Rewind: Record auctions, missing royalties — Why Artist’s Resale Rights matter

Artists are often left out of the profits their work generates over time. The Artist’s Resale Rights give them a rightful stake in the lasting value of their art

By Dr GR Raghavender

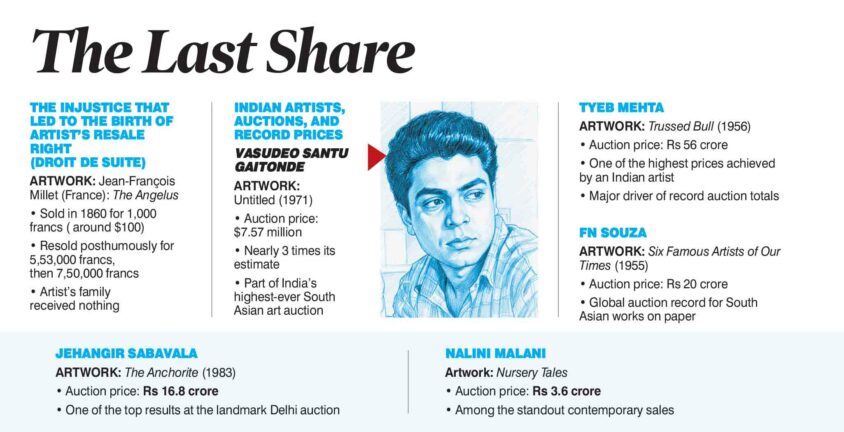

The Artist’s Resale Right, or Droit de Suite (in French), grants visual artists a royalty (a percentage of the sale price) when their original artworks are resold by art market professionals, ensuring they share in their work’s increasing value. In 1860, French painter Jean-François Millet sold his now-iconic masterpiece The Angelus for a modest 1,000 francs, barely $100 at the time. Like many painters of his era, Millet lived and died in poverty, unaware that his work would later become priceless.

Also Read

Fifteen years after his death, The Angelus stunned the art world when it sold for 5,53,000 francs and, just a year later, resold for an even more astonishing 7,50,000 francs. However, while the buyers and resellers grew wealthy, Millet’s own family lived in destitution. This stark injustice sparked a global conversation: should artists or their families benefit when the value of their work multiplies manifold?

Birth of Resale Right

The glaring inequity highlighted by cases like Millet’s pushed the Berne Union to act. In 1948, the Brussels Revision of the Berne Convention, 1886, introduced the droit de suite, or Artist’s Resale Right, in Article 14ter. The provision, based heavily on French property law, guaranteed artists an inalienable right to an interest in any sale of the work subsequent to the first transfer by the author. After the artist’s death, this right could be exercised only by authorised legal heirs or institutions, which own the rights for the duration of copyright.

However, this right comes with a crucial limitation that allows artists’ rights to be claimed only when both the artist’s country of origin and the country of enforcement recognise such rights. This dual requirement of reciprocity has significantly shaped and often restricted the global effectiveness and reach of the

Artist’s Resale Rights

The Resale Rights remain fragmented globally because the provision is optional, not mandatory. While widely enforced in Europe, major markets like the US and China do not recognise them, leading to resales that bypass artists and their estates. Ambiguities in definitions and reliance on national legislation create legal disharmony, and enforcement is hindered by the absence of shared databases, transparency, and monitoring.

Artists’ Resale Rights predate digital art, leaving NFTs (non-fungible tokens)unresolved, and face resistance from auction houses fearing complexity. The system disproportionately benefits established artists, offers little to emerging creators, and suffers from low awareness even where laws exist.

Resale Rights in Visual Arts

In the visual arts, once a work is sold, the artist cannot control its further use. To address this limitation, the Artist’s Resale Right was established as a remuneration right, granting them and their heirs a share of subsequent sales. This mechanism ensures they remain connected to the economic life of their creations and receive fair compensation.

The justification for resale rights rests on social justice: unlike creators in other cultural industries, visual artists lack reproduction or distribution rights. The rights thus prevent them from being disadvantaged compared to peers who benefit from repeated exploitation of their works. It applies specifically to unique originals or limited, numbered editions, reinforcing equity within the art market.

Implementation, however, shapes its impact. In Europe, where harmonisation exists, three examples illustrate its effects:

- Successful artists benefit most, but tapering rates and caps reduce inequities.

- Galleries face challenges, as resale rights could discourage investment in promotion. To balance interests, EU directives allow optional exemptions for resales within three years under euro 10,000.

- Cost allocation matters: If buyers bear artists’ resale rights, auction houses gain an advantage over galleries, and artists may ultimately receive less.

Thus, the rights remain vital yet complex, requiring careful regulation to balance fairness with market dynamics.

Global Campaign

The Artist’s Resale Right is now recognised in around 80 countries. Visual artists are calling for its universal application. The International Confederation of Societies of Authors and Composers (CISAC), the world’s leading network of authors’ copyright societies, has been continuing its global campaign for the universal adoption of the Artist’s Resale Right in 2025.

India introduced its version of resale rights in Section 53A of the Copyright Act, 1957, granting artists (or their heirs) a share in the resale of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and original manuscripts, when the resale value exceeds Rs 10,000. However, the provision remains largely on paper

After last year’s decline, the visual arts sector has returned to growth, with CISAC’s Global Collections Report 2025 recording euro 219 million in collections, a modest but encouraging 0.9 per cent increase. This recovery underscores the resilience of collective licensing systems that safeguard fair remuneration for visual artists.

The report highlights the United Kingdom’s leading role, where euro 14 million in royalties were collected, nearly one-third of the euro 49 million global total, cementing the UK as the top collecting country. This success reflects the strength of the UK’s Artists’ Resale Rights framework and its effective administration by Design and Artists Copyright Society (DACS) and other collective management organisations.

Legal Frameworks

Effective implementation of the Artist’s Resale Right requires practical support in three key areas: data, compliance, and legal frameworks. Reliable sales data is essential, yet estimates of the global art market vary widely, underscoring the need for transparency. Cost-effective online reporting systems that allow professionals to upload transactions and enable artists to track resales would strengthen monitoring and royalty collection.

Compliance remains a challenge, as many secondary sales are underreported, making enforcement difficult. Awareness among artists and market participants is crucial, particularly in regions with emerging collective management organisations. Legally, the resale right is inalienable, lasting for the artist’s lifetime and up to 70 years after death. Ongoing debates concern transferability, responsibility for payment, royalty rates, and calculation methods. Policymakers must refine systems to ensure fair, efficient application worldwide.

India’s Attempt: A Good Law Left Dormant

India introduced its version of resale rights in Section 53A of the Copyright Act, 1957, granting artists (or their heirs) a share in the resale of paintings, sculptures, drawings, and original manuscripts, provided the resale value exceeds Rs 10,000. The law empowers the commercial bench in the high courts to fix royalty rates capped at 10 per cent of the resale price and adjudicate disputes. In theory, Section 53A offers strong protection.

In practice, the resale share right in India remains largely ineffective due to the absence of operational rules, a dedicated copyright society, and clear guidelines on royalty rates or procedures. The highly informal nature of the art market, lack of mandatory disclosure of resale details, and poor awareness among stakeholders further hinder implementation. With no reciprocity arrangements for international enforcement and no supporting case law or government action, the provision exists mostly on paper rather than in practice.

Leaving Artists Behind

While legal provisions stagnate, the Indian art market is experiencing a remarkable surge. At a recent Saffronart auction in Delhi, the market achieved a historic milestone. A 1971 untitled painting by Vasudeo Santu Gaitonde sold for $7.57 million, nearly three times its estimate — part of a record-breaking $40.2 million (Rs 355.8 crore) sale, the highest-ever for South Asian art. This auction set several notable benchmarks in the art market, led by Tyeb Mehta’s Trussed Bull (1956), achieving an impressive Rs 56 crore. FN Souza’s Six Famous Artists of Our Times (1955) followed with Rs 20 crore, marking a global auction record for South Asian works on paper, while Jehangir Sabavala’s The Anchorite (1983) reached Rs 16.8 crore.

Contemporary art also made its mark, with Nalini Malani’s Nursery Tales fetching Rs 3.6 crore, underscoring the breadth and depth of demand across generations. These numbers reflect a maturing Indian art ecosystem but also spotlight the silence around resale share royalties. If Section 53A in the Copyright Act, 1957, were effectively implemented, Indian artists and their families could participate meaningfully in the wealth generated by soaring valuations.

Reform, Awareness, and Technology

At this juncture, India stands at an important crossroads. With the art market booming, the need to strengthen resale share rights has never been more urgent. Strengthening the resale share right in India requires clear implementation rules, a dedicated copyright society to be registered by the visual artists, and mandatory disclosure of resale information by market players.

Despite soaring prices, artists and their heirs receive no share of resale profits due to weak enforcement of resale rights. Legally, the resale right is inalienable, lasting for the artist’s lifetime and up to 70 years after death

Digital registries potentially using blockchain should be created to track provenance and secondary sales, supported by national awareness campaigns for artists. International reciprocity in the Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and active collaboration among galleries, auction houses, collectors, and artists are essential to build a transparent, technology-driven framework for effective enforcement.

On the path to Viksit Bharat, tragedies like Millet’s must not be repeated in our times. Indian artists, who shape the nation’s cultural landscape, too often remain excluded from the financial rewards their creations later command. Resale share rights restore a measure of justice, enabling creators to share in the enduring value of their work. India already possesses both the law and the market; what is needed now is decisive action to make these rights truly effective.

A flourishing artistic economy cannot afford to leave its artists behind. By reforming and activating resale share rights, India can ensure that future Gaitondes, Souzas, Mehtas, and countless emerging talents receive the recognition and reward they so rightly deserve.

(The author is an Intellectual Property Law and Technology expert, Senior Consultant in Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade [DPIIT], Ministry of Commerce and Industry, and retired Joint Secretary, Government of India; Former Registrar of Copyrights. Views are personal)

Related News

-

Editorial: Delays hampering key science project

7 hours ago -

Opinion: Beyond misclassification: Recognising dignity, opportunity for DNTs

8 hours ago -

Union Minister Raksha Khadse stresses role of sports journalism

8 hours ago -

India topple Italy 1-0 to enter FIH Hockey World Cup Qualifier final

8 hours ago -

HCA funds: Telangana Cricket Association alleges fraud

8 hours ago -

Soukouna’s late goal gives Rajasthan United their first win of IFL 2025-26

8 hours ago -

Indian boxers assured of five medals in World Boxing Futures Cup

8 hours ago -

Two Indians killed in attack in Oman’s Sohar amid West Asia tensions

8 hours ago