Opinion: AI, fewer jobs, and the search for meaning

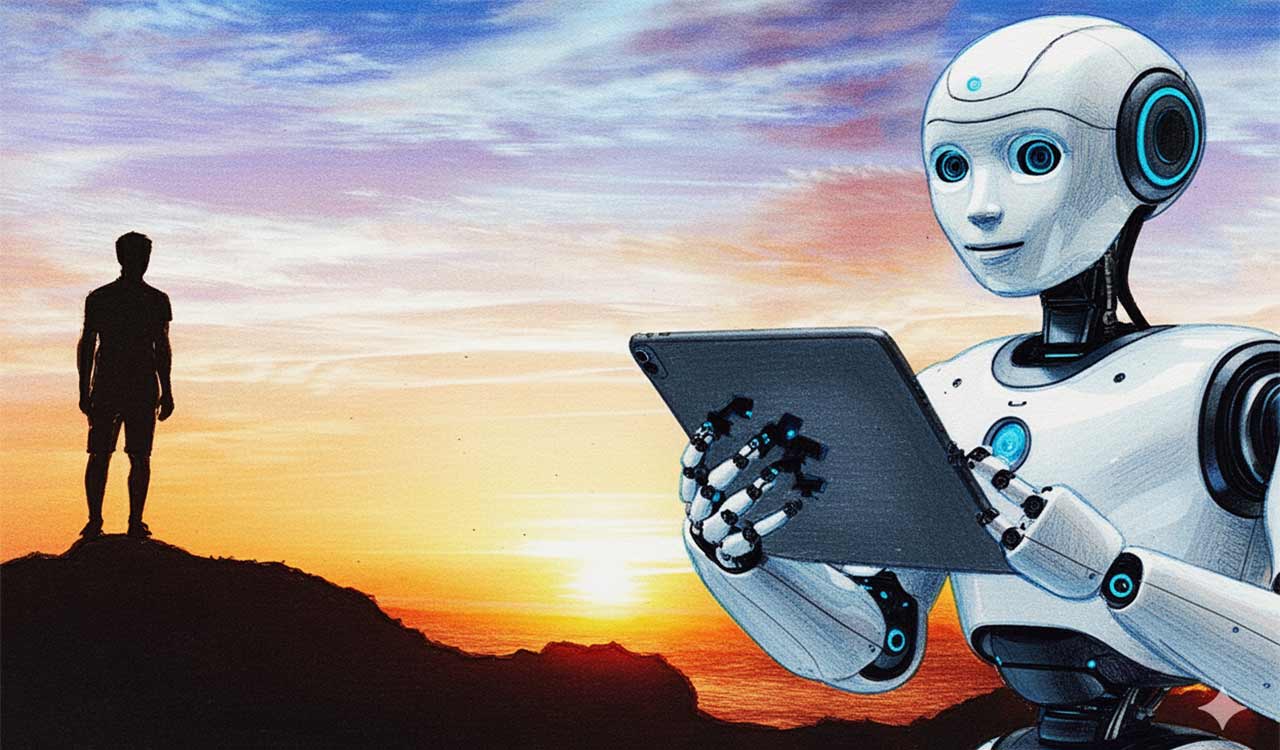

As artificial intelligence reduces human labour, existential fulfilment calls first for securing oneself against an unpredictable environment and the indifference of other living beings, including fellow humans

By B Maria Kumar

Recently, I came across an article by Tama Reeves discussing how Nobel Prize-winning physicist Giorgio Parisi supported the concerns earlier expressed by Elon Musk and Bill Gates regarding the possibility of widespread joblessness arising from the rapid spread of artificial intelligence (AI) in everyday professional life.

Also Read

This observation intrigued me and prompted me to explore the subject further. In the process, I came upon an interview that Parisi had given to an Italian news outlet in November 2024, which offered deeper insights into his perspective on the issue. In it, he observed that the rapid spread of AI is gradually and steadily reducing the need for human labour.

Even though work hours are shrinking, largely because AI and automation now perform many tasks, domestic as well as professional, that humans once carried out, Parisi argued that salaries should not be reduced in proportion to the decrease in work. This alarm has been raised by several prominent thinkers.

Earlier, Stephen Hawking cautioned that AI could make a small group of people extraordinarily wealthy while leaving the rest of humanity economically vulnerable. He, therefore, advocated sharing AI-generated profits with the wider population. Another physics Nobel laureate, Geoffrey Hinton, often called the godfather of AI, has also expressed apprehension about the possible disappearance of a significant number of jobs due to the growing influence of intelligent machines.

Even though it may not be entirely accurate to call the trend “joblessness,” it is more appropriate to see it as more free time combined with less work. Reflecting this shift, a growing number of organisations around the world have already moved, or are considering moving, from a five-day work week to a four-day schedule. At the same time, there are opposing voices that argue for longer work hours and extended work weeks. This view stems from the long-standing belief that work is something to be revered, an idealistic approach that has shaped attitudes for generations and still remains a virtue in many parts of the world.

Work As Worship?

This traditional perspective was recently challenged by researcher Mijeong Kwon and her colleagues. They found that treating work as intrinsically virtuous can actually backfire. Their findings, published on the science news website Phys.org on November 25, 2025, suggest that elevating work to a moral pedestal may alienate individuals who approach work more pragmatically, and in such cases, it can lead to personal stress and interpersonal conflict.

By securing one’s existence and resolving uncertainties, the challenge of free time becomes manageable, transforming leisure into a space for purpose and meaning

With such predictions and cautions becoming more frequent, many intellectuals have begun examining what a world with a shortage of job opportunities or more free time might look like and how human lives may change when work, along with the meaning and purpose it usually provides, becomes scarce.

As such, retirees and the elderly, who are generally relieved of the demands of formal employment, gradually settle into a particular rhythm of life by pursuing personal interests and hobbies. Some discover purpose and meaning in striving to fulfil long-cherished dreams, while others seek peace and solace in metaphysical or spiritual realms. But what happens when the productive youth and the middle-aged begin to experience a similar abundance of free time, when much of their daily work is done by artificial intelligence and automated systems?

Luxurious Leisure

This prospect can leave many unsettled, especially if they are not already engaged in meaningful forms of rest, recreation, or self-development. Stephen Hawking once referred to this condition as luxurious leisure. Long before him, Aristotle argued that the ultimate goal of work should be leisure, since happiness depends upon it. Confucius went further, suggesting that work done out of genuine interest is itself a form of leisure, for when one loves one’s work, one never truly labours.

Bertrand Russell, however, offered a cautionary note. He believed that much harm arises from treating work as worship. While Giorgio Parisi forecasts a reduction in human labour due to technological advancement, Russell anticipated something more radical, namely the idea that fewer working hours could actually enhance human happiness. Yet we also know that freedom from arduous work does not automatically translate into contentment. Leisure must be meaningfully inhabited if it is to nourish the human spirit.

This is where the need for an existential ethos comes in handy. Jean Paul Sartre reminded us that we are condemned to be free and compelled to create meaning through our choices while avoiding self-deception and bad faith. Albert Camus, by contrast, urged us to rebel philosophically against the persistent absurdity of the world as a way of affirming meaning in existence. Such conditions and their consequences inevitably place human life in a state of anxiety and uncertainty, another challenge that demands attention.

Since human life is instinctively self-preserving, a recurring question confronts us. What exactly are these meanings, purposes, and choices meant to serve? Without a consciously created rationale, the journey of life risks appearing directionless. Existential fulfilment, therefore, calls first for securing oneself against the threats of an unpredictable environment and the indifference of other living beings, including fellow humans. This vulnerability renders individuals naturally wary and xenophobic.

Fight or Flight

Therefore, the most immediate response is often to seek connection and to make friends with both people and environmental circumstances. Failing that, the instinctive alternatives of fight or flight emerge. In either case, one has to explore (the unfamiliar, threats, curiosities, etc), experience (health span, harmonious relationships with nature and fellow humans, and relative peace), and exist (safely and satisfyingly).

This strategy applies equally to situations of unemployment and reduced work. By securing one’s existence and resolving potential uncertainties, the challenge of free time becomes manageable. In doing so, leisure itself is transformed into a space for purpose and meaning, thereby aligning human freedom with a more fulfilled and secure existence.

(The author, a recipient of National Rajbhasha Gaurav and De Nobili awards, is a former DGP in Madhya Pradesh)

Related News

-

87 dead as US sinks Iranian warship off Sri Lanka

1 min ago -

Khamenei’s son seen as contender as Iran faces leadership question

2 hours ago -

Over 13,000 skip Intermediate exams in Telangana

3 hours ago -

Hyderabad: Three held with MDMA in Miyapur

3 hours ago -

Telangana govt sets deadline for Singur canal works

4 hours ago -

Minister Surekha’s daughter Susmitha lays claim to Parkal Assembly seat

4 hours ago -

Revanth Reddy govt’s 99-day action plan clouded by funding ambiguity

4 hours ago -

Middle East Crisis: Flights to India partially resumed after five-day disruption

4 hours ago