Rewind: Never Let Me Go — The clones we create

As it turns 20, Ishiguro’s ‘Never Let Me Go’ echoes Shelley: Are we not responsible for the clones, the creatures we design with the will to serve humans?

By Pramod K Nayar

Clone Robotics announced to much fanfare the arrival of Protoclone. Made of Myofiber, the company’s own invention, and touted as the ‘only artificial muscle in the world capable of achieving such a combination of weight, power density, speed, force-to-weight, and energy efficiency’, the Protoclone mimics the human. And what’s more, ‘you can speak to the clone in English’, declares Clone Robotics proudly. ‘Do it yourself once, the clone will do it forever’, it says. Welcome to the new age service providers. It is at once a proto-type and a clone.

Also Read

But this seems rather tame, even by the standards of the AI age when debates rage as to whether Artificial Beings (ABs) deserve welfare and voting rights (they do not eat so they are not consumers in this sense at least). Anticipating the ethical and moral debates around the role of ABs in human lives, homes and societies, designed to serve humanity, is a novel celebrating its 20th anniversary in 2025. Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, also a hugely successful film, threw up more questions than it answered, but foregrounded for us the value systems that humanity continues to espouse when it comes to the servitor class.

Never Let Me Go (2005) deals with the life of a group of clones studying at a school, Hailsham, and is set some time in future London. The clones are created, if that is the word, so that when the time comes, their internal organs can be harvested to aid humans with terminal conditions. The harvesting is termed ‘donations’ and usually, after the fourth donation, the clones die. The tale, narrated from the point of view of one of the clones, Kathy H, ponders multiple questions, often raised by the clones themselves, over the ethics of cloning such beings with the exclusive intent of making use of their bodies for human purposes.

• Debates rage as to whether Artificial Beings like Sophie deserve rights of any kind, especially when they function as companions, assistants and even servants to humanity

Living Cadavers

In Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake (2004), special animals are bred with extra kidneys and livers which could then be harvested. In Ishiguro’s novel, these special creatures are human clones.

The clones when they start their involuntary ‘donations’, become ‘living cadavers’ (Chris Hables Gray’s term). While they do possess sentience, intellect, emotions and all the drives and instincts of humans, they merely exist to provide organs. They are bodies and lives that may be terminated at human will. Beyond their role of donors, they do not count:

Their [the humans’] overwhelming concern was that their own children, their spouses, their parents, their friends, did not die from cancer, motor neurone disease, heart disease. So for a long time … people did their best not to think about you. And if they did, they tried to convince themselves you weren ’t really like us.

One can then even think of them as living storehouses wherein, without refrigeration, meat and organs are stored for future use. The organs are of course commodities, being harnessed from this storehouse as and when humanity needs them. So a posthuman store wherein one can pick up, buy and use key organs to protect humanity.

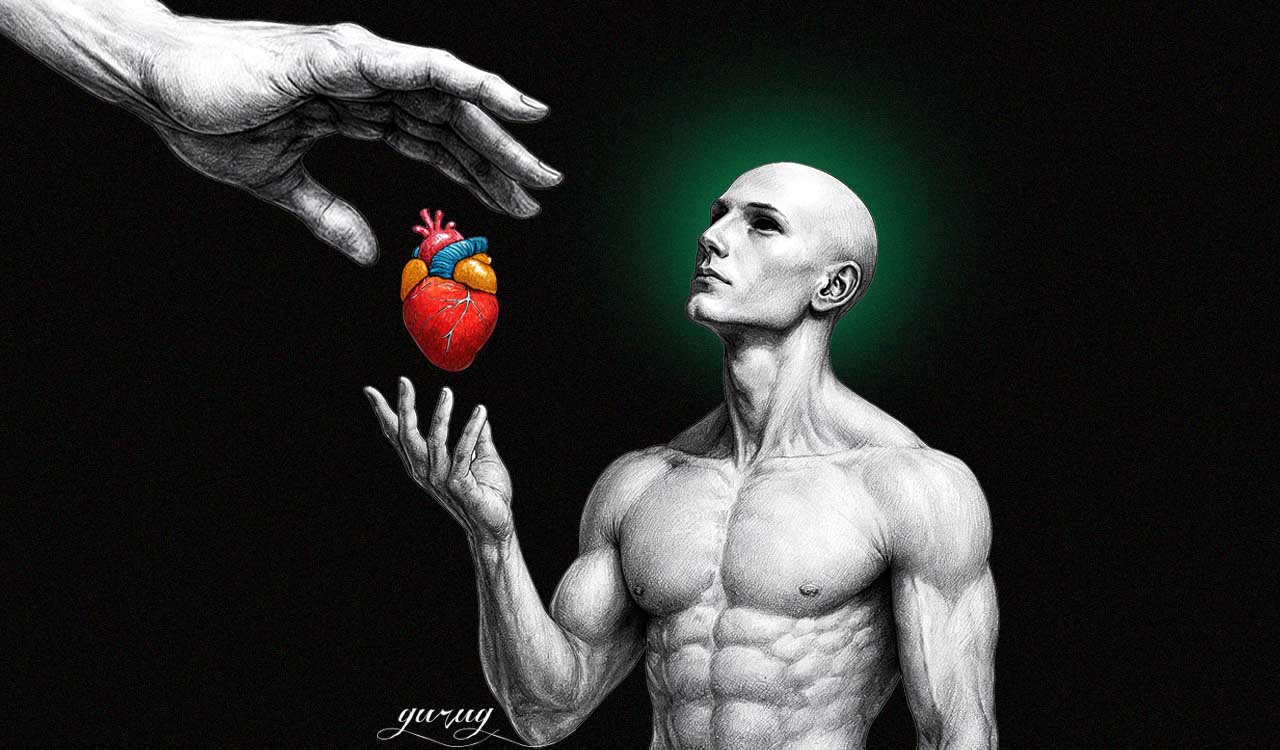

Yet, Ishiguro complicates such a simplistic reading. Xenotransplantation – transplantation of organs from other living beings – is at the heart of the tale. And yet are these foreign organs (xeno means foreign)? The clones are themselves made from humans, and their organs go back into humans. In other words, there exists an organ cycle that blurs the borders between origin (humans as origins for clones, clones as the origins of the organs) and destination (the clones as the destination, or products, of human cloning, the humans as the destination of clone organs). The transplantation undermines the clone/human, foreign/self-distinction.

In his tract on transplantation, the philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, who received a new heart, ponders whether his original heart was really his, because it betrayed him. ‘If my heart was giving up and going to drop me, to what degree was it an organ of “mine,” my “own”?’, he asks. Consequently, he asks whether the heart he has received and which his body has accepted has become his own. And, since the heart is stereotyped as the seat of emotions, he wonders whose emotions he felt when his heart behaved like a stranger and now when he has someone else’s heart.

In the same vein, Ishiguro asks: what separates the humans from clones if the latter are our progeny and products and their organs keep us alive? And why would they be second-class citizens when they are sentient human creations?

• If clones and Artificial Beings are our progeny, even if they have been created in unconventional ways, then what makes them lesser persons or non-persons?

A New Servitor Class?

Are clones and ABs another servitor class, and if so, are we looking at a new brand of slavery? Ishiguro would return to this question in his later work, Klara and the Sun, where Klara is an Artificial Friend who is to be a companion to a sick child. In Never Let Me Go, the servitor-class is derived from the humans and are thus, in effect, a variant of the human whom we, humanity, have consigned to be our servants.

The debate about this class is mired in the question of origins. The clones are not robots. The clones themselves seek their origins, or ‘possibles’:

The basic idea behind the possibles theory was simple, and didn’t provoke much dispute. It went something like this. Since each of us was copied at some point from a normal person, there must be, for each of us, somewhere out there, a model getting on with his or her life. This meant, at least in theory, you’d be able to find the person you were modelled from.

And here, with the knowledge of their future as living cadavers, Ruth pronounces their less-than-decent origins:

We’re modelled from trash. Junkies, prostitutes, winos, tramps. Convicts, maybe, just so long as they aren’t psychos. That’s what we come from. We all know it, so why don’t we say it? A woman like that? Come on. Yeah, right, Tommy. A bit of fun. Let’s have a bit of fun pretending… If you want to look for possibles, if you want to do it properly, then you look in the gutter. You look in rubbish bins. Look down the toilet, that’s where you’ll find where we all came from.

Ishiguro is drawing parallels with slavery: with how some classes and races of humans were deemed to be closer to animals and, therefore, subhuman, like the clones who originated in Ruth’s interpretation from ‘trash’.

The debate about origins is not simply that. It also raises questions as to the ethics of creating a class of beings who exist to serve humanity. Ishiguro here and Klara, however, does not just raise this ethical question. Unlike slaves, who were made to serve humans against their will, clones and ABs are designed with the will to serve humans. Then, if we have created ABs who are meant to serve humans, whose very capabilities are directed at serving humans, then principles of justice demand that they be allowed to fulfil their capabilities. If the AB or the clone has to grow and reach the peak of her or his capabilities then society must allow them the rightful freedom to serve humans.

As the philosopher Stephen Petersen making a case for ‘engineered robot servitude’ puts it:

It seems possible to design robots from scratch so that they want to serve us in more or less particular ways. In such cases the robots are not slaves, since they are not working against their will…

That is, if it is designed that the clones and ABs are meant to serve humanity, then should we prevent them from reaching their full potential in doing so? Of course, this question follows the resolution of the larger problem, as to whether we ought to design such beings at all.

• Ishiguro in Never Let Me Go and Klara and the Sun calls attention to the creation of new forms of slavery, of servitude, where robot sapiens are built to serve humanity

Those With Souls Have Rights

At one point in the novel, Ruth states: ‘I was pretty much ready when I became a donor. It felt right. After all, it’s what we’re supposed to be doing, isn’t it?’ The clones are predestined to donate their organs and then die. They have no self-determined purpose, they cannot choose their fate. Ishiguro is, in fact, directing our attention to a key question: do all sentient creatures, including clones and artificial beings, have the right to choose their life goals, the plot of their lives?

The clones are told in Hailsham:

Your lives are set out for you. You’ll become adults, then before you’re old, before you’re even middle-aged, you’ll start to donate your vital organs. That’s what each of you was created to do … You were brought into this world for a purpose, and your futures, all of them, have been decided..

This is acculturation, a pedagogic mode of convincing the clones that their life choices have been made for them. And yet, this acculturation is itself double-edged, as a teacher tells them in Hailsham:

We demonstrated to the world that if students were reared in humane, cultivated environments, it was possible for them to grow to be as sensitive and intelligent as any ordinary human being. Before that, all clones — or students, as we preferred to call you — existed only to supply medical science.

Ishiguro’s larger query is: do we humans have the right to determine the life plots of sentient creatures? If so, how is this different from slavery where the fates of millions of Africans were determined by a handful of plantation owners and industrialists?

The issue of rights is complicated when Ishiguro moves beyond mere sentience to speak in terms of souls. We are told that on occasion, the artwork of students is taken away and put in a gallery so that it can be proved that clones who possess artistic abilities also possess souls: ‘we did it to prove you had souls at all’, as one teacher puts it. But does this mean that those beings in possession of souls are being denied rights and is art a function and manifestation of the soul? (In an age when AI generates art, this can be a further trajectory to think along)

But sentient creatures observe themselves, possess self-reflexivity. In Never Let Me Go, we realise that the clones are aware of their slowly diminishing lives:

But Tommy would have known I had nothing to back up my words. He’d have known, too, he was raising questions to which even the doctors had no certain answers. You’ll have heard the same talk. How maybe, after the fourth donation, even if you’ve technically completed, you’re still conscious in some sort of way; how then you find there are more donations, plenty of them, on the other side of that line … how there’s nothing to do except watch your remaining donations until they switch you off.

Now, if we assume that sentience plus emotions makes us human, the clones and ABs do show emotions. It could be argued that the latter are programmed to possess and express certain emotions. But we recognise that human emotions are themselves the product of cultural training: we do not express all that we feel, we only express what is socially acceptable. So then, how is this emotional intelligence training different from algorithmically programmed emotions, asks Ishiguro.

The question of justice and rights can no longer be restricted to humans if we merely reproduce ourselves as clones or ABs because those too are human progeny, ‘born’ with the same feelings and intellectual abilities as other humans and designed to fit our households and hearts.

It is appropriate that it is in the 20th anniversary year of Never Let Me Go that Guillermo del Toro returned to the novel that began the debate over the responsibility of the creator towards the created, the philosophical and ontological status of an artificial being and the relationship between the human and quasi-human (or allo-person): Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818).

Never Let Me echoes the thorny issue the creature raises in Shelley: ‘I ought to be thy Adam, but I am rather the fallen angel, whom thou drivest from joy’. Ishiguro wonders, are we not responsible for the clones, the creatures we design and create?

Kazuo Ishiguro cautions us that humanity owes something to those it creates. Even if those we create are, as Mary Shelley called her book, our ‘hideous progeny’.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

Tirumala laddu row: SC refuses to entertain plea for action against those spreading ‘misinformation’

3 mins ago -

No shortage: Panic bookings delay LPG deliveries, say Hyderabad LPG Agencies

7 mins ago -

SC takes suo motu cognisance of illegal sand mining in National Chambal Sanctuary

11 mins ago -

Panic buying cripples LPG booking system in Telangana

23 mins ago -

LS adjourned till 12 noon amid Oppn protests over LPG price hike

23 mins ago -

Rashmika Mandana warns legal action after private audio leak

28 mins ago -

Aditya Dhar reveals the biggest lesson he learned this year: Never loose belief

33 mins ago -

APGENCO hits record 6,160 MW thermal power generation, Andhra CM hails milestone

34 mins ago