Breaking the Box: Classical Dance beyond gender

Though India’s cultural and spiritual heritage is replete with powerful male dancers whose legacies are foundational to classical dance, today when a young boy shows interest in this art form, he is often met with discouragement or derision

By Sarani Oddiraju

For centuries, rigid gender roles have shaped how individuals express themselves. Though progress has been made, many stereotypes persist – particularly when it comes to boys pursuing classical dance. The moment a young boy shows interest, he is often met with discouragement or derision: “That’s for girls,” or “Why not try sports instead?”

These attitudes are not only outdated – they are deeply ironic. India’s cultural and spiritual heritage is replete with powerful male dancers whose legacies are foundational to classical dance itself.

Dance and Divinity: A Sacred Legacy

In Indian mythology, dance is not merely an art form — it is a cosmic force. Lord Shiva, in his form as Nataraja, performs the Tandava, a dance symbolising the rhythm of creation and destruction.

Ancient Tamil texts like Koothanool, authored by Sathanar, describe a divine dance duel between Shiva and Goddess Uma, where Shiva ultimately triumphs — affirming not only his mastery but the central role of male dancers in the classical tradition.

The sage Bharata Muni, who compiled the Naṭyasastra – the foundational treatise on Indian performance arts – was himself a man. Iconic figures such as Krishna, known for his graceful Raasleela, and Ganesha, worshipped as Narthana Ganesha in temples like Marundeeswarar in Chennai, further reflect the sacred male presence in dance.

Historically, many classical dance forms were performed and preserved by men. Kathakali was once an all-male art form, with performers portraying both male and female roles. Kuchipudi originated as a dance-drama tradition taught exclusively to Brahmin boys by Siddhendra Yogi.

Modern Barriers in a Historical Art

KP Rakesh, a Bharatanatyam dancer, choreographer, nattuvanar and teacher based in Chennai, reflects on his early experiences: “I began learning dance at age 8 through school co-curricular activities. My first performances were during annual day events, and those moments sparked a lifelong connection to the art.”

KP Rakesh, a Bharatanatyam dancer, choreographer, nattuvanar and teacher based in Chennai

Now a faculty member at Kalakshetra, one of India’s most respected dance institutions, Rakesh acknowledges the societal gap: “Schools still fall short in encouraging boys, largely due to peer teasing and stereotypes. However, dedicated dance institutions provide a much more supportive environment. I’ve seen boys thrive when given the right space. But early encouragement is essential to normalise classical dance for boys.”

Resistance and Resilience

In Hyderabad, Kuchipudi dancer and Carnatic musician Dandibhotla Srinivasa Venkata Sastry, fondly known as DSV Sastry, offers a candid take on public perception: “People will say what they want. One shouldn’t care about the words of the wind. If a child loves dance, he will continue, no matter what others think.”

Kuchipudi dancer and Carnatic musician Dandibhotla Srinivasa Venkata Sastry

He also critiques the persistent stereotype that links male dancers with sexual orientation: “This misconception arose only in the last hundred years — that if a man dances, it will affect his identity. However, not everyone who dances shares the same personal traits, and not everyone with those traits is a dancer. These are immature, baseless ideas.”

Recalling cultural shifts, Sastry adds: “In our Telugu States, we grow up loving cinema. When Sagara Sangamam was released, everyone wanted to dance like Kamal Haasan. These trends will come and go, but we dance for those 10 to 15 per cent who truly value the art and for ourselves.”

Cultural Bridges on Global Stage

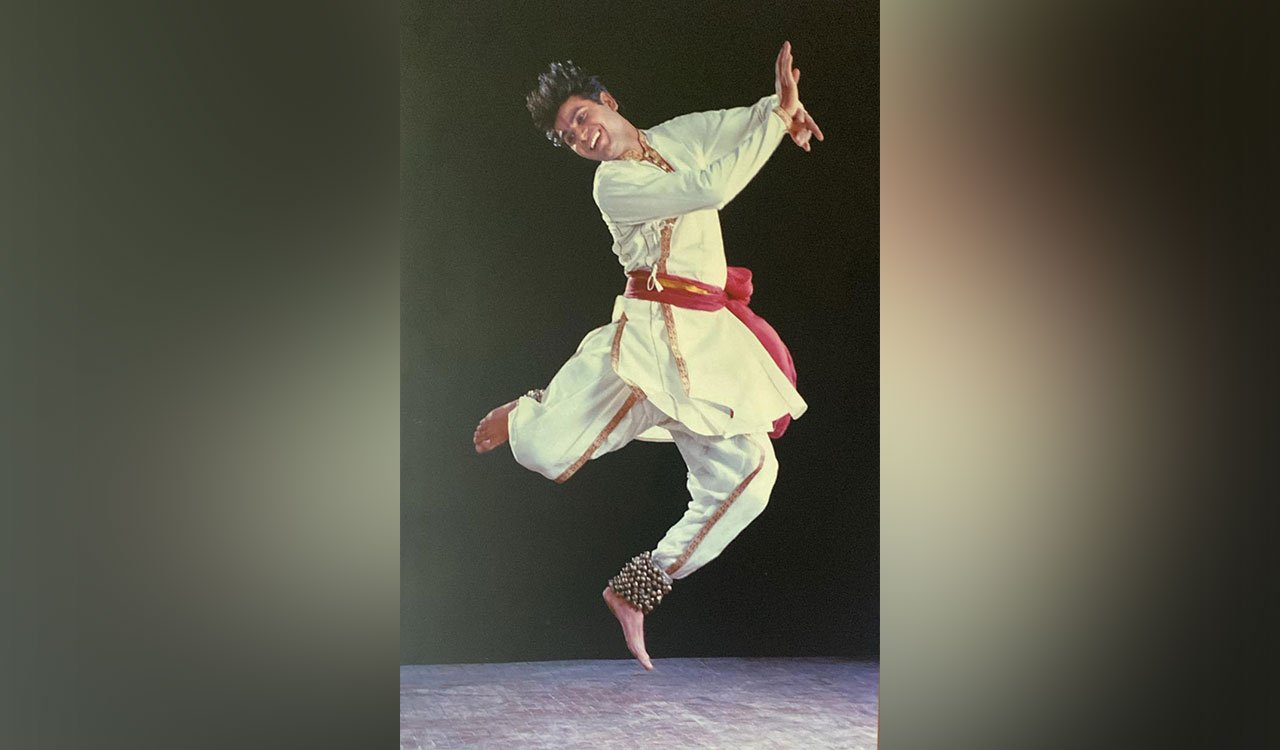

Hemant Panwar, a Kathak dancer and musician practising the Jaipur Gharana, has spent the past two decades nurturing Indian classical dance among diaspora communities.

“In ancient Bharat, everyone danced – Shiv and Shakti, Krishna and Radha. It was the invasions that brought about the idea that only women should dance,” says Panwar now based in Canada.

Panwar’s family reflects this cultural split. While some relatives became musicians, others became farmers – yet he, son of a farmer, chose to follow dance.

Narrating an incident from his early years, he says: “I would travel with my ghungroos (bells) on the bus, and people would ask, ‘Oh, you dance? But what else do you do?’ Many still don’t view dance as a legitimate profession.”

For his first 10 years in Canada, not a single boy enrolled in his classes. Determined to change this, he reached out to temples, emphasising the importance of both male and female energies in dance. “A priest eventually said, ‘Here, take my son and teach him.’ I conducted a workshop for 25 boys and told them, ‘If you don’t like it, you can leave.’ But they stayed — and just recently performed a Ramleela production after five years of hard work”.

The Final Step Forward

Dance demands discipline, devotion, and soul – qualities that transcend gender. The personal journeys of these artistes reveal not just the barriers but also the breakthroughs that come with embracing tradition, challenging prejudice, and fostering inclusivity.

It’s time to return to our cultural roots and move forward with open minds. Every child, regardless of gender, deserves the freedom to explore the stage and express through movement. Let us dismantle the boxes we’ve built and let all dancers take their rightful place under the spotlight.

(The author is Diploma Holder from Kalakshetra and is pursuing Masters in Bharatanatyam from University of Madras)

Related News

-

Hospital sewage fuelling antibiotic-resistant bacteria in Hyderabad drains: Study

12 mins ago -

Bengaluru, Delhi-NCR account for over half of India’s AI job openings: Report

38 mins ago -

Hoax bomb threat emails trigger panic in Telangana and Andhra courts

51 mins ago -

‘Never thought he would do this’: Neighbour reveals chilling details in Indore MBA student murder case

1 hour ago -

Grokepedia an unrealistic idea that won’t work: Wikipedia Co-founder at AI Summit

1 hour ago -

ECI announces Rajya Sabha polls for two Telangana seats

1 hour ago -

Galgotias University, under fire over Chinese robodog, asked to leave AI Summit

1 hour ago -

Sabarimala gold theft case: Tantri Rajeevar gets bail, 6th accused to secure release

2 hours ago