Opinion: The quiet crisis of accountability in India’s democratic institutions

It’s not just the corruption of individuals, but the corrosion of institutions that frightens Indians abroad

By Dr Raghu Chaliganti

As part of the Indian diaspora, I follow my homeland with love, pride, and increasingly, with deep worry. India often presents itself to the world as the world’s largest democracy, an emerging economic powerhouse, and a nation that inspires confidence. But behind this proud façade, institutions, the very backbone of democracy, are crumbling under the weight of corruption, political capture, and silence.

Also Read

The recent revelation that ten virtually unknown political parties in Gujarat received Rs 4,300 crore in donations is not just a story about money. It is a story about institutional decay. These parties barely exist in the public eye, fielding only a handful of candidates, and have no genuine grassroots support. Yet, they became channels for staggering sums of money, dwarfing the resources of many mainstream political forces (Times of India, 2025).

ECI Looks Away

Where is the Election Commission of India (ECI), once celebrated globally as a fearless guardian of democracy? Instead of standing firm, it appears to look away. Instead of protecting the voter, it shields the powerful. If the ECI cannot ask basic questions about such blatant financial distortions, then who will? (National Herald India, 2025).

And what about the judiciary? For decades, the Indian judiciary was held in high esteem, even seen as the last line of defence for the Constitution. But today, it too is increasingly viewed with suspicion. Allegations of bias, delayed justice, selective activism, and even whispers of corruption have tainted its credibility (Human Rights Watch, 2025). How can the Supreme Court and High Courts remain silent when democracy itself is under assault? If they will not act on matters of such grave public interest, who will act?

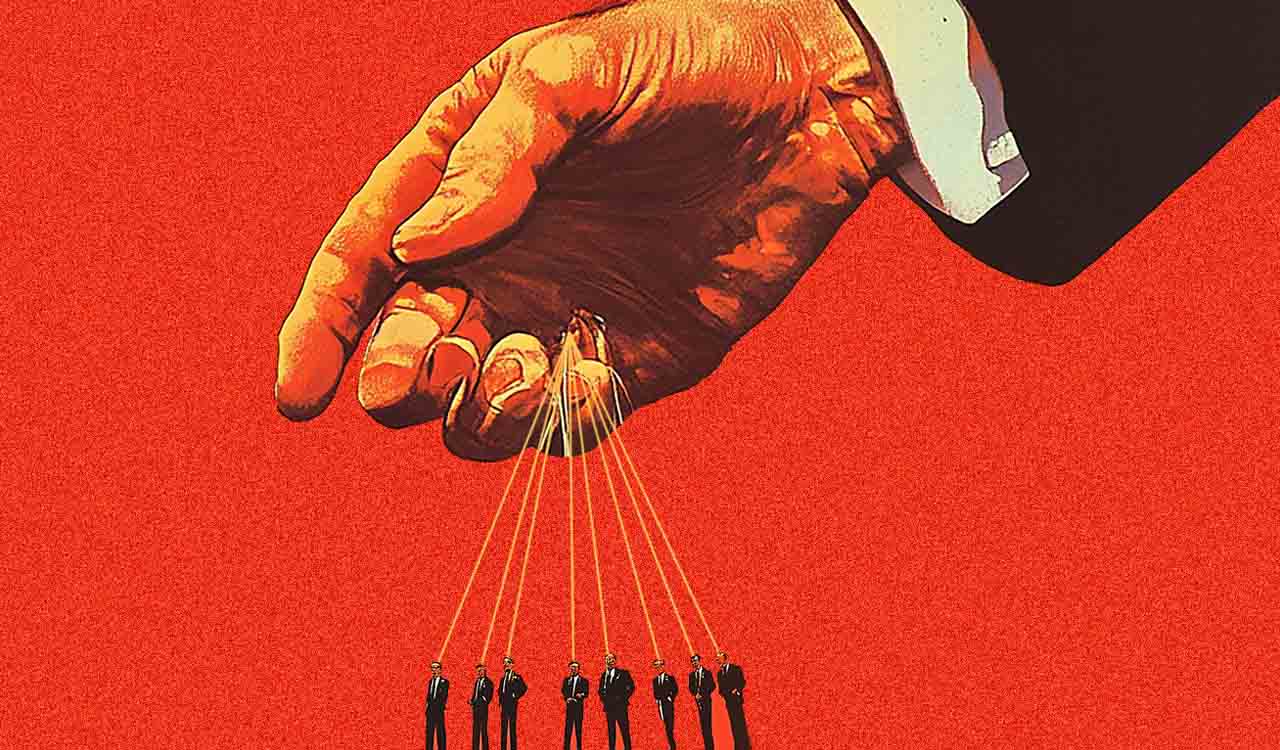

This is what frightens Indians abroad — not just the corruption of individuals, but the corrosion of institutions. A corrupt politician can be voted out. But when the institutions — the courts, the regulators, the watchdogs become compromised, democracy itself becomes hollow. At the same time, the leader of the opposition is on the streets leading a Voter Adhikar Yatra, raising questions about electoral irregularities and the very integrity of India’s democratic system.

Money-Politics Nexus

At the heart of this decay lies the nexus of money and politics, with powerful financial and business interests pumping resources into shadowy parties that exist only as shells. Instead of serving farmers, workers, and the poor, these networks now serve as pipelines of political funding. Governance becomes hostage to money power, while development and social justice are left behind (Freedom House, 2025).

The diaspora watches with unease. We see India rising economically, yet sinking morally. We see political leaders boast of reforms, yet institutions rot from within. We see courts lecture on minor issues, yet remain blind to systemic failures. This duality makes us anxious. How long can India sustain its democratic promise if its institutions are no longer independent? How long before citizens lose faith entirely? The Indian diaspora has always been one of India’s greatest ambassadors, projecting its democratic values to the world.

India’s global reputation will not rest only on GDP figures or technology hubs, but on the strength and honesty of its institutions

But today, we are forced to ask uncomfortable questions: Who exactly controls these anonymous political parties receiving thousands of crores, and what interests do they serve? If the Election Commission, entrusted with protecting democracy, remains silent on blatant financial irregularities, what message does that send about the sanctity of our elections? How can citizens retain faith in the judiciary when it seems hesitant or slow to act on matters that threaten constitutional governance?

What systemic reforms are urgently needed to restore institutional independence and prevent the corruption of democracy through covert funding? In a democracy where institutions falter, how can we ensure that ordinary voters, the farmers, workers, and marginalised, are not further disenfranchised?

Stealing Democracy

How can the diaspora engage and advocate for transparency and accountability in India’s governance? Is India’s global reputation sustainable if political influence increasingly depends on hidden financial networks rather than merit and public support? What role can civil society and media play in breaking the culture of silence and impunity around electoral finance malpractices?

We know that India has long struggled with vote-buying policies, where short-term giveaways and inducements were used to influence voters. But now this has transformed into something far more alarming: vote-robbing. This is not about wooing the voter with freebies. It is about stealing democracy itself, using financial opacity, shell parties, and institutional silence to subvert the electoral process.

What makes this even more disturbing is that it is happening in an age of electronic voting, when transparency and accountability should be stronger than ever. Instead, the Election Commission has failed to answer several critical questions about the integrity of the process, the handling of political finance, and the safeguards meant to protect the sanctity of the vote (Brookings Institution, 2019).

India cannot afford this path. A democracy without credible institutions is a democracy in name only. The poorest and weakest will suffer most, as power and money dominate unchecked. For the diaspora, the message is clear: India’s global reputation will not rest only on GDP figures or technology hubs, but on the strength and honesty of its institutions. If corruption and institutional decay continue, India’s rise will be built on sand.

The time has come for accountability. The time has come for India’s institutions to reclaim their independence and integrity or risk losing the faith of both citizens at home and millions abroad who still want to believe in the idea of India.

(The author is Research Scholar, Fraunhofer Institute, and Founder Chairman, Telangana Association of Germany)

Related News

-

Bengal SIR: Final voters’ list to be published today, classified under 3 categories

-

Opinion: India’s paraquat paradox, a poison still within reach

-

Decision will be taken on plea to hold single phase polls in Tamil Nadu: CEC Gyanesh Kumar

-

Opinion: Modi in Jerusalem signals India’s strategic autonomy in a shifting West Asia

-

Harish Rao demands SIT probe into Bhu Bharati portal irregularities

36 mins ago -

Iran retaliates with missile attack on US 5th Fleet headquarters in Bahrain

45 mins ago -

Iran fires missiles at Israel amid escalating regional conflict

1 hour ago -

Malankara Orthodox Church welcomes Prime Minister’s stand on undivided Church

2 hours ago -

Indians in Iran urged to stay indoors after joint US-Israel strikes

2 hours ago -

Temple hosts community Iftar on its courtyard in Kerala’s Kasaragod

2 hours ago -

Godavari water lifting starts at Nandi pump house under Kaleshwaram project in Karimnagar

2 hours ago -

POCSO case registered against residential school owner, wife in Karnataka

2 hours ago