Rewind: Beyond Human Time

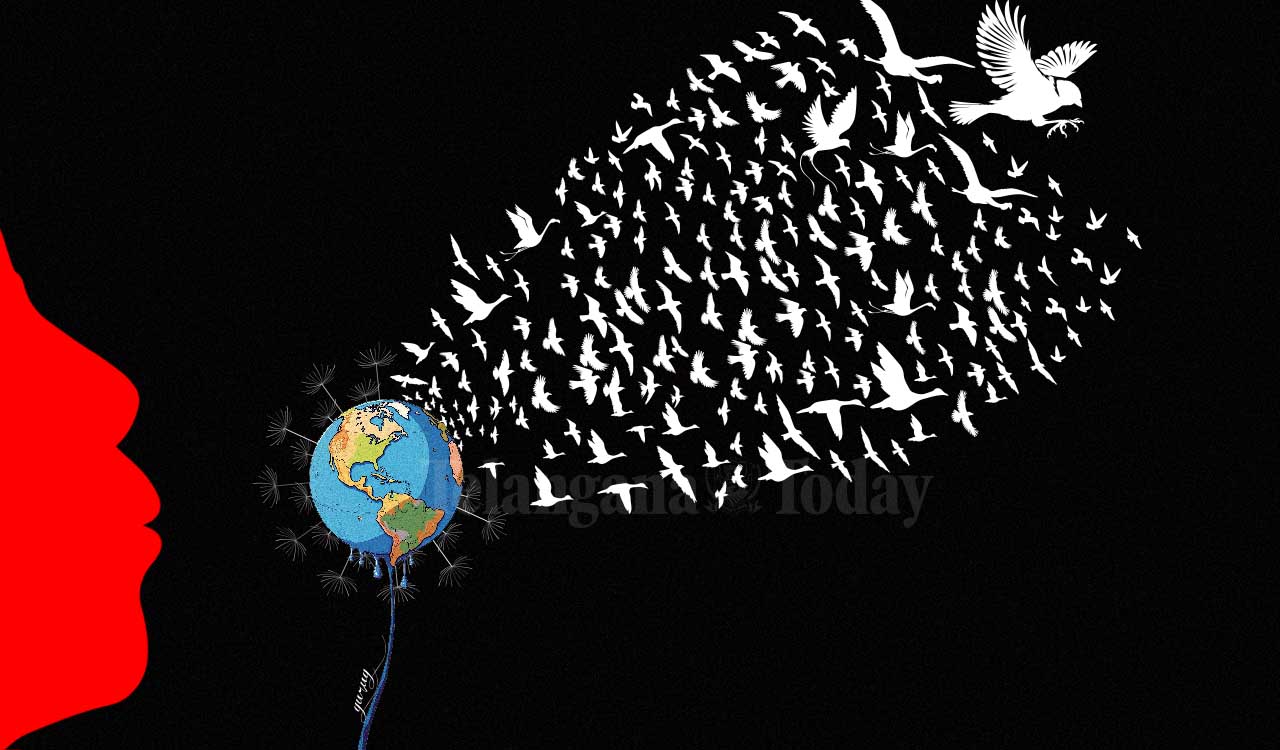

The oceanic in much contemporary fiction is the place of multispecies belonging and new becomings, and decentres the human

By Pramod K Nayar

While CEOs, present and former, are accused of being inhuman in their insistence on extended working hours, there is, at least in the world beyond humans, nonhuman, or shall we say, inhuman time. Science fiction and fantasy literature have always been concerned with time other-than and beyond the human, of time travel and parallel times. They are interested in multiple temporalities, or at least entangled temporalities where human and nonhuman times converge.

Also Read

This focus on nonhuman time but also nonhuman materiality that constitutes humanity and the human terrain in contemporary fiction is really an argument against anthropocentrism, the view that humanity is the centre of the universe.

Wreck Time

The oceanic in fiction opens up the ‘problem’ of nonhuman time.

In an early example, Jules Verne’s Aronnax in Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Seas is so overwhelmed that he is ‘able to set foot on one of the mountain peaks of that drowned continent [Atlantis]’. The sight makes him reflect on temporality. The ruins are ‘thousands of centuries-old and dated back to the great geological epochs’, and when he walks he ‘trample[s] on the skeletons of animals which had lived in the age of fables and had once upon a time sought the shade of leafy trees now turned to carbon!’

We believe, as earth-bound creatures, that time begins with the land. But novelists now explore what oceanic time means to humans

Later, they encounter a shipwreck whose ‘severed shrouds were still hanging from their chains’. There are still carcasses scattered around, one of a woman with an infant in her arms. It appeared, says Aronnax, ‘a gruesome sight … photographed in its final moments and he imagines ‘a number of enormous sharks, with fire in their eyes, bearing down on it, attracted by the lure of human flesh!’ Such sights of ‘shipwrecked hulks suspended in the water, slowly rotting’ and at lower levels of the ocean, ‘cannons, cannonballs, anchors, chains and countless other iron artefacts which were eaten away by rust’, some wrecks ‘encrusted with calcareous deposits’. Over a century later, Richard Powers in his new novel, Playground, also turns to the shipwreck to speak of time passing:

Life covered every inch of the twisted surfaces and turned them into high-rise dwellings. A brass ship’s throttle, its handle stuck to a speed that failed to save it, lay like some wild Miró sculpture caked in starfish and worms. Morays nested in the gun barrels. One ship’s crumpled mast was so coated with swirls of whip coral and anemones that it, too, branched as if alive. Troops of porcelain crabs skittered in formation. Nudibranchs slithered across bits of blasted deck as if some wedding had scattered hallucinogenic bouquets.

Ships and their submerged wreckage are the sites of the conciliation of human and non-human temporalities, of human and non-human rhythms. The coral encrustations, cadavers, skeletons and rusted iron are sites that are at once about the present and the past, human and nature, whether these are in the form of encounters with ship wrecks and their encrusted materials.

The subaquatic is a place of very different forces. In Peter Watts’ Starfish, Clarke recognises that residing deep in the Pacific is to acknowledge the power, specifically non-human power, that circulates through the realm. Clarke thinks: ‘There’s so much power here, so much wasted strength. Here the continents themselves do ponderous battle’. Watts points to the distinctiveness of the ocean: ‘Human machinery does not make energy … it merely hangs on and steals some insignificant fraction of it back to the mainland’.

The focus on nonhuman time, especially in under water fiction, is an argument against anthropocentrism

In these texts, Nature, so to speak, enters the (human) habitation or the ship in the form of flowing water, mud and various life forms. Whatever matter made up the human construction has been freed from its subservience to form: the ship’s various parts, made of various materials, are not any longer part of a functionality. The anchors, the cabins and various items in the wreck have erased the traces of the human hand due to the workings of Nature, but still resist entirely dissolving into Nature. Within the wreck, whether of the drowned city or the ship, there is the co-presence of the ocean’s rhythms and processes, thereby conciliating oceanic and human history.

A descent into the aquatic depths means an encounter with flows and materials that are of human, non-human and non-living origins. To travel beneath the surface is to encounter a whole world that shifts, alters and moves. One of the best examples of this underwater world where human power is extremely limited is to be seen in China Miéville’s The Scar. Miéville opens with an account of flows and interconnectedness of all movement and matter. And, as in the case of wrecks, human inventions and nature intertwine: ‘frost-crabs…forests of pipe-worms and kelp and predatory corals. Sunfish … Trilobites make nests in bones and dissolving iron’.

Miéville makes it clear that it is no longer possible to distinguish between Nature and the human-political.

Subaquatic Time

Other novels opt for more complicated ways of showing us nonhuman time. Larissa Lai invokes Buddhist understandings of and belief in reincarnation so as to disrupt any evolutionary time in her novel Salt Fish Girl. The time of the oceanic is within Nu Wa, the part goddess, part human. Slowly, Nu Wa’s mythic time will eventually become humanised. But the oceanic is also the source of interspecies memory. People are infected with bacteria that give them the memory structures of other, nonhuman, species.

The fish/human binary is blurred where the ‘memory disease’ of humans is described in the novel as ‘a bug that gives [people] the memory structures of other animals – fish maybe, or elephants’. Further, Lai adds cyborg evolutionary time (genetic materials, machines) to the mix in the tale. It becomes difficult. Therefore, to disentangle the time of the goddess Nu Wa and her human avatar, Miranda. Salt Fish time meets human time.

Instead of the fish world in Lai, Rita Indiana in Tentacle turns to the Condylactis gigantea, the Caribbean Giant Anemone. This anemone, a major life form that enables multiple commensals, is a deity, Olokun (which means ‘owner of the ocean’) and is described in the novel as ‘a marine creature that walked back in time’. Eco-warriors carry visual evidence of the crisis: photographs of ‘dying coral, stained and deformed like cancerous livers in a brochure for Alcoholics Anonymous’ even as ‘a site list[s] all the coral reefs that had disappeared in the tsunami of 2024 popped up on the screen’. The anemone-as-deity, the carrier of racial memory, represents a possible solution to the crisis.

In underwater fiction’s focus on shipwrecks, we are shown how Nature enters into, and alters, human constructions such as ships, how they are subject to nonhuman, even non-living forces

Another powerful novel about oceanic memory that is beyond human time is Rivers Solomon’s The Deep. Here the underwater species, called wajinru, are lifeforms evolved from the descendants of pregnant slaves thrown from ships during the Middle Passage. They have a periodic ritual called The Remembrance when they recall, through one individual, the memories of their community. The oceanic is the site of the collective/community memories, which are all memories of oppression.

Lai, Solomon, Indiana all seek to communicate the continuing pull and power of the ocean by referencing mythic and non-western, histories. These histories are, they suggest, more effective in organising identities and keeping alive both, histories of their races and the racialised structures they inhabited (colonialism, slavery, neocolonial oppression). In addition, these alternative histories also link human and nonhuman ecosystems by refusing to see human actions as distinct from their environment.

Reading Lai or Solomon, one recalls Derek Walcott also pointing to the oceanic sites of racial memory: the descendants of slaves see the ocean as the repository of their ancestry. In ‘The Sea is History’, Walcott writes:

Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,

in that grey vault. The sea. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is History.

Solomon and Lai suggest that the oceanic is the source of specific kinds of racial memory. By casting this memory as transmissible, they suggest that it is planetary in scope, because the world’s oceans flow everywhere, connecting everything. In other words, the world’s transoceanic memory contains histories of genocide, racism and oppression.

Entangled Time

But humans do not, emphatically, live under water. But the oceanic, as Blue Humanities scholars remind us, is the story and site of human origin, and, therefore, there is the oceanic in all life forms. So do we assume human time begins with the shore, away from the ocean?

Novelists like Larissa Lai and Nnedi Okorofar refuse to see the shores and land as distinct from the sea. In Okorofar’s Lagoon, she blurs all categories and elements: the ocean’s shores, mud, soil and water flow across borders and each other. She writes:

But the story goes deeper.

It is in the dirt, the mud, the earth, in the fond memory of the soily cosmos.

It is in the always-mingling past, present, and future.

It is in the water.

But which water is this? Is it only the bounded waters of the lagoon? Since water is boundaryless despite human attempts to mark boundaries, Okorofar seems to imply a transoceanic source for the dissemination of memory. Perhaps Okorafor is proposing an interconnected planetary memory here, one that cuts across regions, beings and time.

This fiction draws a transoceanic mnemosphere. The mnemosphere brings together multiples: ‘animate things’ like mermaids and mermen, sharks and whales, carp and various species of fish, reef and corals, and from deeper still, pearls, oil and minerals. All life forms and the non-living with their interspecies memories permeate the material contexts of water, mud, and land.

The ocean is a place of several kinds of histories, particularly horrific ones of the African Americans, whose ancestors were taken on the slave ships to the ‘New World’ — a voyage during which many died

The subaquatic novels show linkages, and the possibility of new kinships beginning under water. In Okorafor’s Lagoon multispecies kinship with life that emerges from the oceanic depths, or from the ruins on the ocean’s surface, is presented as a means of salvation. When Rivers Solomon’s The Deep ends, the humans on the surface come face to face with the wajinru. The wajinru are shocked by human faces, ‘similar in many ways to our own …The two-legs are our kin’. And later, there is a clear indication that this kinship will lead to unions in the sea.

In Sonia Faruqi’s The Oyster Thief, Izar, the capitalist exploiter of the ocean, now a merman, and Coralline team up and plan to set up a clinic in the mer-world. In Larissa Lai’s Salt Fish Girl, the future is born when Miranda and Evie transform into mermaids. These novels focus on entangled futures, implying that if humanity has to survive, we may need to move beyond our boundaries and become posthuman with other species.

Sigmund Freud spoke of the ‘oceanic feeling’ to describe a sensation of eternity, of a connection with the world. Or perhaps, as these novels suggest, a new kinship that marks a renewed life, race and planet may have to return to the oceans.

The oceanic is where we all are, what is in all of us, or what will be.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

BRS plans grand celebrations for KCR’s 72nd birthday

5 mins ago -

Class 10 students must appear in first board exam: CBSE

41 mins ago -

Revanth Reddy’s sharp ‘U’ turn triggers political debate, leaves Congress leaders miffed

51 mins ago -

CPI’s corporator elected as the first mayor of Kothagudem Municipal Corporation

3 hours ago -

Sultanabad chairman selection postponed

3 hours ago -

Congress infighting erupts at Choutuppal municipal office ahead of chairperson poll

3 hours ago -

Adilabad’s Mukhra (K) residents celebrate KCR birthday on a grand style

3 hours ago -

Jitin Prasada calls AI Summit a ‘Mahakumbh’ for artificial intelligence

3 hours ago