Opinion: Grain vs Greed — Assault on Telangana farmers and future

Check dams revived Telangana’s drought-prone agriculture, but rampant illegal sand mining and sabotage now threaten these gains

By Chandri Raghava Reddy

After decades of neglect and apathy, farmers of Telangana, defeated by fickle monsoons and persistent droughts, found hope in the form of check dams. These small yet dependable structures became vital sources of irrigation water security. These low-cost barriers, simple structures of concrete, earth, or stone built across rivers and rivulets, store water, slow runoff, reduce erosion, and promote groundwater recharge through infiltration. In fact, check dams are recognised globally as effective tools for rainwater harvesting, and have proven to transform farmers from despair to hope.

Also Read

Aquifer Recharge

The International Water Management Institute recognises check dams as key instruments for managed aquifer recharge in semi-arid regions. It has conducted extensive studies on their role in capturing surface runoff to enhance groundwater storage, improve water security, and build climate resilience. Research highlights increased groundwater recharge and agricultural productivity due to check dams.

The United Nations, through agencies like FAO, UNDP, and UNEP, also supports check dams as part of rainwater harvesting and watershed management for soil conservation, erosion control, flood mitigation, and groundwater recharge. FAO includes check dams in its watershed management guidelines for gully control and runoff reduction. The UNDP has funded projects involving check dams for community resilience and drought adaptation. UN reports situate check dams within Sustainable Development Goal 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation), highlighting them as low-cost, decentralised solutions for arid regions.

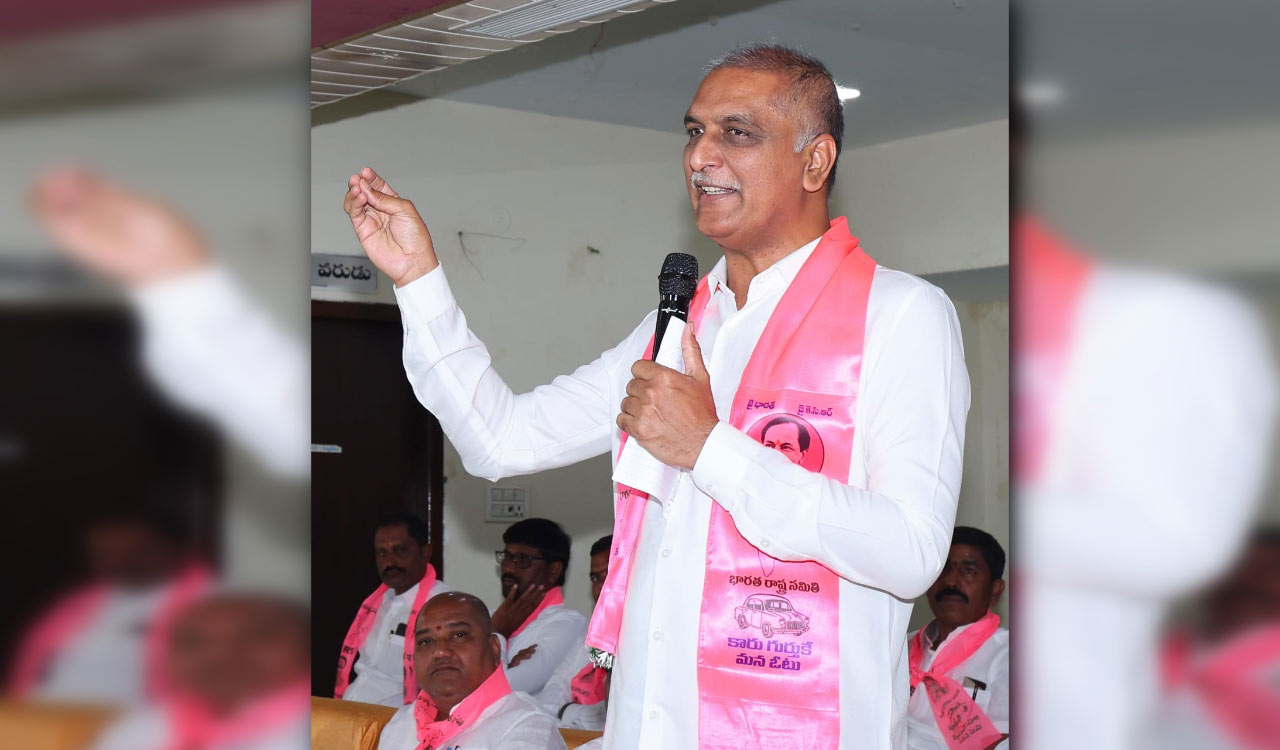

The BRS government constructed about 1,250 check dams across the State by 2022, transforming agriculture, especially for farmers along rivers and streams

The importance of check dams was recognised centuries ago, and their role endured across generations. Check dams have ancient roots in India, with evidence of water-harvesting structures dating back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, including bunds and small dams at sites such as Dholavira and other Harappan settlements.

The most prominent early example is the Kallanai Dam, built across the Kaveri River in Tamil Nadu by the Chola king Karikala around the 2nd century CE. This masonry diversion structure, still in use today, functioned similarly to a large check dam by regulating river flow and enabling irrigation, making it one of the oldest surviving water-regulator structures in the world. Archaeological evidence also points to dams and reservoirs in central India from the 2nd–1st century BCE, associated with early irrigation for rice cultivation.

In the modern era, large-scale construction of check dams under government programmes gained momentum from the 1960s. Community and NGO-led efforts further popularised them during the 1980s and 1990s.

Water Woes to Water Ways

Before Telangana’s formation in 2014, watershed management in undivided Andhra Pradesh favoured coastal Andhra and Rayalaseema, while sidelining the Godavari belt of Telangana. With few irrigation initiatives and priority given to downstream coastal Andhra, Telangana was forced to depend on erratic monsoons and depleting groundwater. Over six decades, traditional tanks deteriorated, resulting in the irrigated area dropping from 48% in 1960 to 11% by 1998.

Over-exploited borewells failed frequently, crop losses, and mounting debts led to thousands of farmer suicides. This perceived discrimination deepened regional inequities, culminating in the Telangana statehood movement.

The transformation of Telangana’s irrigation sector began with State formation. The new State inherited severe water scarcity, with only 23.44 lakh acres under irrigation and villages plagued by migration and farmer suicides. The first Chief Minister, K Chandrashekhar Rao, who made irrigation his rallying cry — ‘water for every acre,’ launched ambitious programmes such as Mission Kakatiya, which revived over 46,000 ancient tanks, and the Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Scheme (KLIS), the world’s largest lift irrigation project, designed to harness the waters of the Godavari.

The Bharat Rashtra Samithi government constructed about 1,250 check dams across the State by 2022, implementing them in two phases. Phase I integrated check dams into Mission Kakatiya using Nabard funding for rapid execution. Phase II, planned for rollout starting in 2023, focused on underserved tributaries. In Karimnagar and Rajanna Sircilla districts of northern Telangana, 24 check dams were built along the Manair River and Mulavagu streams, transforming villages once considered hotbeds of naxalite activities into granaries.

This changed the fate of farmers, particularly those cultivating on both banks of rivers and streams. Most are marginal and small farmers. By impounding monsoon runoff, check dams created small reservoirs that ensured water availability throughout the year. Farmers use motors to lift water directly for irrigation in both kharif and rabi seasons. Check dams helped recharge groundwater, reportedly raising levels by 5 to 10 feet and refilling borewells on either bank.

This phenomenal initiative stabilised yields, reduced the cost of cultivation and boosted farmer incomes. These also supported fisheries. Once drought-prone riparian lands, where only ‘Sarkar Tumma’ grew, were transformed into thriving paddy fields. Irrigated land surged by 284% to 90 lakh acres, effectively “drought proofing” the State and curbing migration.

Greed in the Riverbeds

The sand mafia has operated with near impunity for over four decades. Since the 1980s building boom, river sand from the Godavari, Krishna, Manair, and smaller streams became the preferred construction material. This shadowy network, comprising local contractors, leaders, middlemen, and musclemen, often functioned under political patronage.

Check dams, by trapping monsoon runoff and creating year-round reservoirs, transformed everything. They submerged vast deposits of high-quality sand under meters of water, making mechanised extraction impossible without first breaching the structures. What was once an easy, low-risk racket turned into a high-stakes criminal enterprise. Unable to mine legally under stricter rules and physically blocked by check dams, the mafia resorted to sabotage — draining reservoirs, cutting embankments, and even blasting dams to access sand. Environmental laws, too, were compromised, prioritising profit over sustainability.

Sources suggest that over 420 structures have been damaged in the past 18 months, many during the 2025 monsoon, allegedly due to illegal sand mining activities. Incidents along the Manair River have escalated since 2024. On November 21, blasts at Gumpula Tanugula, gelatin sticks suspected, were confirmed as sabotage by fact-finding panels. A second incident on December 17 near Adavisomanpalli further indicates the audacity of the sand mafia and reflects the failure of state machinery in arresting the culprits. Had those involved in the November blast been identified and punished, anti-social elements might not have dared to strike again.

These acts directly undermine farmers’ interests and contradict the state’s commitment to water conservation. Farmers dependent on check dams for kharif and rabi crops now face an uncertain future.

The previous government’s initiatives on check dams were commendable steps towards equitable water management, but their benefits have been undermined by weak regulatory enforcement now. Illegal mining not only destroys infrastructure but also perpetuates inequality, benefiting a few at the expense of rural livelihoods. Telangana needs stringent monitoring and strict enforcement of water and environment laws. Protecting farmers is essential to safeguard the State’s agrarian backbone, ensuring that post-2014 gains endure against exploitative forces.

Telangana’s check dams embody a ‘trickle-up’ model, expanding farmlands and fostering sustainability. But the mafia’s greed, pitting plunder against sustenance, threatens reversal. Without decisive action, rivers will dry, fields will lie fallow, and hope will erode.

(The author is Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Hyderabad)

Related News

-

Middle East airspace crisis hits Indian travel bookings

9 mins ago -

Adani confirms Haifa Port fully secure amid Iran-Israel conflict

14 mins ago -

Trump orders strikes on Iran, announces death of supreme leader Khamenei

27 mins ago -

Cyberabad to launch tech-driven student transport system by June 2026

38 mins ago -

Hyderabad police bust major food adulteration racket in Sanathnagar

47 mins ago -

KTR tears into Bulldozer Raj by Revanth Reddy government, calls for unity among Musi oustees

1 hour ago -

Massive explosion rocks Tehran as Israel targets city centre

2 hours ago -

Veteran Deepak Gupta appointed CMD of GAIL

2 hours ago