Opinion: Politics of Eviction and minorities

The evictions and targeted policing of Bengali-speaking Muslim workers expose a systemic assault on India’s secular and democratic principles

By Geetartha Pathak

India’s Constitution, a beacon of secularism and equality, declares the nation a “sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic,” enshrining fundamental rights such as equality before the law (Article 14), non-discrimination (Article 15), and freedom of religion (Article 25).

These principles align with international humanitarian commitments under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which protect rights to nationality, property, and minority status.

However, in BJP-ruled States like Assam, Gujarat, and Maharashtra, aggressive eviction drives and targeted policing of Bengali-speaking Muslims and indigenous communities violate these frameworks, creating a humanitarian crisis.

Humanitarian Crisis

Targeting Bengali-speaking Muslims, often labelled as “Bangladeshi” or “Rohingya” without evidence, has become the new normal in a few BJP-ruled States, fuelling a humanitarian crisis. In Assam, evictions are justified as reclaiming government land, while in Gujarat and Maharashtra, urban development and policing actions disproportionately affect Muslim minorities.

These actions, often benefiting corporate interests, expose a nexus between Hindu nationalism and the economic agendas of crony capitalists, sidelining marginalised communities.

Assam: Evictions for Corporate Gain

Under the Advantage Assam 2.0 initiative, the BJP-led government has allocated vast tracts of land to corporate giants like Adani, Ambani, Patanjali, and Sri Sri Tattva for industrial and agricultural projects, while evicting Bengali-speaking Muslims and indigenous communities with minimal notice and no rehabilitation, despite Assam’s rehabilitation policy for landless people.

On June 16-17, the Goalpara district administration evicted over 4,000 belonging to 667 families from the migrant Bengali-speaking Muslim community who had been living in the Hasilabeel area for over 70 years. In 2021 at Garukhuti of Darrang district, a violent eviction displaced 2,051 families, predominantly Bengali-speaking Muslims, resulting in two deaths, including a 12-year-old boy, and over 20 injured in police firing. The land was repurposed for corporate projects. A 2023 Gauhati High Court petition for compensation was dismissed.

In 2021, evictions in Bechimari, Kuruwa Chapri, and Mangaldoi cleared land for Patanjali’s ventures, displacing Muslim and indigenous families without resettlement. The same year, 25 families were evicted from flood-prone areas like Dighali Chapori and Bharaki Chapori in Sonitpur, and similar drives in Biswanath’s Thelamara and Chariduwar targeted Muslim and indigenous communities. The land was allocated to Adani and Ambani projects.

In 2022, 37 Muslim families were evicted from 40 bighas of Satra land, with unfulfilled rehabilitation promises. Earlier evictions in Gaurijhar and Sankuchi cleared land for Sri Sri Tattva’s initiatives.

Gujarat: Chandola Lake Eviction

In Ahmedabad, the 2025 Chandola Lake eviction displaced over 8,500 families, mostly Muslims, under the pretext of environmental restoration and urban development. Homes were demolished with minimal notice, and no rehabilitation was provided. The cleared land is reportedly slated for commercial and real estate projects.

Maharashtra: Targeting Bengali-speaking Muslim workers

In the BJP-ruled Maharashtra, Bengali-speaking Muslim migrant workers, primarily from West Bengal, have faced targeted policing. State police have detained and handed over these workers to the Border Security Force (BSF) for deportation to Bangladesh, labelling them as “Bangladeshi” citizens.

West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has condemned these actions, noting that many detained workers possess valid Indian citizenship documents. For instance, in 2023, reports emerged of Mumbai police rounding up Bengali-speaking Muslims in slum areas, accusing them of illegal immigration without verification. Bangladesh often rejects these deportees, affirming their Indian citizenship, yet the harassment continues, creating fear and insecurity among migrant communities.

Constitutional and International Violations

These actions violate India’s constitutional guarantees of equality and non-discrimination. The Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA), 2019, which excludes Muslims from fast-track citizenship, and the National Register of Citizens (NRC), which left 19 lakh people (mostly Muslims) stateless in Assam, have been widely criticised as discriminatory.

The UDHR’s protections against arbitrary property deprivation (Article 17) and the ICCPR’s minority rights (Article 27) are flouted when families are evicted or workers are targeted without due process. The fabrication of Bangladeshi addresses by border police to justify deportations further underscores systemic bias, as Bangladesh frequently rejects these individuals, confirming their Indian citizenship.

The BJP’s rhetoric of “infiltrators” and “land jihad” fuels communal polarisation, consolidating Hindu votes while demonising Muslims and indigenous groups. The allocation of land to corporates in Assam and Gujarat, alongside targeted policing in Maharashtra, highlights a broader agenda prioritising economic and communal interests over constitutional values.

When families are evicted or workers are targeted without due process, it violates the protections against arbitrary deprivation of property under Article 17 of the UDHR and minority rights guaranteed by Article 27 of the ICCPR

Hate campaigns typically spike during elections (eg Delhi riots before the 2020 State polls), which may be used to polarise voters and distract from governance failures. By labelling critics as “anti-national” or “urban Naxals,” the party creates an “us vs. Them” narrative, which delegitimises opposition and curtails alternative political voices. Corporate control over media, combined with government pressure, ensures that mainstream outlets rarely challenge government narratives, limiting public scrutiny.

Marginalised Rights

Conscientious activists and social movements are critical in countering this crisis, leveraging legal, grassroots, and international platforms to uphold India’s constitutional and humanitarian commitments

Legal advocacy like filing public interest litigations (PILs) to challenge evictions, CAA, NRC, and unlawful detentions can be effective. The Supreme Court’s 2024 ruling on gubernatorial oversight offers a basis for contesting executive overreach. Organisations like Citizens for Justice and Peace (CJP) have litigated Assam’s citizenship crisis and can extend efforts to Maharashtra’s policing issues.

International pressure can be created by engaging the UN Human Rights Council and OHCHR to highlight violations in Assam, Gujarat, and Maharashtra. Reports by the Human Rights Watch on evictions and Amnesty International on arbitrary detentions provide a foundation for global campaigns.

Countering the “infiltrator” narrative on platforms like X and through independent media, sharing stories of evicted families or detained workers, humanises the crisis. Aligning with secular parties which has opposed deportations and progressive groups to form a united front against communal and corporate-driven policies may put pressure on the government.

These evictions and targeted policing of Bengali-speaking Muslim workers in BJP-ruled States expose a systemic assault on India’s secular and democratic principles. Prioritising corporate interests under initiatives like Advantage Assam 2.0 and urban development projects, while marginalising Muslim and indigenous communities undermines constitutional rights and international humanitarian laws.

Conscientious activists must harness legal challenges, grassroots mobilisation, and global advocacy to defend these politically disenfranchised groups, ensuring India honours its pluralistic ethos and delivers justice to its most vulnerable citizens.

(The author is a senior journalist from Assam)

Related News

-

Opinion: India’s subsidy rationalisation: Fiscal discipline vs social protection

-

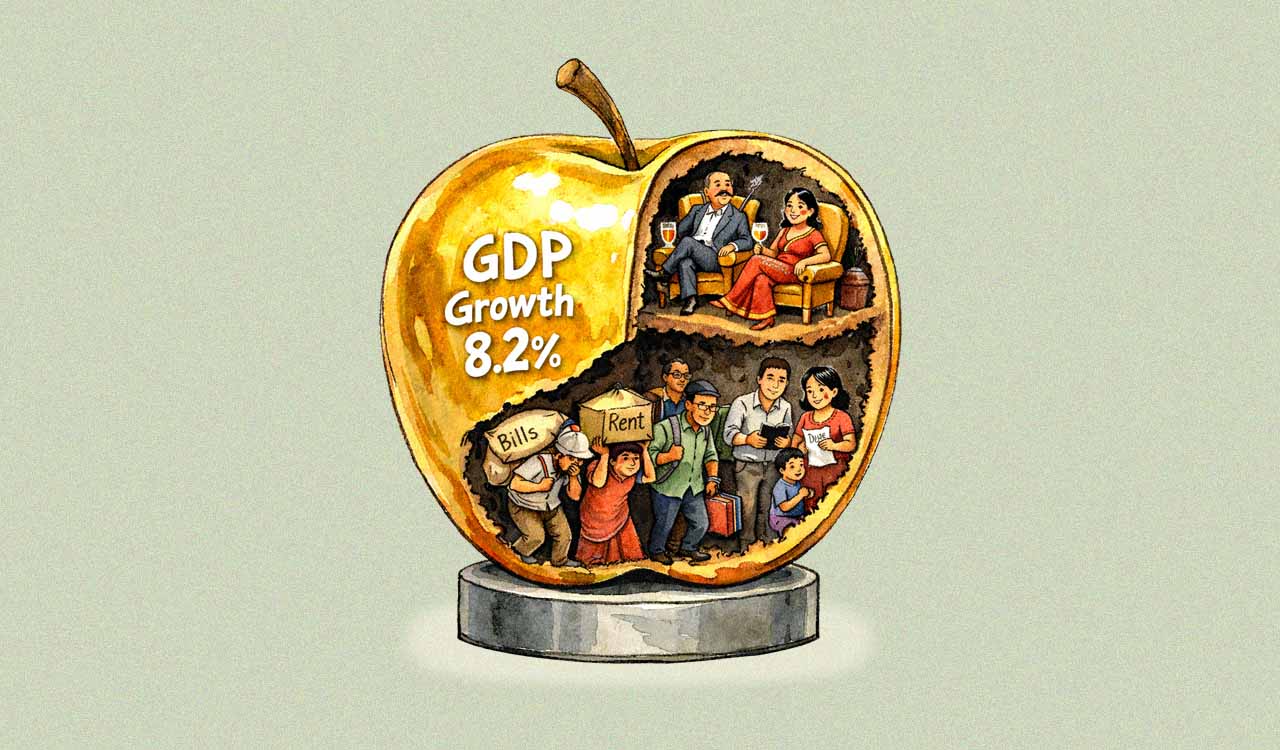

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Iran allows India-flagged tankers through Hormuz after talks between EAM Jaishankar, Araghchi

4 mins ago -

Jammu: Gunfire at event attended by NC chief Farooq Abdullah, suspect held

15 mins ago -

Terrorist hideout busted in J&K’s Rajouri; IED recovered

24 mins ago -

Blaze rips through Delhi’s Matiala slum cluster; no casualties

31 mins ago -

Damage to historical sites in Iran raises alarm about war’s impact on protected places

40 mins ago -

NIA raids underway in terror conspiracy case in J&K’s Poonch

55 mins ago -

Sensex, Nifty fall over 1 pc as Brent Crude crosses $100

1 hour ago -

Cartoon Today on March 12, 2026

1 hour ago