago -

Nampally court dismisses Sakala Janula Samme case against KCR, KTR

3 hours ago -

Bhoodan land row: 43 booked for violent protests in Khammam

3 hours ago