Opinion: Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Scheme — Telangana’s watershed moment

The Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Scheme (KLIS) has transformed Telangana’s agriculture, reversing decades of drought and despair. The project is also about identity, dignity, and justice for State’s farmers

By Chandri Raghava Reddy

Farming sustains life, and life alone. Never in history has a farmer become rich solely by depending on cultivation. There is no breakeven point in agriculture. In fact, pauperisation is more the norm in agriculture than the exception, especially in Telangana. Given the extent of vulnerabilities faced by farmers in Telangana, induced by nature and perpetuated by the state over decades, the degree of pauperisation here has been more severe than in any other part of the country.

Also Read

Agriculture in Telangana has long been a gamble. Historically rooted in subsistence farming, most farmers today own less than five acres. The semi-arid climate allowed cultivation only during the rainy Kharif season, leaving land fallow in Rabi. Farmers relied on open wells to grow paddy, and only a few with sufficient water cultivated a second crop on limited land.

As commercial farming took hold under the neo-liberal economy, the transition intensified agrarian distress, especially for those without irrigation. Though the scale of crisis varied by landholding size, the threat was widespread and persistent, turning farms into sites of risk and uncertainty.

Farmers relying on open wells faced high costs as traditional water-lifting methods gave way to oil pumpsets. Traditionally, irrigation was limited to gravity-fed areas, but pumpsets allowed water-lifting to higher ground. Electrification later reduced dependence on diesel and lowered maintenance but introduced new challenges. As farm electricity spread and irrigation subsidies grew, commercial agriculture surged. Nearly every farmer aspired to cultivate paddy, intensifying the competition for water, deepening agrarian risks in a region already strained by its semi-arid landscape.

The Dark Decades

Until the 1980s, open well irrigation persisted in Telangana. The arrival of borewell machines transformed this, making borewells a lifetime goal for farmers across castes. The public distribution system’s rice-centric policy created a state-driven market for paddy, forcing small and marginal farmers to convert chalka lands into paddy fields. Borewell-based irrigation, electrified pumps, and water pipelines became widespread.

By the late 1990s, over-extraction led to severe groundwater depletion. This gave rise to a ‘water treadmill’, digging deeper borewells each year to sustain paddy, pushing farmers into a web of debt. A decade of droughts further intensified the crisis. The period between the 1990s and 2015s marked some of the darkest years for Telangana’s agriculture, worsened by policy neglect and a lack of state support for struggling farmers.

K Chandrashekhar Rao championed the cause of Telangana’s farmers during the statehood movement by placing water as one of the three core demands and translated that vision into stupendous outcomes

The reality of river water availability was distorted by the narrative that both Krishna and Godavari rivers could not reach Telangana farms due to the terrain and had to flow downstream to quench the unending thirst of a few capitalist Andhra farmers. The underlying agenda was clear — to keep farmland prices in Telangana low so that Andhra capitalists could acquire it at throwaway rates. Their land hunger stemmed from a waning hold over agriculture in Andhra and accumulated capital through contracts and businesses. It was often said that the sale of one acre in Andhra could fetch at least five acres in Telangana, especially near Hyderabad. The massive potential for Hyderabad’s expansion shaped the capitalist class’ long-term vision for acquiring land in Telangana.

By the time Telangana achieved statehood, nine out of its ten districts were designated as backward by the Centre, an indicator of prolonged neglect and institutional apathy. Yet this reality was rarely acknowledged by the hegemonic media, vernacular or English, print or electronic. While ‘water’ was a central slogan of the Telangana movement, symbolising discrimination, the compromised media reduced it to a self-serving political rhetoric, stripping it of its collective significance and framing it as an opportunistic rather than a just demand.

Well, the saga of sorrow — of parched soils and weary souls in Telangana, sprang back to life after the inauguration of the world’s largest lift irrigation scheme, ‘Kaleshwaram’. To both naïve minds and the corrupt elite, it must be clarified that it is a multi-stage lift irrigation scheme comprising a series of barrages, pumping stations, storage reservoirs, and canals, powered by the dedication of Telangana’s engineers, political representatives, and most notably, the vision of the then government.

It is hard to imagine the state of Telangana agriculture without the grit and determination of former Chief Minister K Chandrashekhar Rao who not only monitored the project’s progress with relentless focus but also challenged the ‘mispropaganda’.

From Chalkas to Sirulu

The Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Scheme (KLIS) was inaugurated in June 2019. One of the most visible impacts of KLIS is the ongoing, spectacular expansion of paddy cultivation in Telangana. Since paddy requires reliable irrigation, Kaleshwaram is steadily channeling water, either directly through canals under ayacut or by stabilising groundwater through rejuvenated rivers and rivulets, making its presence felt in the fields.

This transformation has been further supported by state initiatives like Rythu Bandhu and Rythu Bima, which are continuously uplifting farmers’ morale, confidence, and security. What were once chalkas (marginal lands) are becoming sirulu (sources of wealth). For many families, farming is now bringing not just survival but celebration. This agricultural resurgence is also generating employment for landless households, breathing renewed life and dignity into rural Telangana.

Beyond crop yields, Kaleshwaram has improved groundwater levels, reduced financial risks for farmers and revived ecological systems. By filling water bodies and reservoirs, it has raised the groundwater table by an average of over 4 metres, as documented in hydrological studies and echoed across social media. This has also led to a decline in fluoride contamination levels in groundwater, a longstanding issue in several districts.

Reliable irrigation has reduced farmer suicides, with Telangana registering one of the sharpest declines, earning it recognition as a model for agricultural resilience. Increased agricultural output spurred Telangana’s rural economy by increasing demand for agricultural inputs and services. The expansion of area under cultivation created employment opportunities in rural areas, from labour for field operations to jobs in input supply chains. It has led to increased spending on local goods, such as groceries, clothing, and household items, invigorating village markets and small businesses.

Another often-overlooked benefit of Kaleshwaram is the indirect gains to farmers. On average, each farmer is estimated to have saved at least Rs 1 lakh over the past five years as a result of KLIP. Here’s how: Imagine if Kaleshwaram had not stabilised groundwater levels across Telangana, every farmer, regardless of landholding size, would have invested in digging a new bore well. The minimum cost of drilling a borewell in Telangana is no less than Rs 1 lakh rupees to ensure water reaches the field.

The economic ripple effects extend to towns and semi-urban areas in Telangana. As rural households gain purchasing power, they spend more on consumer durables, such as electronics and appliances, construction materials, and services such as healthcare and education. This increased rural spending drives growth in retail, transportation, and construction sectors in nearby towns, creating jobs and boosting local enterprise.

KLIS stands as a testament to the grit and determination of political leadership committed to Telangana’s development. In post-independence India, agricultural development often remained confined to slogans like Jai Kisan or Rythe Raju (‘Farmer is King’), but these ideals rarely translated into action, scuttled by bureaucratic inertia and electoral compulsions. Jai Kisan became Nei Kisan, and Rythe Raju reduced farmer to a labourer.

Leaders like Neelam Sanjeeva Reddy and YS Rajasekhara Reddy in the undivided Andhra Pradesh made efforts for farmers’ welfare. However, subsequently, as caste-based politics took precedence, the political will to prioritise agrarian interests diminished.

An exception to this kind of politics is K Chandrashekhar Rao. He not only championed the cause of Telangana’s farmers during the statehood movement, by placing water as one of the three core demands, but also translated that vision into stupendous outcomes. KLIS is the living proof of that vision. KLIS is not merely about irrigation, it is about identity, dignity, and justice for Telangana farmers.

(The author is Professor, Department of Sociology, University of Hyderabad)

Related News

-

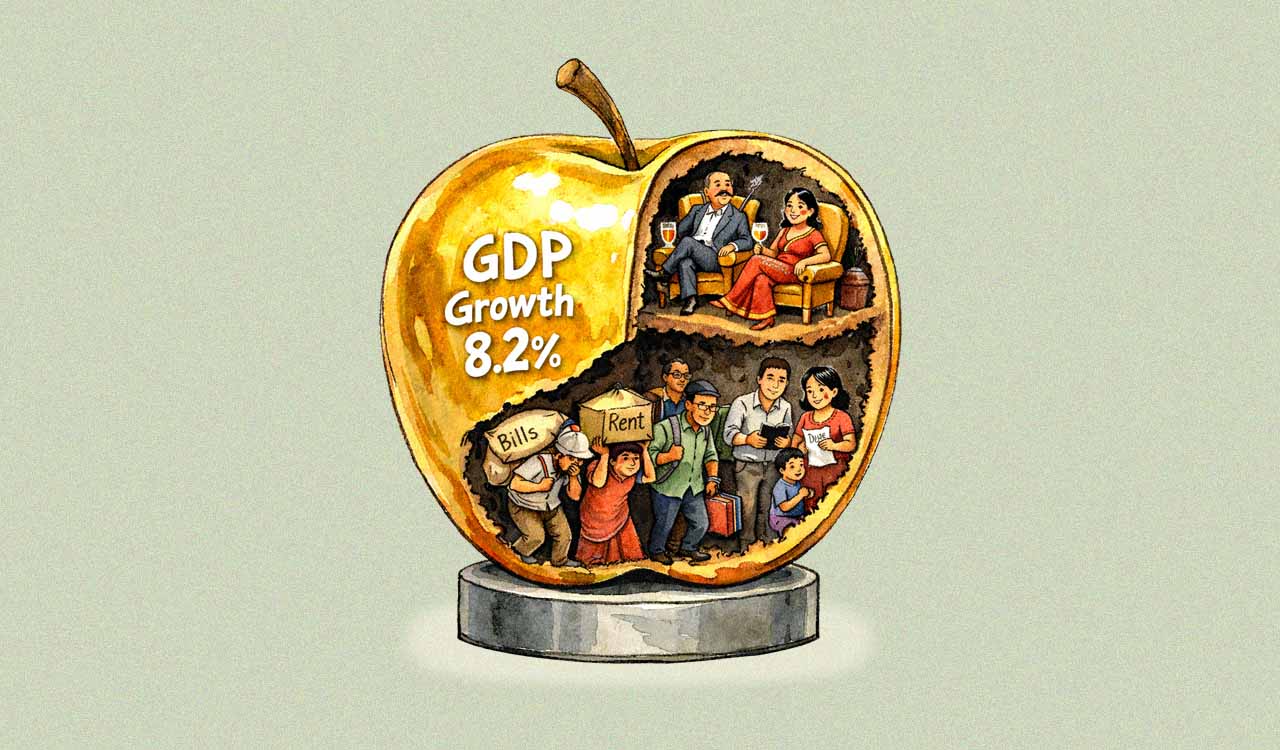

Opinion: India’s subsidy rationalisation: Fiscal discipline vs social protection

-

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Maize farmers in Khammam in distress as Markfed yet to open procurement centres

-

SCR RPF rescues 92 children under ‘Nanhe Farishte’ operation in February

24 mins ago -

Inorbit Mall Cyberabad hosts live Qawwali, classical music events in March

54 mins ago -

BIMTECH partners with Hexalog to launch Centre of Excellence in supply chain & logistics

1 hour ago -

Emerging technologies like quantum computing and HPC set to transform startups and enterprises

1 hour ago -

KTR distributes Ramzan ration kits, targets Congress over welfare schemes

1 hour ago -

ITC Mission Sunehra Kal organises Water Mela in Bhadrachalam to promote water conservation

1 hour ago -

India emerges as third-largest cross-border hiring pool: Report

2 hours ago -

Two held with 1.74 kg ganja in Hyderabad’s Attapur

2 hours ago