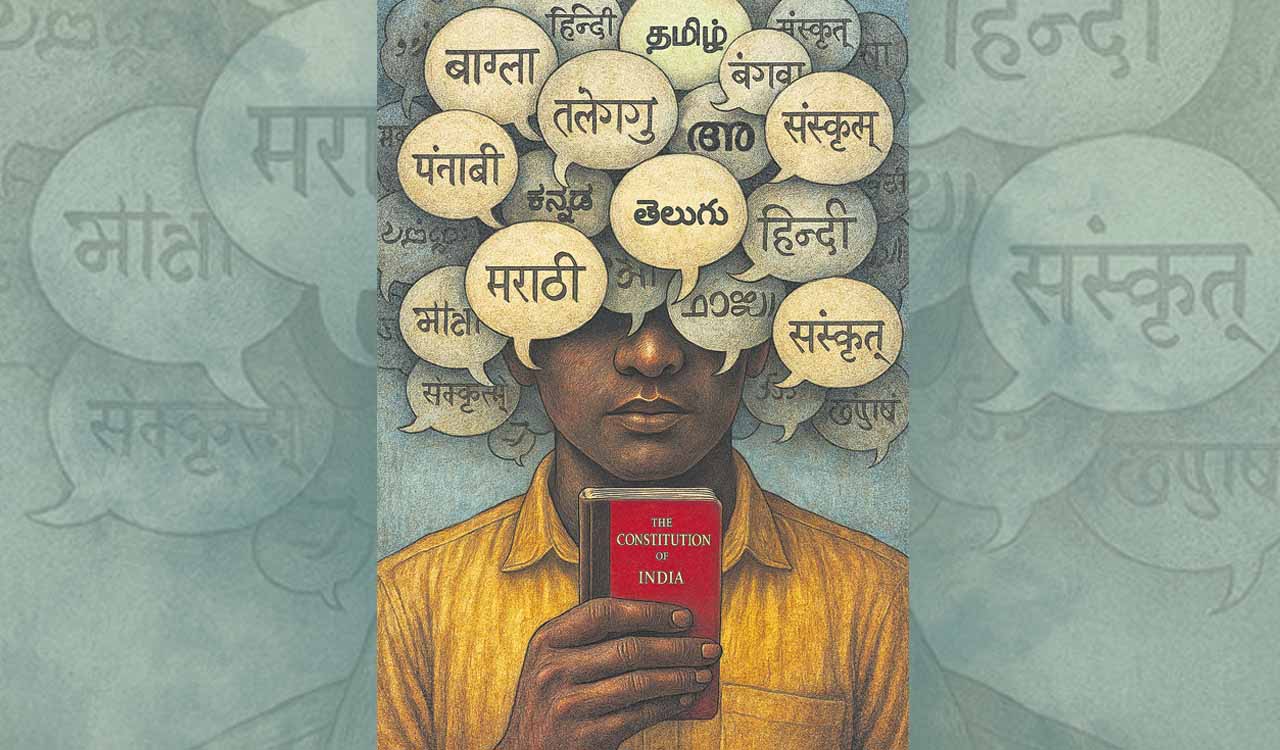

Rewind: Languages and Identities that make India

India’s Constitution prevents imposition of any language; freedom of speech must include the right to speak one’s language — or refuse another

By Prof Dr GB Reddy, Pavan Kasturi

The debate over India’s linguistic identity and a language that serves as a unifying national medium has repeatedly sparked conflict. Recent tensions in different States highlight the connection between language, identity, and political power. History worldwide offers several parallels to this.

Also Read

In Pakistan, the imposition of Urdu on Bengali-speaking East Pakistan culminated in the 1971 Bangladesh Liberation War. Sri Lanka’s Sinhala Only Act, 1956, which marginalised Tamil speakers, led to decades of civil war. Yugoslavia’s collapse was exacerbated by linguistic nationalism, as Serbo-Croatian fractured into politicised variants. Even Canada faced Quebec’s secessionist movements due to Francophone resistance to English dominance.

• India has over 1,600 recorded mother tongues and 22 scheduled languages. The Constitution protects this diversity through Articles 343, 345, and 351, while safeguarding minority rights under Articles 29 and 30

In his Linguistic Survey of India (1928), George Grierson documented the staggering linguistic diversity of undivided India, recording 179 distinct languages and 544 dialects. This complexity was further reflected in the 1951 Census, which reported a total of 845 languages or dialects spoken across the nation. By 1961, the census had recorded 1,652 mother tongues, among which 103 were identified as foreign languages. Hence, the present challenge is existential, forging unity without uniformity, and celebrating linguistic diversity without division.

Pre-Partition (1880s–1940s)

The national language often became a symbol of unity. A common language to connect with the masses and replace the colonial tongue that once connected elites was felt necessary. However, in India, the Hindi-Urdu rivalry catalysed competing language institutions, with Hindi gaining critical momentum after being granted official status alongside Urdu in the Central and United Provinces (now Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh), and Bihar in 1900.

Organisations like the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, founded in 1910, played a significant role in popularising and spreading Hindi. Upon entering the political arena, Mahatma Gandhi shifted the linguistic focus from English to Hindustani. This move was a dual-purpose strategy: to facilitate communication with the vast illiterate population and to forge a common linguistic identity that could help mend the deepening rift between Hindus and Muslims.

• Colonial-era Hindi-Urdu rivalry shaped India’s language politics. Gandhi proposed Hindustani to bridge divides, but Partition disrupted consensus

Gandhi’s Dakshina Bharat Hindi Prachar Sabha (1918) and Rashtra Bhasha Prachar Samiti (1936) targeted southern India. In response, organisations like the Anjuman-e-Taraqqi-e-Urdu emerged as champions of the Urdu language. Yet this institutional push stoked Muslim anxieties over Urdu’s marginalisation.

In response, the Muslim League championed Urdu as a linguistic emblem of Muslim identity. This friction ultimately compelled the Indian National Congress at its 1925 Karachi session to endorse Hindustani — a blended form of Hindi and Urdu as a unifying compromise. Gandhi personally reinforced this via the Hindustani Prachar Sabha (1942).

Constituent Assembly Compromise

Soon after Independence, India’s Constituent Assembly convened in December 1946, pragmatically adopted Hindustani and English as working languages, permitting regional tongues in exceptional cases. Notably, Hindi advocates pushed not for Hindi’s exclusivity but for replacing English with Hindustani alone, as English was seen as a foreign language. However, after the Partition was announced in June 1947, a consensus was reached that Hindustani was not necessary without a united India.

On Sept 14, 1949, Hindi was accepted as the official language by the Constituent Assembly. Interestingly, the “Hindi-wallahs,” as historian Granville Austin called them, pushed further to replace English entirely with Hindi to become India’s sole national language. This faced strong opposition, even from Hindi-speaking members.

In fact, TT Krishnamachari in the Constituent Assembly vehemently argued that

“We disliked the English language in the past. I disliked it because I was forced to learn Shakespeare and Milton, for which I had no taste at all. If we are going to be compelled to learn Hindi, I would perhaps not be able to learn it because of my age, and perhaps I would not be willing to do it because of the amount of constraint you put on me. This kind of intolerance makes us fear that the strong Centre which we need, a strong Centre which is necessary, will also mean the enslavement of people who do not speak the language at the Centre. I would, Sir, convey a warning on behalf of the people of the South for the reason that there are already elements in South India who want separation…, and my honourable friends in UP do not help us in any way by flogging their idea of ‘Hindi Imperialism’ to the maximum extent possible. So, it is up to my friends in Uttar Pradesh to have a whole India; it is up to them to have a Hindi-India. The choice is theirs.”

Few countered that English, already serving as India’s unifying bridge, was the pragmatic choice for national communication as its neutrality made it more acceptable across regions. Finally, the adoption of Article 343 in India’s 1950 Constitution represented a delicate compromise in the language debate, declaring Hindi in the Devanagari script as the official Union language while permitting English to continue for 15 years (1950-1965) as a transitional measure.

• Tamil Nadu’s 1965 anti-Hindi protests turned violent, forcing Parliament to amend the law in 1967 — English was retained indefinitely alongside Hindi

This Munshi-Ayyangar formula cleverly deferred the most contentious decisions to future legislatures. However, the Union is tasked with developing Hindi as a link language by drawing from Hindustani and the Eighth Schedule languages under Article 351. At the same time, Article 345 grants States the freedom to select their official languages, while Article 343 recognises Hindi and English as the Union’s primary means of inter-State communication. Article 347 empowers the President to issue special directives for the recognition of a language spoken by a substantial section of a state’s population, ensuring linguistic minorities are acknowledged.

The language of the higher judiciary is addressed in Article 348, which mandates that all proceedings in the Supreme Court and High Courts, as well as all Acts and Bills, shall be in English. This compulsory use of English was reinforced by the ruling in the Madhu Limaye v Ved Murti (1970) judgment.

Post Constitution

While the formula was not so perfect, the proposed solution struck a delicate balance; it provided essential breathing room, preventing the confusion and resentment that would accompany an abrupt transition. An official language commission (1955) was appointed to check the suitability of Hindi as a national language, but Bengal and Madras opposed it.

In Punjab, the State government’s push for linguistic recognition through the compulsory teaching of Punjabi in Gurmukhi script was perceived by a large Hindi-speaking faction as a threat, sparking a violent ‘Save Hindi Agitation’. In response, the State government enacted the draconian Special Powers (Press) Act, 1956, aiming to curb inflammatory content.

• Globally, similar tensions caused unrest in Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Yugoslavia, and even in Canada

This law was directly challenged by the editors of the Pratap and Vir Arjun newspapers. In a landmark decision, the Supreme Court in Virendra v State of Punjab (1957) upheld the law’s provision for temporary pre-censorship, allowing the government to impose a two-month ban on publications deemed to incite communal violence. The court reasoned this was a ‘reasonable restriction’ on free speech under Article 19(2) of the Constitution, prioritising public order in a volatile linguistic issue.

The linguistic reorganisation of States in 1956 effectively simmered tensions by aligning administrative boundaries with linguistic identities. Jawaharlal Nehru’s 1963 Official Language Act allowed English for government work, Parliament, and courts. However, this was short-lived as the 1965 deadline to drop English neared.

The Madras Agitation (1965) was a massive anti-Hindi protest where students and activists launched strikes, riots, and self-immolations. The violent protests saw railway stations being burned, Hindi signage destroyed, and many deaths. The crisis only abated after the 1967 amendment, which institutionalised bilingual governance, retaining both Hindi and English as official languages indefinitely. There were instances where the Tamil Nadu government attempted to grant pensions to anti-Hindi agitators, which were struck down by the Supreme Court in RR Dalvai v State of Tamil Nadu (1976) as violative of Article 351.

Three-Language Formula

The three-language formula, National Education Policy (1968), saw uneven implementation. Tamil Nadu rejected the Hindi component, while many northern States symbolically substituted Sanskrit as a third language rather than embracing true multilingualism. In contrast, southern States like Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka followed it more sincerely, leading a few children studying even four languages, ie, their mother tongue, regional language, English, and Hindi.

• In 1949, Hindi was made official while English continued as a transitional link under the Munshi-Ayyangar formula. This compromise later became permanent

However, NEP 2020 is a refined formula, requiring students to learn three languages, with at least two being native to India and no language imposed.

Returning to the initial challenge, the solution lies in political wisdom: India needs no unifying language —its strength is its diversity. India’s destiny is that of a vibrant, pluralistic society, one where diversity is not merely tolerated but embraced as its greatest strength. True unity comes not from imposition but from respecting differences.

Further, the search for a national language in India presents a nearly impossible challenge. It requires finding a single language that could simultaneously serve as a unifying symbol for Indian aspirations, bind together an extraordinarily diverse nation with hundreds of languages and cultures, and accomplish all of this without suppressing or coercing any existing linguistic community.

The Constitution forbids language imposition; one could safely say that the freedom of speech includes the right to speak one’s language or refrain from speaking another. Yet, every citizen bears the duty under Article 51A(e) to promote harmony and brotherhood beyond religious, linguistic, and regional divides. A State or citizen can certainly advance their language, but not by forbidding other languages. States committed to preserving their languages can leverage Articles 29-30 for constitutional protection when seeking minority status in other States.

(Prof Dr GB Reddy is Vice Chancellor, NUALS (National University of Advanced Legal Studies), Kochi. Pavan Kasturi is Research Fellow, University College of Law, Osmania University)

Related News

-

Tamil Nadu ready for ‘language war’ if Hindi is forced, says Udhayanidhi Stalin

-

Marathi vs Hindi row turns violent: Student beaten up in Navi Mumbai, One arrested

-

KT Rama Rao’s ‘Deshbhakt’ podcast sparks buzz, clocks 471k views within 24 hours

-

Maharashtra govt withdraws GRs amid political storm over Hindi in schools

-

Iran holds military drills with Russia as US carrier moves closer

22 mins ago -

This is taxpayers’ money: Supreme Court raps freebies culture

58 mins ago -

Hyderabad: Residents oppose Gandhi Sarovar Project over ‘forcible’ land acquisition

1 hour ago -

Australia level series as Indian women slide to 19-run defeat in second T20I

1 hour ago -

Karnataka beat Uttarakhand in semis, to face Jammu and Kashmir in Ranji final

1 hour ago -

Five Osmania varsity players in South Zone squad for Vizzy Trophy

2 hours ago -

Disciplined West Indies bundle out Italy with ease, tops Group C in T20 WC

2 hours ago -

Zimbabwe shock Sri Lanka to enter super eights, African team’s sublime run continues

2 hours ago