Rewind: Dignity, Free Speech, and the Making of Democracy

John Milton’s ‘Areopagitica’, published 380 years ago, was one of the first defences of free speech and quest for truth — its arguments remain valid even today

By Pramod K Nayar

Can one possess dignity as a human if one cannot express one’s views and opinions without fear of being cancelled or worse, incarcerated? The question implies that dignity is automatic to the human, of course. And this is true: dignity has been deemed an integral property of being human, just as the right to one’s views and speaking of them is.

A Brief History of Free Speech

The year 2024 was the 380th anniversary of a text that more or less invented the idea of Free Speech. The poet known today primarily for ‘explaining the ways of God to Man’ in his epic poem titled Paradise Lost, John Milton, published Areopagitica in 1644. Milton was responding to the English Civil War decree that required all writings to be approved before publication.

Milton argued that citizens should not be passive or carry ideas just because ‘his pastor says so, or the Assembly so determines, without knowing other reason’. The citizen must, he said, reason and not be a blind follower of views of either community or leadership. In his memorable words, truth is ‘a streaming fountain; if her waters flow not in a perpetual progression, they sicken into a muddy pool of conformity and tradition’.

Give me the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties – John Milton (1644)

That is, truth should be discussed, contested, argued over, or else it becomes dogma. As he puts it, he cannot accept ‘a fugitive and cloistered virtue, unexercised and unbreathed, that never sallies out and sees her adversary’. This ‘perpetual progression’ of truth demands freedom of expression, and on this ground, Milton opposed the licensing system implemented to curb writing.

In fact, Milton thought that a book was influential beyond its immediate context and may communicate truth to future generations as well: ‘a good book is the precious lifeblood of a master spirit, embalmed and treasured up on purpose for a life beyond life’. Therefore, bans on books were unacceptable: ‘he who destroys a good book, kills reason itself’.

John Stuart Mill’s Essay On Liberty (1859) has never been out of print, for obvious reasons. Mill, like Milton, wanted free debate and discussion: ‘the conflicting doctrines, instead of one being true and the other false, share the truth between them; and the non-conforming opinion is needed to supply the remainder of the truth, of which the received doctrine embodies only a part’.

In short, the different points of view must both be expressible for truth to emerge. What is required is ‘living truth’ rather than ‘dead dogma’. Mill’s argument that ‘the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others’ is still an influential one today when it comes to curbing, say hate speech.

Nearly two hundred years after Milton, the English philosopher John Stuart Mill in Essay on Liberty argued that ‘the conflicting doctrines, instead of one being true and the other false, share the truth between them’

Poems about liberty often included the freedom to express under their broad theme, for example, in Percy Shelley’s ‘Ode to Liberty’. To be fearful of expressing one’s thoughts or views is to lose all freedom, and hence the prospects for both dignity and democracy. The iconic poet of the Harlem Renaissance (the literary and cultural movement among African-Americans in the early 20th century), Langston Hughes, put it pithily in ‘Democracy’:

Democracy will not come

Today, this year

Nor ever

Through compromise and fear.

Through the centuries, these texts have inspired lawyers, philosophers and judges to argue in favour of Free Speech. The American justice, Oliver Wendell Holmes, seems to be echoing Milton and Mill when he pronounced: ‘the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas — that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out’. Truth, therefore, emerges in the contest of ideas — which requires Free Speech.

Holmes would go so far as to say, echoing the philosopher Voltaire, that we should actively enable those with ideas contrary to our own, to speak freely. Referring to the American Constitution, Holmes said: ‘[I]f there is any principle of the Constitution that more imperatively calls for attachment than any other it is the principle of free thought — not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought that we hate’.

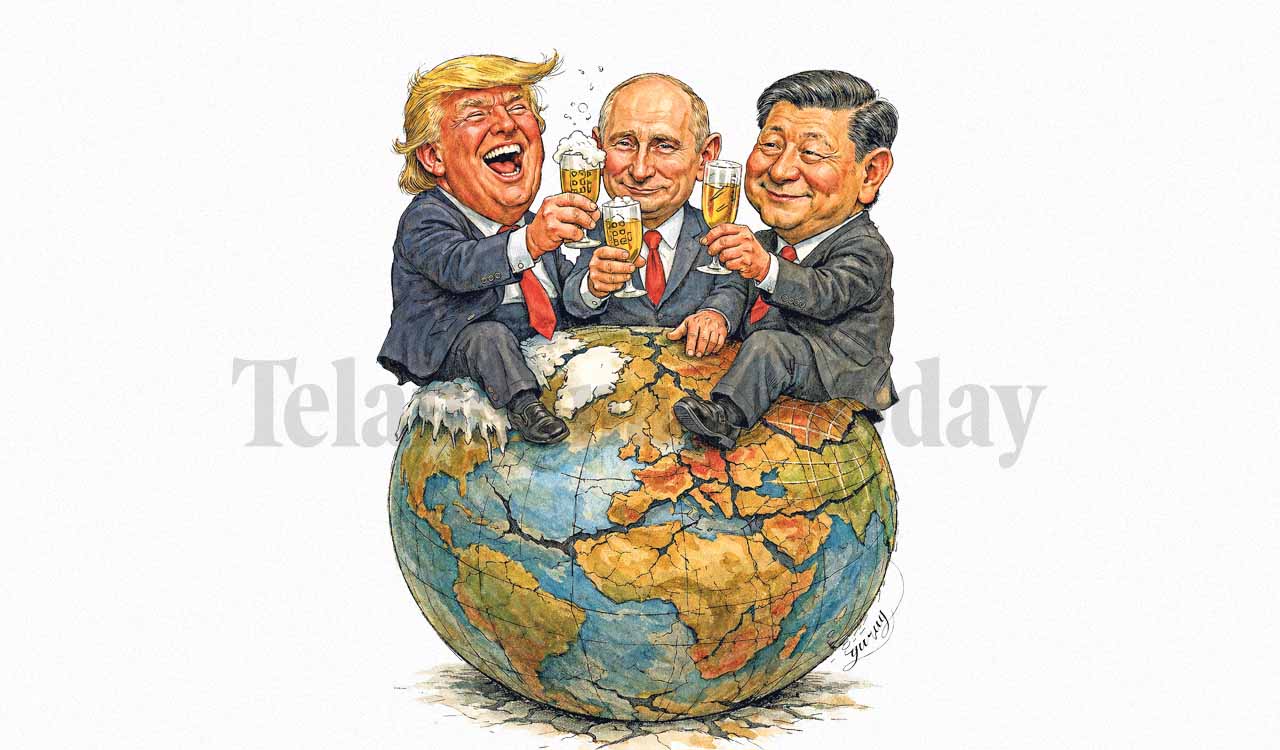

It is likely, as the French philosopher Jacques Derrida pointed out in his book Rogues: Two Essays on Reason that in the processes of democracy, we may vote into power through the exercise of democratic freedoms, to the demagogues:

must a democracy leave free and in a position to exercise power those who risk mounting an assault on democratic freedoms and putting an end to democratic freedom in the name of democracy ?

This is the irreducible pathless path of democracy itself: that we elect the undemocratic.

A Brief History of Dignity

Dignity has been enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948). Its Preamble says in its very opening:

Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world…

Later it adds:

Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom…

The German Constitution’s Article 1 opens with the declaration: ‘human dignity is inviolable’. The European Court of Human Rights claims that dignity is ‘the very essence of the Convention’. In the Charter of the European Union it appears right away, in Article 1. Even regional human rights pacts mention dignity in their preambles, as do the American, Arab, and African conventions or charters. The Helsinki Accords (1975) claim that human rights ‘derive from the inherent dignity of the human person’.

Dignity is not bestowed: it is inherent to every living person simply by virtue of being human. Democracy hinges on recognising the individual’s dignity, and free speech ensures this dignity

These conventions and charters assume that dignity is a quality attributed to every individual and which every public authority has to respect. In terms of the philosophical foundations that seek normative modes of defining human dignity, constitutional scholar Marcus Düwell writes:

The scope of ascription of human dignity is universal in the sense that it applies to all human beings, it is egalitarian insofar as each human being is equal with regard to his dignity and references to human dignity are justifying duties towards others that have the form of categorical obligations.

Josiah Ober, the Stanford political scientist, defines it thus:

Dignity can be defined as non-humiliation and non-infantilization. We suffer indignity … when our public presence goes unacknowledged, when we cringe before the powerful, when we are unduly subject to the paternalistic will of others and when we are denied the opportunity to employ our reason and voice in making choices that affect us.

The Dignity in Speech

Individual speech is located within the remit of individual freedoms across the world. This is so because, if we accept that the human is a social animal, and communicating with fellow humans is intrinsic to her/his well-being, then it follows that her/his dignity hinges on being able to share views and opinions that define her/him.

It is tricky in cases where free speech is protected by law but dignity is not, or vice versa. In such cases, Dieter Grimm, constitutional scholar, argues that ‘dignity serves as a remedy of last resort to either permit or forbid speech, depending on where such a serious lack of positive recognition exists that it affects dignity’.

If dignity is central to being human, as is speech, and democracy is the form of government that is most suitable for the protection of an individual’s dignity, then it follows that free speech that protects dignity is linked to democracy as well. There is, of course, no democracy without free speech, and so, democratic rights of free speech ensure an individual’s dignity.

To be vulnerable in speaking is to be vulnerable in one’s core dignity. Those who have their dignity taken away are also, conversely, rendered speechless.

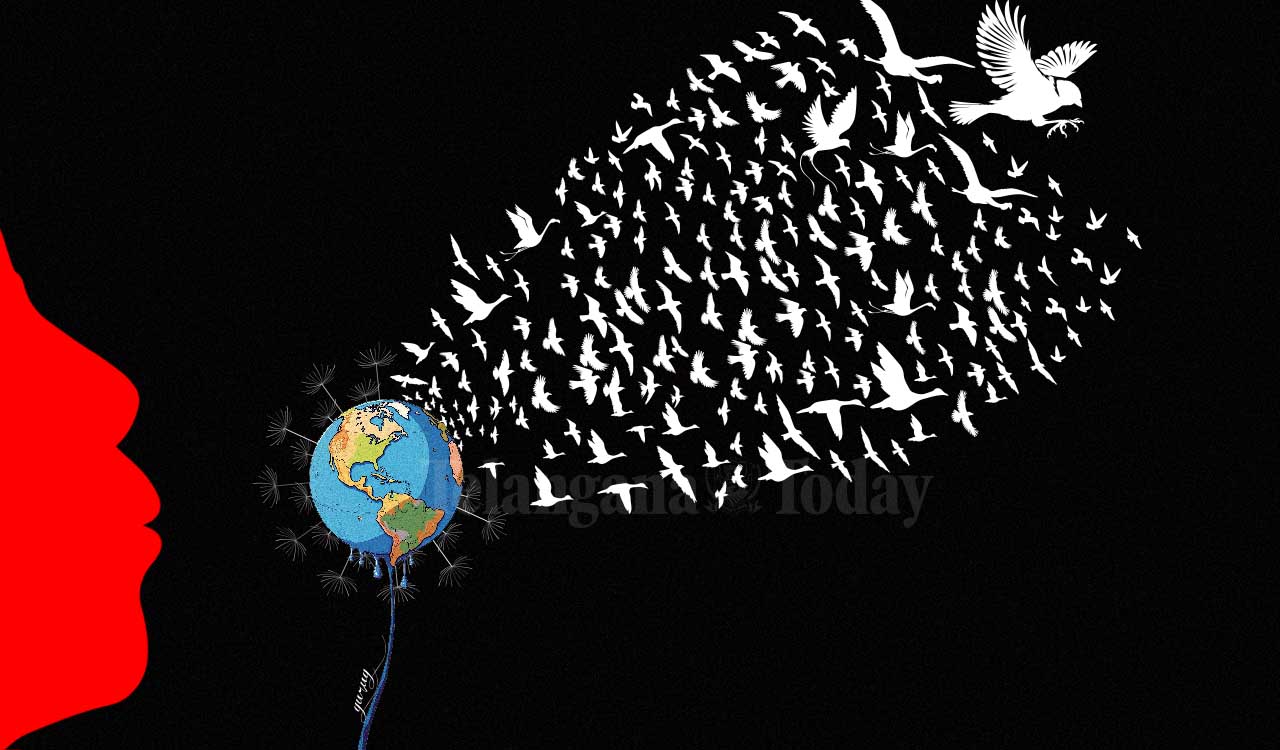

Conversely, to be penalised for speaking is an affront to one’s dignity. As the poet Maya Angelou in her powerfully allegorical ‘Caged Bird’ would say, while the bird in the cage continues to sing, its song is a yearning for freedom:

The caged bird sings

with a fearful trill

of things unknown

but longed for still

and his tune is heard

on the distant hill

for the caged bird

sings of freedom.

The Indignity in Speech

However, as most legal systems see it, limitations placed on free speech can be justified if such speech adversely impacts the dignity of another. Thus, humiliating speech cannot be justified in the name of free speech precisely because to humiliate another person means to erode that person’s dignity. Hence, the framing of defamation laws which aim to ensure the essential dignity and worth of every human being. Such defences against speech that negates the dignity of individuals have been incorporated across the world.

The University Grants Commission, to take just one instance, states in its 2018 Regulations under the section ‘Code of Professional Ethics’ that teachers

Speak respectfully of other teachers and render assistance for professional betterment;

Refrain from making unsubstantiated allegations against colleagues to higher authorities

Exemplified in the UGC Code is the assumption that a certain kind of speech will create a climate in which a certain kind of action becomes possible that would then be a threat to those targeted in such speeches. An extreme example would be Holocaust denial. Speech that denies the Holocaust creates conditions in which anti-Semitism may return and thus pose a threat to the Jews.

Hate speech is a true test: should it be permitted because we believe every person has the right to voice her/his opinion even if the opinion is derogatory or likely to cause harm to others?

In Germany, Canada, the European Court of Human Rights, therefore, treated instances of Holocaust denial as a punishable offence. As one Chief Justice of Canada, Brian Dickson, wrote:

A person’s sense of human dignity and belonging to the community at large is closely linked to the concern and respect accorded to the group to which he or she belongs . . . The derision, hostility and abuse encouraged by hate propaganda therefore have a severely negative impact on the individual’s sense of self-worth and acceptance.

This does not, given the current conditions, preclude the fact that the Israeli state can be criticised for its genocidal acts in Palestine without such criticism being labelled ‘anti-Semitic’. Neither does the explaining away of Hamas’ attack as an inevitable moment in a long history of violence of settler-colonial regions become anti-Semitic.

The terms in which a moral condemnation of all forms of violence, by all sides ‘big’ and ‘small’, state and non-state actors, is made, and such a condemnation that is attentive to histories of injustice are, therefore, crucial to critical debate and its core: free speech.

A controversial prohibition on free speech has been the legislations on obscenity. Courts conceded that, unlike hate speech which usually has a specific target group, pornography does not. The only exception to the Freedom of Speech concept and practice, judges across the world agree, is hate speech.

Finally, the Canadian court in its decision in R v Butler (1992) argued that obscenity ‘degrades and dehumanizes’ and, therefore, is analogous to hate propaganda. It pronounced:

Among other things, degrading or dehumanizing materials place women (and sometimes men) in positions of subordination, servile submission or humiliation. They run against the principles of equality and dignity of all human beings. In the appreciation of whether material is degrading or dehumanizing, the appearance of consent is not necessarily determinative. Consent cannot save materials that otherwise contain degrading or dehumanizing scenes. Sometimes the very appearance of consent makes the depicted acts even more degrading or dehumanizing. obscene materials ‘run against the principles of equality and dignity of all human beings.’

The ruling clearly calls for dignity as a cornerstone of the legal apparatus, and in the process makes a strong case for treating human dignity and its enunciative embodiment — free speech — as integral to the person itself.

To speak and to listen is the marker of civilisation itself. The poet Adrienne Rich concludes her famous poem, ‘What Kinds of Times are These’ with the emphasis on speaking and empathetic listening. The point is not about trees, but the right to and necessity of, talking about them.

so why do I tell you anything?

Because you still listen, because in times like these

to have you listen at all, it’s necessary

to talk about trees.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Couple elected as chairperson and vice-chairperson of Nirmal Municipality

2 hours ago -

Telangana municipal polls: BRS pockets 18 municipalities

2 hours ago -

BJP draws sharp criticism for meeting Congress leaders in Hyderabad

2 hours ago -

Inorbit Mall Cyberabad hosts Valentine specials, interactive games and live performances

2 hours ago -

Jangaon chairperson election postponed amid high drama

2 hours ago -

Editorial: Showcasing India’s tech prowess

3 hours ago -

Health Minister orders suspension of absent Jogipet doctors

3 hours ago -

Opinion: India’s new labour codes prioritise capital over labour

3 hours ago