Rewind: Reviving temple dance — Ranganatha Swamy, Ramappa and beyond

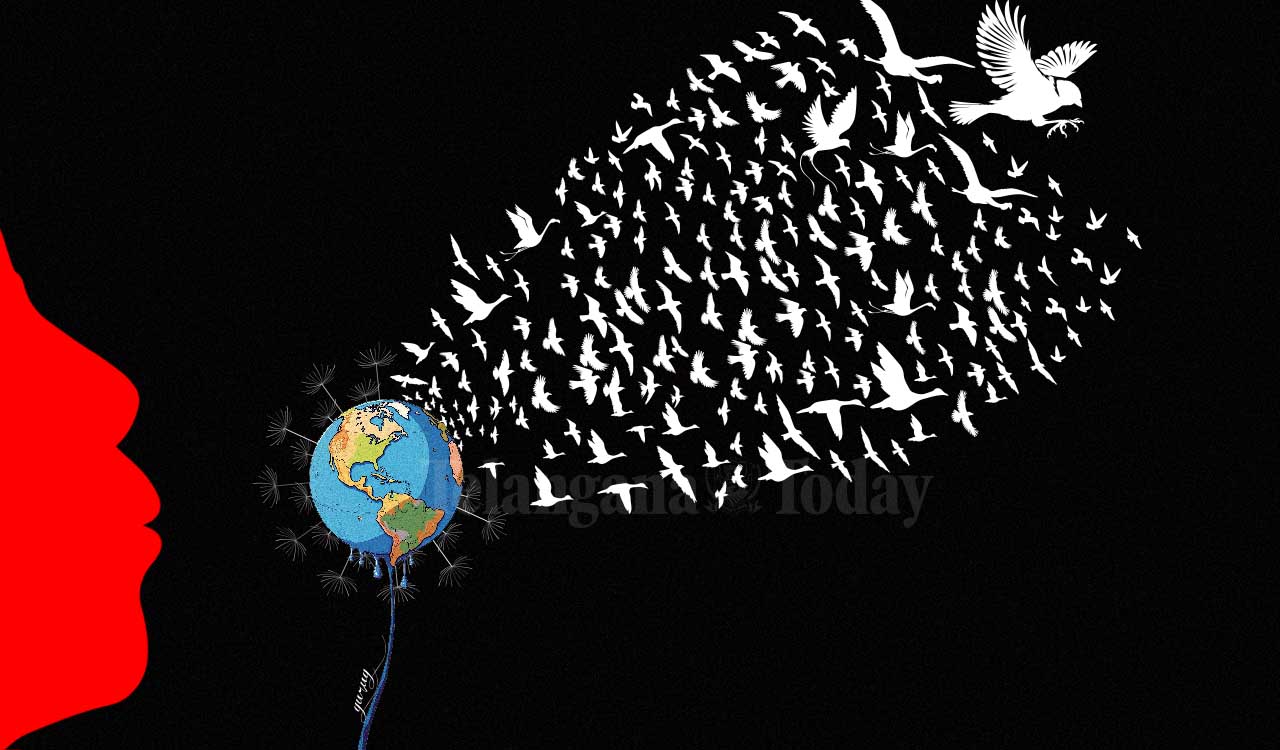

Torn from worship and reduced to spectacle, temple dance lost its sanctity to colonialism, reform, and exploitation. Beginning from Hyderabad’s Sri Ranganatha Swamy Temple, Swapnasundari continues her relentless journey to revive the art and restore it to sacred ritual

For centuries, temple dance was an offering to the divine — until sexual exploitation, colonialism, and social reform erased it from worship. In 1996, the 400-year-old Ranganatha Swamy Temple at Rang Bagh in Nanakramguda, Hyderabad, introduced dance in its unblemished form during live worship, becoming the only temple in India to reinstate this sacred practice — thanks to temple-dancer Swapnasundari.

Since then, ritual dance has continued here under special provisions. She has been dancing at Sri Ranganatha Swamy Temple for 28 years during Brahmotsavam and Kalayanotsavam (special occasions). The dance starts right in front of the deity, and people are allowed to watch and be a part of the entire ritual.

Also Read

More than reviving temple dance, the Padma Bhushan awardee is now reclaiming its history, confronting distortions and exploitation, and restoring dignity to the women who once embodied this art.

“The act of offering dance and music rituals in a temple is not for general entertainment. It is mandated in the Agama Shastras, which govern worship in all temples. Some temples tried to emulate the initiative of Rang Bagh temple. Still, they could not sustain it due to the challenges involved,” says Swapna, the eminent exponent of Agama Bharatam, Kuchipudi, Vilasini Natyam and Bharatanatyam.

Agama Shastras are ancient manuals on temples that prescribe guidelines for temple construction, site selection, image formation, installation, and infusion of ‘Pranic energy’ into the main idol. Temples follow the Agamic tradition of worship, which mandates the incorporation of dance and music in important sacred rituals. It also details how and when dance and music should be offered during worship.

“So terrible was the treatment of hereditary temple dancers in the years leading up to India’s independence — that in Telugu-speaking areas, their own community distanced itself from temple service because of merciless financial and sexual exploitation”

Agama Bharatam, formulated by Swapna, is the dance and music system of India’s temples, as prescribed in Agama Shastra. This, however, should not be interpreted as advocating, reviving and carrying forward the now defunct Devadasi tradition, she clarifies.

Swapna has been researching and performing temple dance for nearly three decades and categorically says that performing a Bharatanatyam, Kuchipudi or Manipuri dance as we see it today in a temple is not the real temple dance.

“When people say we danced in a temple, usually they mean that the temple served as a backdrop or a location to perform dances with religious/mythological themes. These performances follow regional dance traditions which have been passed on by gurus who specialise in those dance traditions,” she says.

Bharatanatyam, Odissi, Manipuri, Kuchipudi, Kathak and others are such regional expressions of dance that have artistic connections with the principles of Bharata’s Natya Shastra. However, in their present form, she says “they do not align in toto with the specific and exact requirements of temple dance or temple music as prescribed by the Agamas.”

Decline of Temple dance

The gradual decline of the temple ecosystem paved the way for the Madras Devadasis (Prevention of Dedication) Act, 1947, enacted by the British colonial administration. This law banned the dedication of women to temples and outlawed their public performances in the Madras Presidency. To be sure, while the British ruled India for 200 years, the erosion of Bharatam had begun much before their arrival.

In North India, Tawaifs, or non-temple dancers, thrived during and after the Mughal era. As their influence grew, girls from ‘respectable’ (read: wealthy, so-called upper-caste) families were discouraged from learning fine arts, as dance became associated with courtesans. “It was quite common for an Englishman to take a Tawaif as a Bibi — a term for a dancing girl in a conjugal relationship with a British officer, though it was never a legally valid marriage.”

“Like India’s Constitution, which has accommodated amendments and evolved over decades, so too must Agama Shastras be revisited and expunged of any feature which creates scope for exploitation of women, for dance and music to return to worship in their purest form”

The rise of European power further hastened Bharatam’s decline, distancing dance from its sacred roots. In the British-ruled Madras Presidency (which included much of undivided Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and parts of Karnataka, Kerala, and Odisha), many singer-dancers hailed from families which had links to temple worship. But the steps, movements and expressions held little significance for the colonisers, who summoned these artists only to entertain British officers in camps, hunting expeditions and parties.

“The earlier connections between worship and dance were already at a low point. These decontextualised performances added to the view that Indian dance is merely entertainment. The Sanskrit term Natya became ‘Nautch’ and its performers were labelled Nautch-girls and Bayaderes,” says Swapna, tracing the decline.

The Devadasi Act was intended to prevent sexual exploitation of women, but it failed to provide the Devadasi community with viable alternatives for sustenance. This sealed the fate of temple-ritual dance altogether.

The term Devadasi translates to “one who serves God”. In temple worship, the Dasi was not viewed as a servant in the conventional sense but was a respected member of the temple staff, offering service to the deity through dance and music. Devadasis were self-sufficient and highly qualified women. Vidyasundari Bengaluru Nagarathnamma was an outstanding example of this tradition.

However, unlike other temple functionaries — such as archakas (priests), musicians and singers — Devadasis were denied the right to marry and raise families. This clause made them vulnerable to emotional and physical exploitation. “So terrible was their treatment — especially in the years leading up to India’s independence — that the community itself took pledges to stop dedicating women to temples because they were being mercilessly exploited,” she says.

When temples shut their doors on Devadasis, there was no effort to retain dance as an integral part of worship because no other class of women were permitted to dance and sing in public, even if they were trained in these, she points out. The true Agamic dances also vanished with this. And this loss did not happen overnight in the 1930s or 1940s.

“The decay had started much earlier, even within the temple’s ecosystem itself. That is why, when people of my generation wanted to rediscover the authentic Devadasi dance, we couldn’t. Not just me, those who entered the field of performing arts even 100 years before did not have access to the practical study of the original Agamic dance. ”

Her search was made even harder by the scarcity of texts and literature. The only sources of information were notes held by archakas or their oral recollections.

Vilasini Natyam to Agama Bharatam

In the early 90s, Swapna was invited to Eluru in Andhra Pradesh for a Kuchipudi performance. In a subsequent function, an elderly artiste, Maddula Lakshmi Narayana, demonstrated her art. It was an informal yet deeply captivating performance which impacted Swapna. “Her memory was phenomenal even though she had stopped dancing more than 40 years ago due to the anti-Devadasi Act,” she recalls.

Her initial study under the tutelage of Maddula Lakshmi and her eagerness to learn more led her to many such artistes — all from Telugu-speaking regions, whose predecessors had worked in temples.

She was encouraged and supported by Badri Vishal Pitti, the chief trustee of the Ranganath Swamy Temple, and his family. “They took the bold step by inviting me to incorporate ancient worship dances in the temple’s utsavas (festivals).”

Vilasini Natyam is the name given by Swapna to the Bharatam of the Telugu temple and court dances. A large team of hereditary dance informants of Telugu-speaking regions, historians, linguists and scholars also supported this name. The term Vilasini means one who revels, one who enjoys herself. Eminent Telugu researcher and historian Dr Arudra had initially suggested the name to her since it appears in inscriptions referring to temple dancers.

Explaining the choice of the name, she says, it’s just like Mohiniyattam, which evolved in the courts of Kerala and incorporated elements of temple dance traditions. Dasiattam was later renamed Bharatanatyam, as the earlier name had lost social respectability in the Tamilian South. Similarly, Vilasini Natyam has been involved in restoring the dance traditions of Telugu female hereditary dancers.

Agama Bharatam

Swapna has gone far beyond Vilasini Natyam. She has pushed the frontiers by studying the Agama Shastras and many treatises related to Bharatam to create a corpus of dance compositions which incorporate the principles of Bharatam as defined in the Agama Shastras.

“It is necessary to further systematise and popularise the entirety of temple dance and music as per the Agamic mandate and create awareness about it. It is my dream to extend its reach to diverse linguistic and cultural groups,” she says

Restoring temple dance in its comprehensive form on a large scale and as a part of worship requires legal, religious and cultural reforms. While legal reforms matter, it is equally crucial for major religious institutions to take significant steps to breathe life into the neglected tradition of Agamic dance.

“Just as the Constitution of India has evolved and developed, so too must the Agama Shastras. Exploitative clauses, if any, must be removed so that Sangeetam (song, instrumental music and dance) in its pure form returns to worship. These arts were once elevated to the stature of the Gandharva Veda, the fifth Veda. That sacred essence has been lost,” she says.

Swapna remains committed and is willing to walk this path alone, but she also welcomes collaboration. “Otherwise, we will lose a vital part of our intangible cultural heritage,” she says.

Worship and Agama Shastra

(By CS Rangarajan, Head Priest, Chilkur Balaji Temple, Hyderabad)

Agama Shastra is divided into the following four:

- Jnyana (Jnyana Pada): This includes the philosophical and spiritual knowledge. Here, Nrittam or Natyam is mentioned as a manifestation of spiritual knowledge using gestures and performed to make the audience understand the philosophy and spirituality involved in a particular religion. It is performed during festival occasions and a number of devotees visit the temple during that time.

- Yoga (Yoga Pada): Describes the mental and physical practices. In this, Nrittam or Natyam is mentioned as a kind of yoga practice, which leads to unification and higher consciousness.

- Kriya (Kriya Pada): Ways of worship and temple construction. Here, Nritya Mandapam or Natya Mandapam is an integral part of the temple construction in certain regions and traditions. Nrittam or Natyam is also mentioned as a service or offering (upachara).

- Charya (Charya Pada): Rituals or rules to perform worship. This mentions when Nrittam should be performed, where it should be performed, and how long it should be performed.

Significance of dance during Utsava (temple festivals )

As a part of utsava, Nrittam is employed as a tool to convey philosophical, spiritual and moral values to the devotees or followers.

Stories from mythology are also enacted along with relevant music, which gives a better understanding of the presiding deity in the temple. The concepts of Vedas and Upanishads are also enacted with proper musical rendering, which serves as an audio-visual presentation of the texts that can be understood by all classes of people.

In Agama Shastra, many ways of worship are explained. In one particular way of worship, god is treated as a king. During the invocations, a promise is made: nrithya geetha yutham vadyam nithyam athra vivardhataam. (Let the song, dance and music coupled with instruments keep increasing by the day).

These services or luxuries offered to the god are called Rajopachara (Raja meaning king and upachara is service/ luxury). There are various kinds of Rajopachara, like holding an umbrella and showing a mirror. Here, dance and music have an important role.

The offering is narrated as:

- Geetham Sushravayam Avadharayami (I offer to God, this music/song to his ears to please him)

- Vadyam Avadharayami (I offer playing of the instrument to Lord for his pleasure)

- Nrityam Avadharaya (I offer this visual presentation of dance to the Lord)

(With inputs from Lakshmi Karthik, Member of the International Dance Council, UNESCO)

Related News

-

Couple elected as chairperson and vice-chairperson of Nirmal Municipality

3 hours ago -

Telangana municipal polls: BRS pockets 18 municipalities

3 hours ago -

BJP draws sharp criticism for meeting Congress leaders in Hyderabad

3 hours ago -

Inorbit Mall Cyberabad hosts Valentine specials, interactive games and live performances

3 hours ago -

Jangaon chairperson election postponed amid high drama

4 hours ago -

Editorial: Showcasing India’s tech prowess

4 hours ago -

Health Minister orders suspension of absent Jogipet doctors

4 hours ago -

Opinion: India’s new labour codes prioritise capital over labour

4 hours ago