From Bharatanatyam to Kathak: The maths behind the movement

Indian classical dance is not just an aesthetic expression — it is a blend of rhythm, geometry and precision, woven into every graceful movement

By Sarani Oddiraju

Mathematics – the very word may evoke memories of school lessons and complex equations. Yet, as ancient Indian knowledge systems remind us, maths is not confined to classrooms. From the Vedas to daily rituals, mathematics has been seamlessly woven into Indian culture. The Rig Veda mentions geometry and even early concepts of π (pi), the Yajur Veda discusses large numbers and infinity, while the Atharva Veda introduces the idea of shunya (zero).

Despite this deep-rooted connection, many still see maths and the arts — particularly dance — as unrelated worlds. What most spectators miss is the rigorous mathematical precision behind every expressive gesture or rhythmic beat on stage. Indian classical dance, far from being just aesthetic and emotive, is grounded in numerical patterns, rhythmic cycles and spatial geometry.

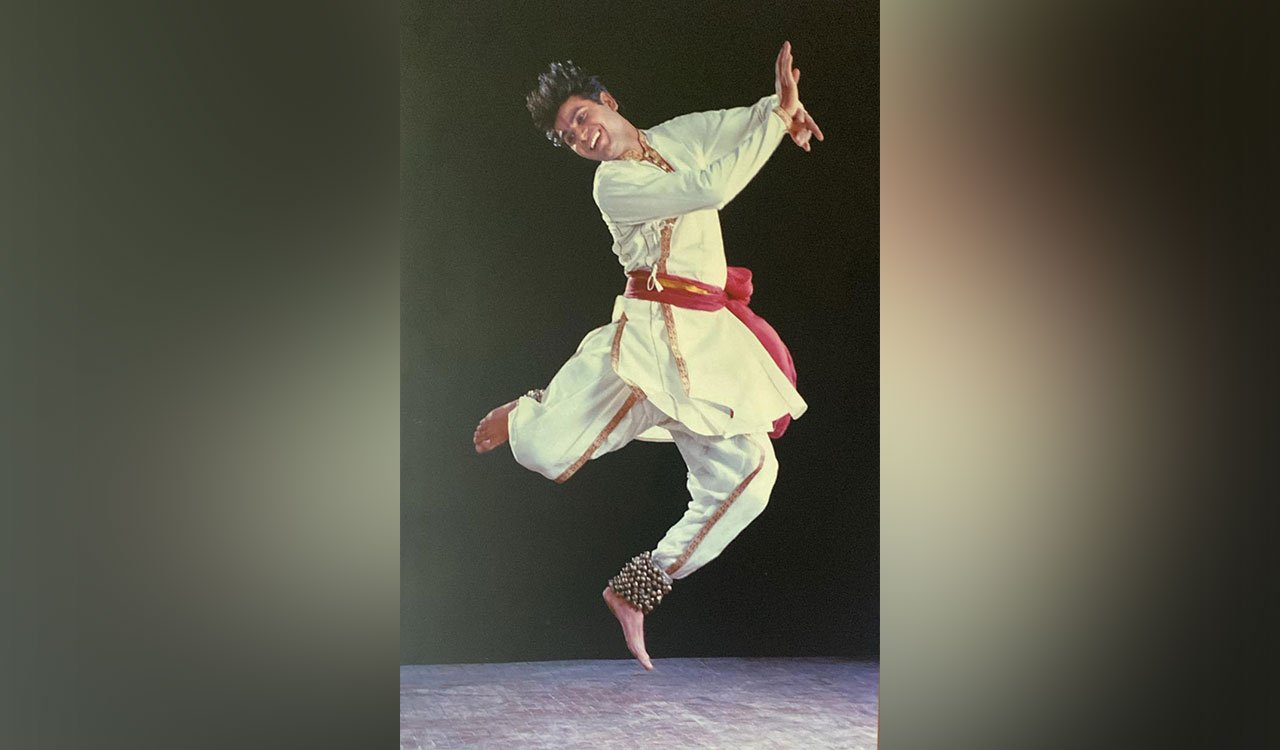

Kathak: Rhythm, Ratios, and Recitation

For dancer Vibha Dubey, rhythm isn’t just something you feel, it’s something you calculate, compose, and command with precision. Dubey has been learning Kathak (Lucknow Gharana) since 1999. What began as a childhood hobby in Varanasi turned into a lifelong passion. With her Bachelor’s degree and Masters in Kathak, she continues her journey under the guidance of Professor Ranjana Srivastava, former Dean, Faculty of Performing Arts, BHU, and performs.

“People think Kathak is only about grace and expression, but it’s filled with calculations. Every piece is a puzzle of time and rhythm,” says Vibha who is also the founder of Vibha’s Kathak Nritya Academy in Kondapur, Hyderabad.

Kathak compositions are (Brandish) built around taals, rhythmic cycles like Teen Taal (16 beats) or other cycles with 8, 10 or 12 beats and the bols (Tabla syllables) which dancers must internalise. Each movement must fit perfectly into these frameworks, requiring dancers to compress, stretch, double, or halve their steps with mathematical precision. “It’s about squeezing or expanding within a fixed time which is exactly what maths teaches us,” she says.

One of the most unique elements of Kathak is Padhant (means Padhana), the spoken recitation of the rhythmic syllables (bols) before dancing them. “The dancer herself does this, clapping to mark the taal. It’s maths in sound and movement,” she says.

Bharatanatyam: Angles, Permutations, and Precision

Dr Radhika Vairavelavan, founder of Chathur Lakshana Dance School in Chennai, has been learning Bharatanatyam since the age of three. A student of Ambika Buch, retired professor from Kalakshetra Foundation, Radhika combines her deep knowledge of Bharatanatyam with an academic background in physics – holding degrees from institutions such as Kalakshetra Foundation, Kalai Kaviri College of Fine Arts, Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning, and Bharathiar University.

“To think that knowledge in India exists in silos is a mistake,” she says. “Dance is not merely entertainment – it is communication, science, and philosophy in motion.” She points out that classical dance has the potential to convey scientific and technical ideas, highlighting Antariksha Sanchar – a production based on the Vaimanika Shastra, an ancient text exploring aerodynamics and aircraft-like machines.

The production, led by Jayalakshmi Eshwar, an alumna of Kalakshetra and recipient of the Sangeet Natak Akademi award, offered a creative interpretation of these concepts. “Such ideas, including those about motion, velocity, and structure, can be interpreted through dance. It shows how capable Indian classical dance is of expressing even scientific knowledge,” she says.

Dr Vairavelavan says even the most basic posture in Bharatanatyam, Aramandi, reflects geometry. “The stance requires dancers to lower themselves to half their height, align their spine, and find their centre of gravity. That’s simple physics.” Movements across angles and lines, such as a hand moving diagonally, are all measured by precise angular placements. The visual harmony we admire on stage is no accident; it is mathematical accuracy made beautiful.

When practising Adavus (basic foundational steps), dancers use three different speeds:

• 1st speed: 1 beat = 1 step

• 2nd speed: 1 beat = 2 steps

• 3rd speed: 1 beat = 4 steps

In compositions called Jathis and Korvais, dancers explore permutations and combinations of rhythmic patterns. “This is where Prasthara comes in – calculating how different steps can be grouped, sequenced and executed within a fixed cycle. We fractionalise counts and mentally track them using what we call Kannaku,” Radhika explains.

Mohiniyattam: Circles, Spirals, and Sequences

Kalamandalam Kavitha Krishnakumar, an acclaimed Mohiniyattam artiste, choreographer and recipient of the Kerala Sangeetha Nataka Akademi Award, says numbers are inseparable from the art. With a diploma, degree, and MA from Kerala Kalamandalam, Kavitha has spent over 35 years in the field.

“Every beat, every movement has rhythm — and rhythm is maths. Even walking to the door when a bell rings, it involves rhythm and sequence. That’s mathematics in motion. In dance, these patterns become precise and purposeful,” she says.

The form draws its rhythmic structure from Carnatic music, with talams like Adi, Rupaka, and Cāpu guiding every step. The opening piece, Cholkettu, sets the tempo with carefully composed rhythmic syllables (chollu), performed in a slow tempo (vilamba kaalam), like a lyrical equation unfolding.

But it’s not just rhythm, it’s also shape. “Our body draws lines and curves,” Kavitha says. Meyadavus (limb movements) and chuzhups (spirals) follow arcs, circles and parabolas, giving Mohiniyattam its signature fluidity.

The Varnam, often the most complex item, increases the speed of movements while keeping the lyrics steady. Dancers must master this thrikaala jathi, a three-speed sequence, purely through motion.

In the final piece, Thillana, the dancer navigates five rhythmic modes (nadais); tiśram, chatusram, khaṇḍam, miśram, and saṅkīrṇam which are crafted into intricate Korvais (sequences) and Yathis (structural designs).

“Mohiniyattam is about blending complexity with softness,” Kavitha says. “Every graceful curve conceals calculation. That’s the beauty of it, maths hidden in motion.”

When Numbers Speak Through Movement

Indian classical dance is more than art, it is a live demonstration of the synergy between emotion, rhythm, physics, and mathematics. From beat cycles and body alignment to structured improvisations, dancers must think like mathematicians even as they move like poets. Perhaps it’s time we acknowledge, behind every graceful spin and rhythmic footwork lies a silent, elegant equation.

(The writer is a Diploma Holder from Kalakshetra and is pursuing Masters in Bharatanatyam from University of Madras)

Related News

-

Sabarimala gold theft case: Tantri Rajeevar gets bail, 6th accused to secure release

6 mins ago -

Gold chain snatched near CM’s residence in Jubilee Hills

6 mins ago -

Delhi courts Dhaka after BNP sweep, keeps close watch on ISI moves

16 mins ago -

Manjeera Pipeline Burst: Water restored in Manikonda within 24 Hours

18 mins ago -

Dark-web syndicates wage low-cost war on Indian judiciary

32 mins ago -

Andhra horror: Suspect in minor girl’s rape, murder found dead

1 hour ago -

Bandh observed in Kyathanpalli; heavy police deployment at Balka Suman’s residence

1 hour ago -

Four children suffer burns after drum filled with chemicals explode in Bengal’s Canning

1 hour ago