Opinion: Who pays the cost of Trump’s India tariff?

Experience from 2018-19 shows tariffs get passed on to consumers; the 2025 round may be more inflationary, leaving US consumers with higher prices and fewer choices

By Dr Jadhav Chakradhar, Dr Arun Kumar Bairwa

On August 6, 2025, the US government announced a steep tariff hike on Indian goods and services from 25 per cent to 50 per cent, effective August 27. The new policy targets USD 54 billion worth of India’s USD 86.5 billion annual exports to the US, citing New Delhi’s trade links with Russia.

Also Read

Since American consumers rely heavily on Indian products, such as textiles, gems, and IT services, the fallout will depend largely on one key factor: the price elasticity of demand — how sensitive buyers are to price changes, how elasticity will shape consumer behaviour, market outcomes, and the broader economic consequences for the US.

Elasticity in Tariff Context

Price elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of quantity demanded to price changes. For goods with inelastic demand (elasticity < 1), quantity purchased changes little when prices rise. For goods with elastic demand (elasticity > 1), even a small price increase can trigger sharp drops in consumption. A 50 per cent tariff raises import costs significantly. For example, a USD 100 textile item that previously cost USD 110 with a 10 per cent tariff could now cost USD 125. Whether Americans keep buying at higher prices depends on necessity, the availability of substitutes, and household income levels.

Pharma and IT Services

India provides about half of America’s generic medicines — worth USD 12.7 billion in 2024. Most are exempt from the tariff, but related medical supplies and equipment are not. Generics have a very low elasticity (0.2-0.4) because they are essential, and substitutes are scarce. Even with a 10-15 per cent price increase, demand will likely remain stable, meaning patients — especially those managing chronic illnesses — will bear the extra costs. This could push up healthcare expenses, hitting low-income households hardest.

India’s USD 30 billion IT and BPO services sector is another inelastic category (elasticity around 0.5). US businesses in finance, retail, and tech depend heavily on India for affordable software development and customer support. Few alternatives can match India’s scale and efficiency. If costs rise — whether from tariffs, reduced demand, or Indian retaliation — companies may pass the burden to consumers. For instance, a 10 per cent cost hike in IT services could translate into a 1-2 per cent increase in prices for banking, retail, or e-commerce services.

Textiles and Jewellery

Textiles and apparel (USD 10 billion) and gems and jewellery (USD 11.9 billion) fall into the elastic demand category (elasticity 1.2-1.5). While Indian products are valued for quality, substitutes exist in countries like Bangladesh (19 per cent tariff) and Vietnam (20 per cent tariff). A 50 per cent tariff could raise retail prices by 10-15 per cent, prompting budget-conscious shoppers to switch to cheaper alternatives.

For example, a USD 50 cotton shirt from India could now cost USD 62.50. Still, switching won’t be painless — Vietnam’s textile capacity is about 30 per cent smaller than India’s, which could cause shortages or force quality compromises.

For inelastic goods like generics and IT services, Americans will face higher prices without easy alternatives, straining both household budgets and corporate supply chains

Jewellery tells a similar story. Mid-range diamonds and gold pieces could see demand fall by 15-20 per cent as buyers opt for lab-grown stones or delay purchases. Major US retailers like Tiffany & Co, which source heavily from India, may face supply disruptions and reduced variety.

Electronics & Components

India’s electronics exports to the US are smaller (USD 1.4 billion) but still important, especially components for iPhones. These have a moderately elastic demand (elasticity 0.8-1.0). While semiconductors are exempt, related parts will be hit, pushing up smartphone or laptop prices by 5-7 per cent. Consumers loyal to premium brands like Apple may absorb the hike, but more price-sensitive buyers could switch to cheaper models or delay upgrades. Since US manufacturers can’t quickly replace India’s output, alternative supply chains are limited.

Consumer Behaviour

The tariff’s effect will vary by income group and product type. Low-income households, being more price-sensitive, will cut back sharply on elastic goods like clothing. Higher-income households may absorb increases for essentials like generics but reduce discretionary purchases like jewellery. Overall, demand for the affected goods could drop by 5-10 per cent, based on weighted elasticity estimates, adding an estimated 0.2-0.3 percentage points to US inflation (PCE index).

Retailers such as Walmart — sourcing a quarter of their textiles from India — are likely to pass on 70-80 per cent of the extra cost to consumers. Domestic producers, shielded from competition, could also raise prices. Experience from the 2018-2019 tariff hikes shows near-complete pass-through of costs to consumers, and the 2025 round may be even more inflationary.

Some Indian exporters may absorb 10-15 per cent of the tariff to remain competitive, but most of the cost will be passed to US buyers. India could also redirect exports toward the EU and ASEAN nations — where it has trade agreements — reducing supply for US markets, especially in inelastic goods. If India retaliates with tariffs — for example, on US almond exports (USD 1 billion), US consumers could face higher nut prices, as almonds have moderately elastic demand (around 1.0).

The 50 per cent tariff risks creating a lose-lose situation. For inelastic goods like generics and IT services, Americans will face higher prices without easy alternatives, straining both household budgets and corporate supply chains. For elastic goods like textiles and jewellery, demand shifts could shrink variety, disrupt markets, and stoke inflation.

With less than a month before implementation, the clock is ticking for diplomatic negotiations. Without a resolution, US consumers are likely to enter a period of higher prices and fewer choices — driven by the unforgiving logic of demand elasticity.

(Dr Jadhav Chakradhar is Assistant Professor of Economics at the Centre for Economic and Social Studies [CESS], Hyderabad. Dr Arun Kumar Bairwa is Assistant Professor of Economics at the Indian Institute of Management, Amritsar)

Related News

-

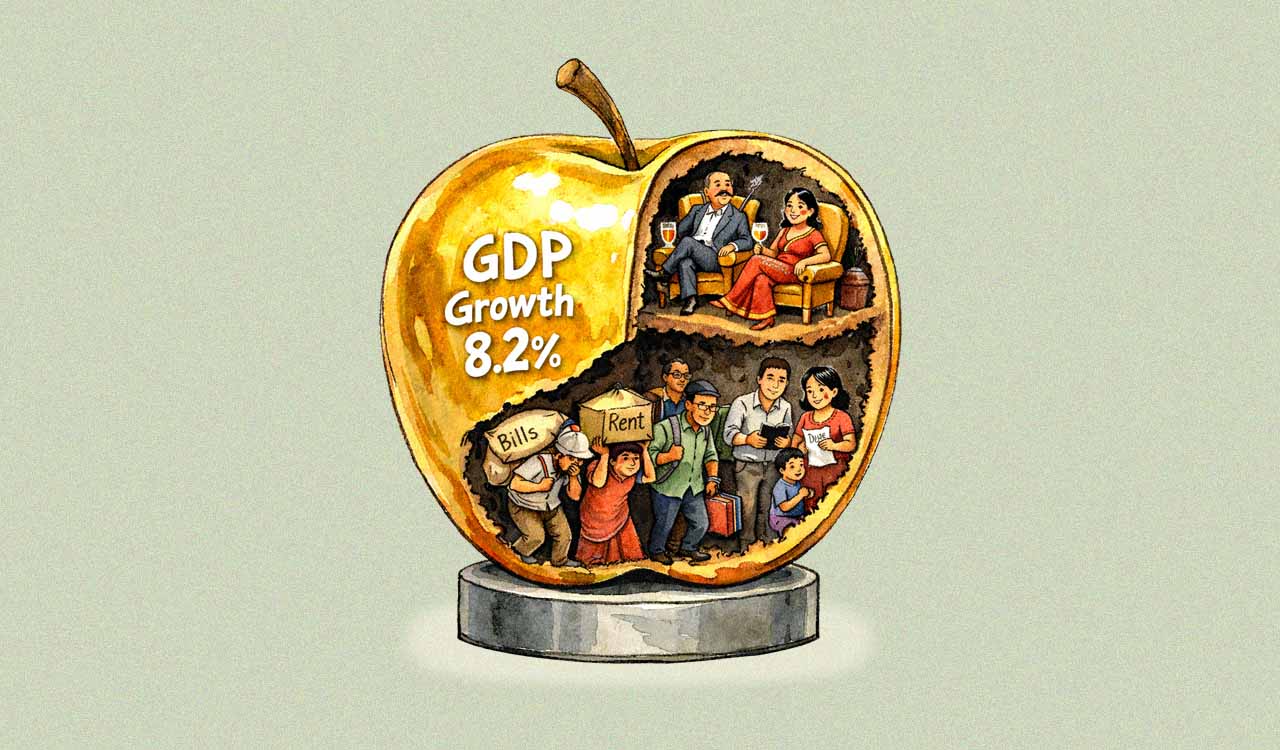

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

SICA hosts memorial Carnatic concert in Hyderabad

3 hours ago -

National IP Yatra-2026 concludes at SR University in Warangal

3 hours ago -

Iran war may push fuel prices up: Harish Rao

3 hours ago -

Rising heat suspected in mass chicken deaths at Siddipet poultry farm

4 hours ago -

Annual General Body Meeting of the Rugby Association of Telangana held

4 hours ago -

Godavari Pushkaralu to be organised on the lines of Kumbh Mela: Sridhar Babu

4 hours ago -

Para shuttler Krishna Nagar clinches ‘double’ in 7th Senior Nationals

4 hours ago -

Madhusudan clinches ‘triple’ crown in ITF tennis championship

4 hours ago