Opinion: Let public, pvt sectors thrive together

By Seela Subba Rao The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India’s report on Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs) presented to Parliament in December 2021 showed mixed results – the good, the bad and the downright ugly. After examining a total of 607 CPSEs as on 31 March 2020, the picture brought out by CAG […]

By Seela Subba Rao

The Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) of India’s report on Central Public Sector Enterprises (CPSEs) presented to Parliament in December 2021 showed mixed results – the good, the bad and the downright ugly. After examining a total of 607 CPSEs as on 31 March 2020, the picture brought out by CAG is quite dismal. The report disclosed diminishing returns for the government and the taxing drain of public resources by many mismanaged PSUs.

The investments in government companies and corporations increased 23.15% to Rs 28,99,833 crore in 2019-20 from Rs 23,54,708 crore in 2018-19. Return on equity in the case of 224 CPSEs was 15.31%. Three sectors, namely power, petroleum and coal, and lignite contributed maximum profits — Rs 95,311 crore — to the Centre’s kitty and accounted for 67.61% of the total profits of government companies. However, 181 government companies incurred losses during 2019-20. Of this, 115 CPSEs incurred losses for three to five years continuously for the last five years.

In addition to CPSEs, State government-owned PSUs and statutory corporations are under financial stress. These include State Road Transport Corporations, electricity generation & distribution companies and financial companies. Losses incurred by State PSUs accumulated at a whopping Rs 97,078.61 crore which is almost three times that of central PSUs as on 31 March 2020. No doubt, the PSUs are bleeding.

Common Problems

Some common problems for such huge losses include the usage of old and obsolete plants and machinery, outdated technology and practices, excess manpower, extravagant trade unionism and weak marketing strategies. Other deterrent factors are allocation of inadequate resources, delays in filling top posts, tight regulations and procedures for investment and restrictions on the functional autonomy of employees.

In the initial periods, certain PSUs were advised to invest in infrastructure/capital expenditure to provide services in different parts of the country, but subsequently, rules/policies were framed to extend preferential treatment to private players. PSUs are headed by persons with zero domain knowledge instead of professionals in the relevant field. In certain sectors, inefficiency and indifference of employees due to job security too was a reason for the dismal performance. Improper price policy of the government is another factor which affects the price of their products or services. When a PSU is not making a profit, unlimited funding was made available without any rationale.

Strategies Adopted

No doubt, the government has made earnest efforts to revive loss-making PSUs. The Ministry of Disinvestment was created in 1999 and its objective was not just to raise revenue, but also to improve the efficiency of PSUs. The Board for Reconstruction of Public Sector Enterprises (BIFR) was created to track their performance and advise the government on restructuring, revival, investment etc.

Three categories of PSUs were formed: Maharatnas, Navaratnas and Miniratnas and performance contracts/MoUs were signed with the government to provide incentives for better performance. Now the Board has been scrapped as part of a new strategy to revive and disinvest sick public sector units. In a few cases, the closure of CPSEs has been approved by the government as there is no point in putting more money in the sinking ship.

The government announced the policy of strategic disinvestment on 1 Feb 2021. It aims to sell a substantial portion of its stake to private players in both loss and profit-making PSUs and use the proceeds to finance various social sector and development programmes.

In the initial years, the public sector occupied the commanding heights and played a key role in catalysing industrialisation, regional development, national security and fulfilment of a host of national goals.

The limitation of the earlier development model led to a significant course change after 1991 – the post-liberalisation shifts to markets and the private sector as engines of growth. The elements of liberalisation involved free entry to private sector firms in industries reserved exclusively for PSUs and disinvestment of a small part of the government’s shareholding and listing of PSUs on the stock exchange.

Strategic Disinvestment

It is pertinent to mention that India has not gone for large-scale privatisation/strategic disinvestment in contrast to many other countries in East Europe and Latin America. There is a need to fine-tune the policy of strategic disinvestment. The perpetually loss-making PSUs of both the Centre and States are a huge burden on the country’s sagging economy. The colossal amount of capital stuck in these enterprises could be used to boost public spending on healthcare, education and infrastructure considerably and create new job opportunities.

A curb should be imposed on PSUs to disallow them from floating new subsidiaries or joint ventures to stop the proliferation of these enterprises further. Utmost care may be exercised to appoint PSUs’ chairmen to drive performance and they should be apolitical. PSUs should be allowed to function with full autonomy coupled with corporate governance and business standards. Accountability should be fixed for all decisions taken by them.

The Department of Public Enterprises has initiated revamping of performance monitoring systems of CPSEs to make them more transparent, objective and forward-looking based on sectoral indices. More performance contracts/MoUs must be executed by stipulating timelines for ailing PSUs failing which they may be wound up or taken over by private players.

Differential treatment for service and non-service sector PSUs is much needed. Disinvestment is the right approach for the PSUs in the service sector whereas, for the non-service sector, a mixed approach with a combination of disinvestment and performance contract/MoU is a prerequisite. Getting the government out of the business and laying the foundation for rapid growth by accelerating India’s infrastructure plans is the road ahead. A ten-year plan to divest at least 49% of state holdings in PSUs may be chalked out on a need basis. Thereafter shifting the proceeds into the strategic investment fund must be worked out to focus on core infrastructure sectors.

Complete privatisation of PSUs is no panacea. As long as mixed economy remains the cardinal principle in our policy framework, PSUs will continue to be an important part. A right balance between the two sectors can perform better and meet the social and commercial targets of the economy.

(The author is former Assistant General Manager, Nabard)

Related News

-

Harish Rao accuses Revanth Reddy of stealing credit for BRS projects

-

Telangana’s finances stand on firm ground, not shaky during BRS regime

-

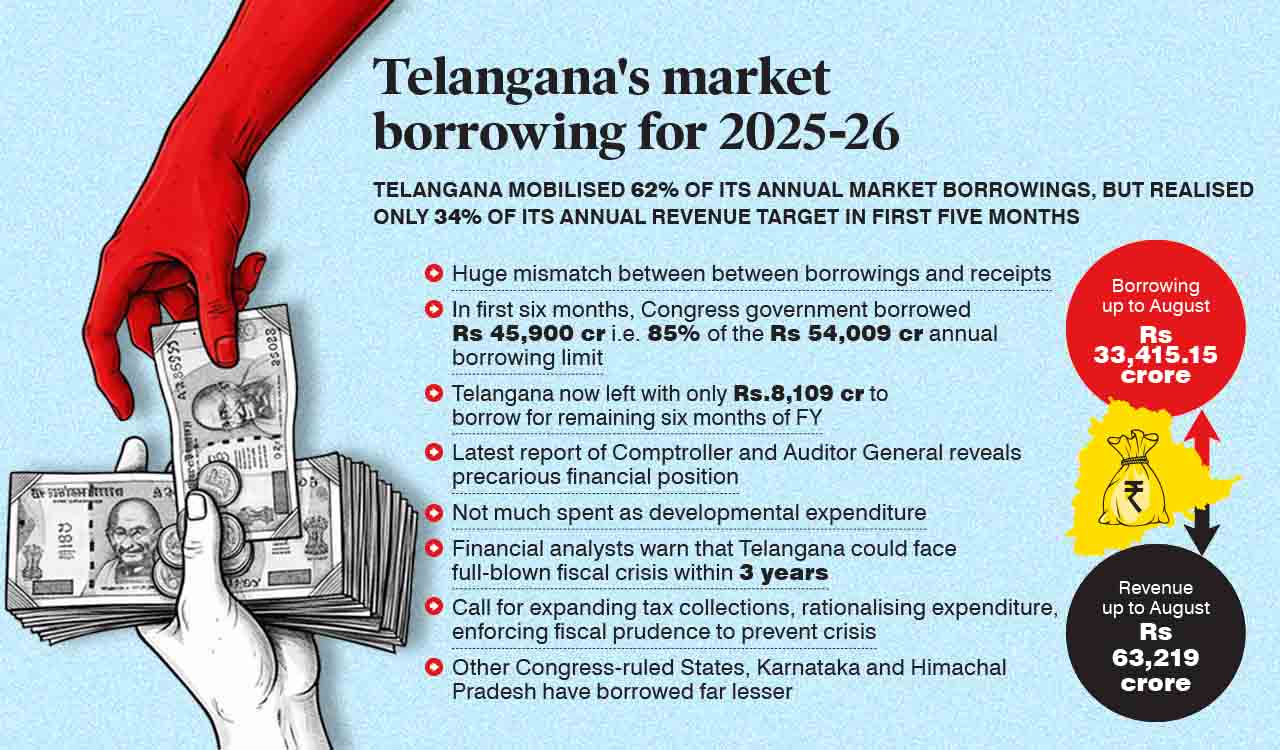

Telangana exhausts 85 per cent of annual loan limit in six months as revenues lag

-

CAG report proves Revanth Reddy’s interest burden claim to be false, loan burden exaggerated by Congress to cover up own follies

-

HCA: Visaka Group will spend entire amount of Rs 64 crore on infrastructure in districts, says Vivek

2 hours ago -

Sports briefs: Indian boxers shine on day four at World Boxing Futures Cup

6 hours ago -

Nikki Pradhan achieves another milestone, completes 200 international caps

7 hours ago -

Telangana sets up Rythu Discom, liabilities of Rs 71,964 crore shifted

7 hours ago -

Iran targets ships, Dubai airport in Gulf escalation

7 hours ago -

FIH Qualifiers: India scores big win against Wales, storm into semifinal

7 hours ago -

India allows FDI under automatic route for firms with less than 10 per cent Chinese stake

7 hours ago -

IEA agrees to record emergency oil release to calm global prices

7 hours ago