Opinion: Growing uncertainty and impact on India’s Balance of Payments

India should focus on expanding trade with developed countries rather than developing nations, leveraging its skilled and cost-effective labour advantage

By Dr Kedar Vishnu, Ajitesh Menon, Ganesh R Kulkarni

Since the 1980s, globalisation has expanded rapidly, driven by technological advancements. It grew further in the 21st century through increased trade, investment and migration. However, the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic significantly challenged its advancement. Over the last decade, many policymakers have questioned the benefits of globalisation for developing countries.

The disparity between the rich and the poor has widened significantly over the past two decades, along with a growing gap between developed and developing nations. Are developed countries primarily focused on capturing markets in developing nations, or are they genuinely helping improve these nations’ manufacturing sectors and boost their productivity? Global market uncertainty has further escalated due to the ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, as well as the protectionist policies under President Donald Trump who has unleashed a tariff war.

Many economists remain uncertain about Trump’s economic policies and how they would affect developing nations. Amid rising global uncertainty, it is crucial to examine how India’s Balance of Payments (BoP) has been influenced, especially in the post-Trump era. Based on the RBI’s Q3 BoP data released on 31 March 2025, we examine how much this uncertainty has affected India’s trade performance.

External Sector

India’s current account has experienced notable fluctuations over the years. The country had modest current account deficits (CAD) in the late 1990s and early 2000s. However, beginning in 2004-05, deficits increased significantly, peaking at $-88.2 billion in 2012-13 due to growing trade imbalances and increased import prices.

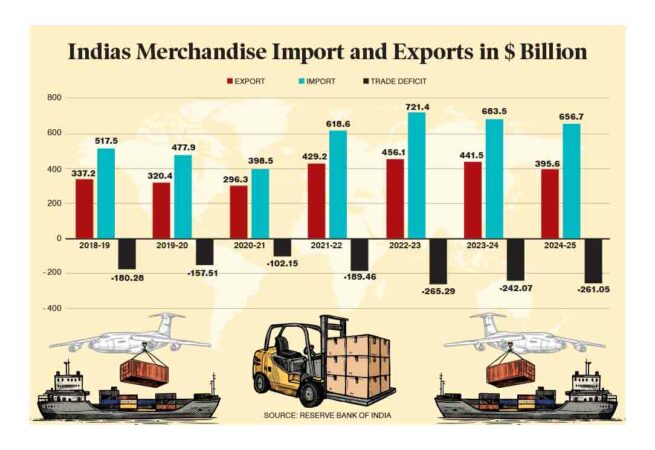

After a slight improvement in the middle of the decade, rising global uncertainties, currency depreciation and high import costs caused the deficit to surge again in 2018-19 ($-57.3 billion) and 2021-22 ($-38.8 billion). Due to a significant drop in imports during the Covid pandemic, there was a surplus of $23.9 billion in 2020-21; however, the imbalance resurfaced in subsequent years. From April to December 2024, CAD stood at $-37.1 billion, primarily driven by a high merchandise trade deficit. (see infographics). This shows that imports are rising faster than exports, particularly crude oil and other inputs.

India’s services trade surplus increased from $82 billion in 2018-19 to $162 billion in 2023-24 but declined to $171 billion in 2024-25 (April-February 25). The surplus was mainly due to IT and business process outsourcing services. The growth in the trade surplus reflects India’s competitive edge in services, which helps offset the deficit in merchandise trade.

FDI decreased drastically to $ -2.31 billion in Q2 and $ -2.77 billion in Q3, suggesting growing investor concerns about policy stability and long-term prospects, after being strong at $6.64 billion in Q1 of 2024-25

The capital account showed a robust surplus of $87 billion in FY 2023-24, reflecting strong foreign investment inflows and investor confidence. However, in FY 2024-25 (April to Feb data), it declined to $22.7 billion — a staggering 73.9% contraction and the lowest level during this period. Regretfully, FDI decreased drastically to $-2.31 billion in Q2 and $-2.77 billion in Q3, suggesting growing investor concerns about policy stability and long-term prospects, after being strong at $6.64 billion in Q1 of 2024-25.

The inherent volatility of short-term capital was shown by the portfolio investment, which rose from $0.945 billion in Q1 to $19.85 billion in Q2, before experiencing a steep outflow of $ -11.37 billion in Q3. The steep drop in FDI inflows raises questions about India’s long-term investment climate and could be caused by sector-specific restrictions, geopolitical risks or regulatory uncertainty.

Trump’s Leadership

Understanding how trade dynamics will change when Trump introduces a reciprocal tariff for India is crucial. India recorded a trade surplus of $45.66 billion in 2024, with exports to the US totalling $87.42 billion and imports amounting to $41.75 billion. In Feb 2025, India’s trade surplus was $4.85 billion, with $8.35 billion in exports and $3.50 billion in imports. Trump is focusing on reducing the trade surplus from India.

Trump’s reciprocal tariffs violate several WTO norms. He has questioned several international trade theories developed by renowned economists, including Paul Krugman’s New Trade Theory, David Ricardo’s Comparative Advantage, Eli Heckscher and Bertil Ohlin’s Heckscher–Ohlin Model, and Adam Smith’s Absolute Advantage. All international trade theories, both theoretically and empirically, demonstrate that international trade benefits all countries and enhances individual welfare over time.

Mitigating Impact of Uncertainty

WTO regulations permit member nations to safeguard vulnerable industries, especially those connected to rural employment and food security.

India should focus on expanding trade with developed countries rather than developing nations, leveraging its skilled and cost-effective labour advantage. It should speed up the completion of free trade agreements with the UK and the European Union. Companies seeking to diversify their supply chains away from China should be drawn to India as a competitive manufacturing powerhouse. Expanding the industrial sector is another reason India and the US should work together more closely.

Thus, India needs to have a strategic relationship with the US. New Delhi should also create a proper institutional structure to handle financial, technological, trade and investment ties.

(Dr Kedar Vishnu is Associate Professor, and Ajitesh Menon and Ganesh R Kulkarni are students of Economics & Political Science, at Manipal Academy of Higher Education [MAHE], Bengaluru)

Related News

-

Modi, Macron vow deeper defence, trade partnership

9 hours ago -

Sports briefs: Dharani, Tapasya clinch honours

9 hours ago -

Man arrested for cultivating ganja plants in Telangana’s Adilabad

9 hours ago -

Second successive win for Titans in Samuel Vasanth Kumar basketball

9 hours ago -

Women councillors allege misconduct by Congress in Kyathanpalli

9 hours ago -

Gauhati Medical College doctor lodges FIR alleging harassment by principal

9 hours ago -

Two FIRs filed in Chikkamagaluru after week-long stone pelting on house

9 hours ago -

Viral video shows SUV hitting biker in Dwarka, teenage driver detained

9 hours ago