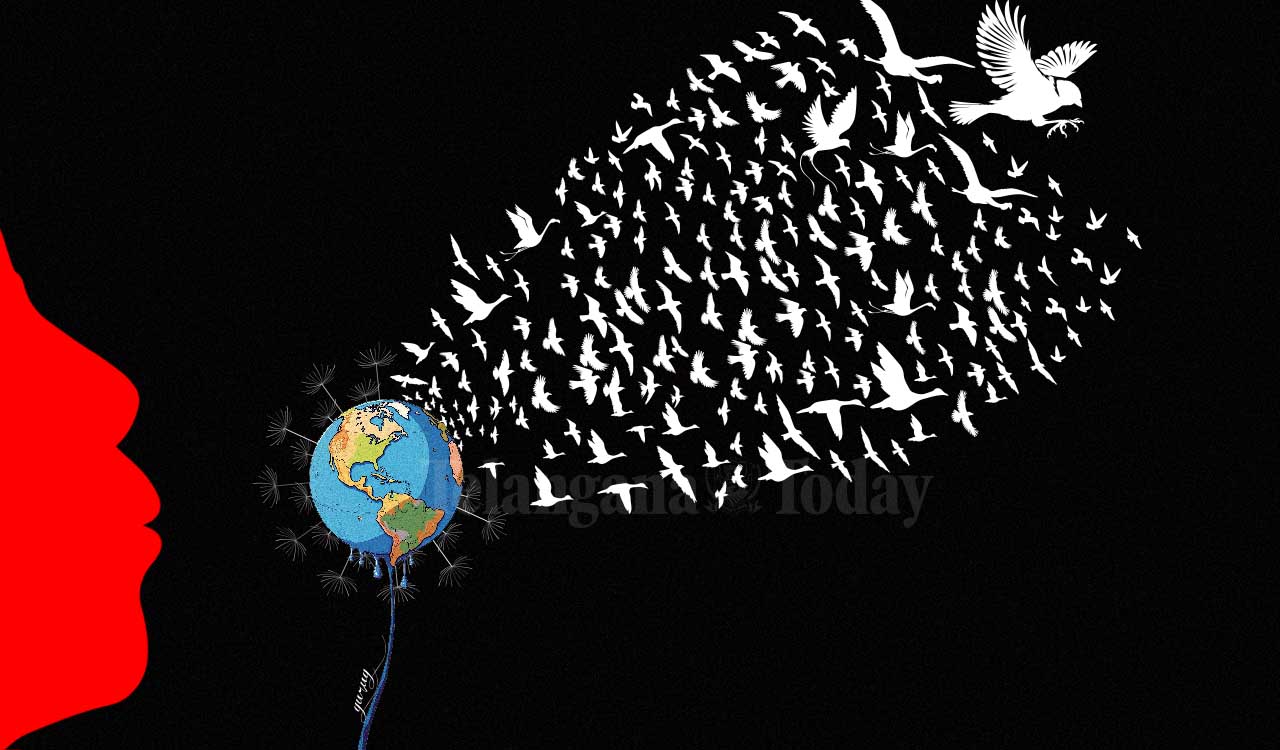

Rewind: Is India fuelling Ukraine war?

Beyond Russian oil, US tariffs on India reveal a deeper strategic rift between Washington and New Delhi in a changing world order

By Dr Anudeep Gujjeti

US President Donald Trump’s trade tactics toward India are not new. Even in his first term, he spoke against India’s high import levies, terming it the “tariff king” and a “big abuser” of tariffs as early as 2019. Fast forward to 2025, and Trump, now in a second term, has reignited the tariff war with India under a new pretext — New Delhi’s purchase of Russian oil.

Also Read

On April 2, 2025, he signed an Executive Order imposing a universal 10 per cent “reciprocal” tariff on virtually all imports. While certain raw materials and critical goods were spared, it set the stage for harsher country-specific measures. After five rounds of fruitless US-India trade talks, Trump abruptly broke off negotiations in late July. Instead of the anticipated deal, on July 30, he announced a punitive 25 per cent tariff hike on Indian goods, calling India’s tariffs “among the highest in the world” and its non-tariff barriers “obnoxious”. The very next day, his rhetoric turned sarcastic, and he called India a “dead economy”.

By August 6, he signed another Executive Order imposing an additional 25 per cent duty on Indian imports, doubling tariffs to 50 per cent and bringing India into the club of most heavily tariffed US trading partners. The White House accused India of “undermining” efforts against Russia by buying oil and even reselling it “on the open market for big profits”.

Trump posted on Truth Social that India “doesn’t care how many people in Ukraine are being killed” and vowed to “substantially” raise tariffs as punishment. The additional levies are set to take effect on August 25.

New Delhi called the move “extremely unfortunate,” noting that “many other countries” also import Russian oil out of economic necessity. India’s Commerce Ministry warned that 50 per cent duties would virtually halt exports to its largest market, imperilling sectors from textiles and gemstones to auto parts. Over half of India’s USD 87 billion in annual exports to the US could be affected, putting Indian firms at a 30-35 per cent cost disadvantage against competitors in Vietnam or Bangladesh.

Is Russian Oil Sanctioned?

Washington’s justification for the tariffs is India’s oil trade with Russia. But a crucial fact is that Russian oil itself is not banned by US or EU sanctions. There is no Western law forbidding India from buying Russian oil. Instead, the US and Europe (G7) have relied on a price cap mechanism — a soft embargo denying Western insurance and shipping if oil is sold above the cap. This “shadow ban” relies on Western corporate compliance, rather than forcing buyers like India to stop purchases directly.

In July 2025, the EU decided to revise its Russian oil price cap mechanism, replacing the fixed USD 60 per barrel cap, originally set in December 2022 by the G7 group of nations, with a floating cap pegged at 15 per cent below the six-month average price of Russian Urals crude. This new cap, lowering the ceiling to USD 47.60, will take effect on September 3, 2025. Canada has announced it will align with this revised cap. The shift signals a tightening of Western measures aimed at constraining Russia’s revenue but not to fully disrupt global oil flows.

The US banned Russian oil imports in March 2022, and the EU followed with an embargo on seaborne crude by the end of that year. But neither imposed secondary sanctions on third countries.

Who’s Funding Russia?

The US claims India’s oil buys are helping Putin’s war, but a closer look at data exposes a selective outrage. Who are the top buyers of Russian energy today? Though China and India top, Europe and even the US quietly remain in the mix. According to the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, China buys about 45 per cent of Russia’s crude oil exports and India about 33 per cent, together absorbing the lion’s share of displaced Russian supply. Other Asian and African importers (Turkey, Vietnam, UAE) play secondary roles.

Yet focusing only on oil paints an incomplete picture. Consider natural gas. Europe slashed its pipeline gas imports from Russia by switching to alternative suppliers, but it has quietly increased imports of Russian Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG). In 2023, the EU was the largest buyer of Russian LNG (49 per cent), ahead of China (22 per cent) and Japan. Europe simply swapped one form of Russian gas for another, a loophole in its sanctions.

By mid-2025, roughly 17 per cent of Europe’s gas supply still came from Russia (via the TurkStream pipeline to the Balkans and LNG shipments), down from almost 40 per cent pre-war but hardly negligible. There are months when Spain or Belgium imports more Russian LNG than India’s entire gas consumption.

Though China and India buy most of Russia’s coal, South Korea and Japan also remain significant customers. In nuclear energy, the West has clearly spared Russia’s exports: The EU purchased over 700 million euros worth of uranium products in 2024, and the US spent about USD 624 million on Russian-enriched uranium. Both depend on the State Atomic Energy Corporation Rosatom’s supplies for many reactors.

Overall trade tells a similar story where the “boycott Russia” narrative is not-so-clear. From January 2022 to early 2025, the EU imported 297 billion euros in Russian goods despite sanctions, while the US imported USD 24.5 billion. Much of this was non-energy commodities (fertilizers, metals, chemicals) that remain untouched by sanctions. For instance, Russia was the EU’s top fertilizer supplier as of Q1 2025, holding over 25 per cent of the EU market. The US even increased Russian fertilizer imports in 2022 to USD 1.27 billion, slightly more than pre-war levels.

India’s Foreign Ministry has flagged this hypocrisy. “It is revealing that the very nations criticising India are themselves trading with Moscow,” Randhir Jaiswal, official spokesperson of the MEA, said, adding that unlike India, such Western trade “is not even a vital national compulsion for them”.

Selective Outrage

Why, then, is India being singled out? The answer lies in political optics and strategic leverage. For the US, India’s neutrality on Ukraine and robust ties with Russia undercut the narrative of a world united against Putin. Western commentators have lambasted India as a “fence-sitter” lacking moral clarity. Think tanks and strategists like Ashley Tellis have criticised New Delhi’s multipolar vision as a “grand delusion”, urging it to firmly side with the West.

Such pressure has grown since the Ukraine war began. European officials have voiced frustration at India’s apparent “fence-sitting” during UN votes. From New Delhi’s perspective, this Western outrage is selective and self-serving. India has consistently called for an end to the war — without harming its economy. This stance is rooted in India’s long-standing doctrine of strategic autonomy.

End to the War

If India stopped buying Russia’s crude oil tomorrow, those barrels would be rerouted to China, Turkey, or others at deeper discounts. Price may spike, but Russia would still find buyers. Europe’s near total oil embargo since 2022 did not force Moscow to surrender; instead, Russia redirected sales to Asia.

Indian officials have repeatedly warned US envoys that without Russian oil, global prices would rise sharply, harming importers. Washington implicitly recognises this — it has not imposed CAATSA (Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act) on India for buying Russian arms such as the S-400 system or oil, despite that law’s provisions, precisely to avoid a rupture with Delhi. The tariff, therefore, appears aimed less at punishing Moscow and more at pressuring India into trade concessions or limits on Russian oil intake.

This clash recalls the Cold War mindset: “you’re either with us or against us.” In the eyes of Trump and some in Washington’s strategic circles, India’s unwillingness to join sanctions or criticise Russia is a loyalty failure, despite India never having made such an alliance commitment. India has, nevertheless, avoided knee-jerk retaliation, keeping channels open for dialogue while quietly slowing new Russian oil purchases.

Autonomy in Multipolar World

India’s approach is consistent: it will partner with the US where interests align, and diverge where they don’t. That is the essence of strategic autonomy, a principle it has held since the Non-Aligned Movement of the 1950s. In the Indo-Pacific, India is tightly aligned with the US and its allies to counterbalance China’s rise, as evident in the Quad security dialogue and expanded defence cooperation, while maintaining ties with Russia for energy security.

With a GDP per capita of only USD 2,500 and millions still in poverty, India has to prioritise affordable energy and economic growth.

A Strategic Gulf

The US tariffs on India may ostensibly be about oil and Ukraine, but they reveal a deeper strategic divide between Washington and New Delhi. This is not a simple tariff game; it is symptomatic of mismatched expectations in a changing world order. The US, especially under Trump, still tends to view international relations in binary terms, where partners are either “with us or against us” while India, with a long memory of colonial subjugation, insists on charting its own course in a multipolar world.

For India, what is at stake is not just access to cheap oil but the principle of an independent foreign policy in the face of great-power pressure. For the US, it’s about sustaining a global coalition against authoritarianism. Both nations profess to desire a strong strategic partnership, especially to counter China. The tariff war has laid bare the need for a more candid dialogue about each side’s red lines and priorities in this “new Cold War”.

Oil Politics

- Neither US nor EU legally prohibit India from buying Russian oil — only a G7 price cap exists

- Soft embargo includes denying Western insurance and shipping if oil is sold above $60/barrel. The EU is now revising the price cap to $47.60, which will take effect on September 3

- According to Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air, India buys about 33% of Russia’s crude exports — second only to China’s 45%

- Trump accuses India of reselling Russian oil “on open market for big profits,” and “fueling the Russian war machine”

- Europe’s oil embargo since 2022 failed make Moscow budge. Instead Russian barrels moved to Asia, mainly India and China

- India warns US that removing Russian oil from its supply would spike world prices

- EU, Japan, South Korea still import other Russian energy forms, while India is singled out

Selective Sanctions

- US imported $1.27 billion in Russian fertilizers in 2022 — more than pre-war

- Europe buys more Russian gas — 17% of Europe’s gas supply comes from Russia despite sanctions

- China and India buy most of Russia’s coal, but South Korea and Japan are also significant customers

- In nuclear energy, the West has spared Russia’s exports entirely: the EU purchased over 700 million euros worth of uranium products in 2024, and the US spent about $624 million

(The author is Assistant Professor, Symbiosis Law School, Pune, and Young Leader, Pacific Forum, USA)

Related News

-

Couple elected as chairperson and vice-chairperson of Nirmal Municipality

3 hours ago -

Telangana municipal polls: BRS pockets 18 municipalities

3 hours ago -

BJP draws sharp criticism for meeting Congress leaders in Hyderabad

3 hours ago -

Inorbit Mall Cyberabad hosts Valentine specials, interactive games and live performances

3 hours ago -

Jangaon chairperson election postponed amid high drama

4 hours ago -

Editorial: Showcasing India’s tech prowess

4 hours ago -

Health Minister orders suspension of absent Jogipet doctors

4 hours ago -

Opinion: India’s new labour codes prioritise capital over labour

4 hours ago