Opinion: Should extinct species return? Ethics and realities of de-extinction

Reviving lost species may help restore ecosystems, but it demands robust scientific oversight to ensure responsible use

By Tej Singh Kardam

Resurrection, generally known as de-extinction, aims to reverse the extinction of animals by creating new versions of lost species. The goal is to create functional equivalents of extinct species, resulting in ecological enrichment and the restoration of biodiversity and ecosystem functions lost through extinction. Put simply, resurrection science seeks to one day literally bring extinct species back from the dead.

How Does it Work

De-extinction works mainly through three technologies: cloning, genome editing and back breeding. Cloning involves extracting DNA from preserved remains of an extinct species — such as fossils or museum specimens — and inserting it into the egg cells of a closely related species. The modified embryo is then transplanted into a surrogate mother, which gives birth to an organism genetically identical to the extinct species.

Genome editing, particularly through Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR), alters the DNA of living species by introducing genes from extinct species. Back breeding involves breeding animals for an external characteristic that may not be seen throughout the species. This method can recreate the traits of the extinct species.

Species for Resurrection

Researchers are attempting to bring back several extinct creatures, and one has already been revived.

Dire wolf: In April 2025, George Church, founder of Colossal Biosciences, Laboratories, USA, announced the successful birth of three dire wolf pups, establishing the species as the first successfully de-extinct species — a historic milestone in conservation science. Researchers obtained genetic material from dire wolf fossils, including a 13,000-year-old tooth and a 72,000-year-old skull. From these remains, scientists sequenced and deciphered the dire wolf genome (complete set of DNA).

Using CRISPR genome editing, Church’s team edited living cells from the modern Grey Wolf (dire wolf’s closest living relative) to carry dire wolf genes. These edited cells were used to create embryos through Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer, replacing the genetic material in donor egg cells with the edited dire wolf DNA. The viable embryos were implanted into domestic dog surrogates, resulting in the birth of three healthy dire wolf pups: two males (Romulus and Remus) and one female (Khaleesi). These pups already exhibit classic dire wolf traits such as thick white fur, broad heads and sturdy builds, and display wild lupine instinct unlike domestic dogs. This initiative adhered to IUCN guidelines on creating proxies of extinct species for conservation purposes.

Church asserts that another major disruptive conservation project aims to introduce the woolly mammoth gene into the Asiatic elephant for conservation purposes. There is a possibility that species such as woolly mammoth, passenger pigeon, dodo, quagga and aurochs, supported by well-preserved DNA samples, may potentially return in modified forms.

De-extinction in India

The de-extinction efforts in India are primarily focused on the reintroduction of the Asiatic cheetah, declared extinct in 1952. While no major CRISPR-based projects are under way, the possibility is being explored, particularly through the Lazarus project, which collaborates with Indian researchers on reviving the extinct Himalayan quail using DNA from museum specimens.

Resurrected species would remain highly vulnerable and require long-term protection. Concerns also include whether they can adapt to today’s environmental conditions and reproduce successfully in the wild

De-extinction and Conservation

Conservationists view de-extinction as a form of ‘deep ecological enrichment’ aiming to restore ecosystem functions lost through extinction. Releasing resurrected animals into suitable habitats can increase biodiversity and improve ecosystem resilience.

For instance, woolly mammoths were dominant herbivores of the ‘mammoth steppe’ in the far north, once the largest biome. Their disappearance allowed species-poor tundra and boreal forest to replace productive grasslands. Their return could help revive carbon-fixing grasslands and reduce greenhouse gas-releasing tundra, thus combating climate change. Similarly, the European aurochs, extinct since 1627, helped maintain forests, mixed with biodiverse meadows and grasslands, across all of Europe and Asia.

De-extinction measures would initially be necessary to reintroduce a species into the ecosystem until the revived population can sustain itself in the wild.

Advantages of De-extinction

Developing de-extinction technologies may lead to large advances in the field of genetic technologies that improve the cloning process and prevent endangered species from going extinct; medical research as a cure to diseases could be discovered by studying revived previously extinct species; and conservation outreach with revived species acting as ‘flagship species’ to inspire public interest in conserving ecosystems.

De-extinction has already driven progress in developmental biology and genetics. Reconstructing extinct genes may also help restore genetic diversity in threatened species. However, there is also a danger that the reintroduced species may negatively impact the existing ecosystem if they behave as invasive species. Their new environment may not support their survival.

Ethical Ramifications

These powerful technologies carry significant ethical ramifications. De-extinction provides an opportunity to rectify past human-driven extinctions. But many extinct species vanished due to habitat loss. In addition, resurrected species would be considered endangered and require sustained protection. Concerns also include whether they can adapt to the current environmental conditions and produce viable offspring.

De-extinction is a powerful tool, but not a substitute for current conservation efforts. It may help repair damaged ecosystems by reintroducing species with crucial ecological roles, restore lost biodiversity and complement ongoing initiatives to protect the plant’s remaining species. A robust scientific evaluation of de-extinction is essential to ensure that this technology is used responsibly for the betterment of the planet’s ecosystems and, in turn, the world as a whole.

(The author is a retired Indian Forest Service officer)

Related News

-

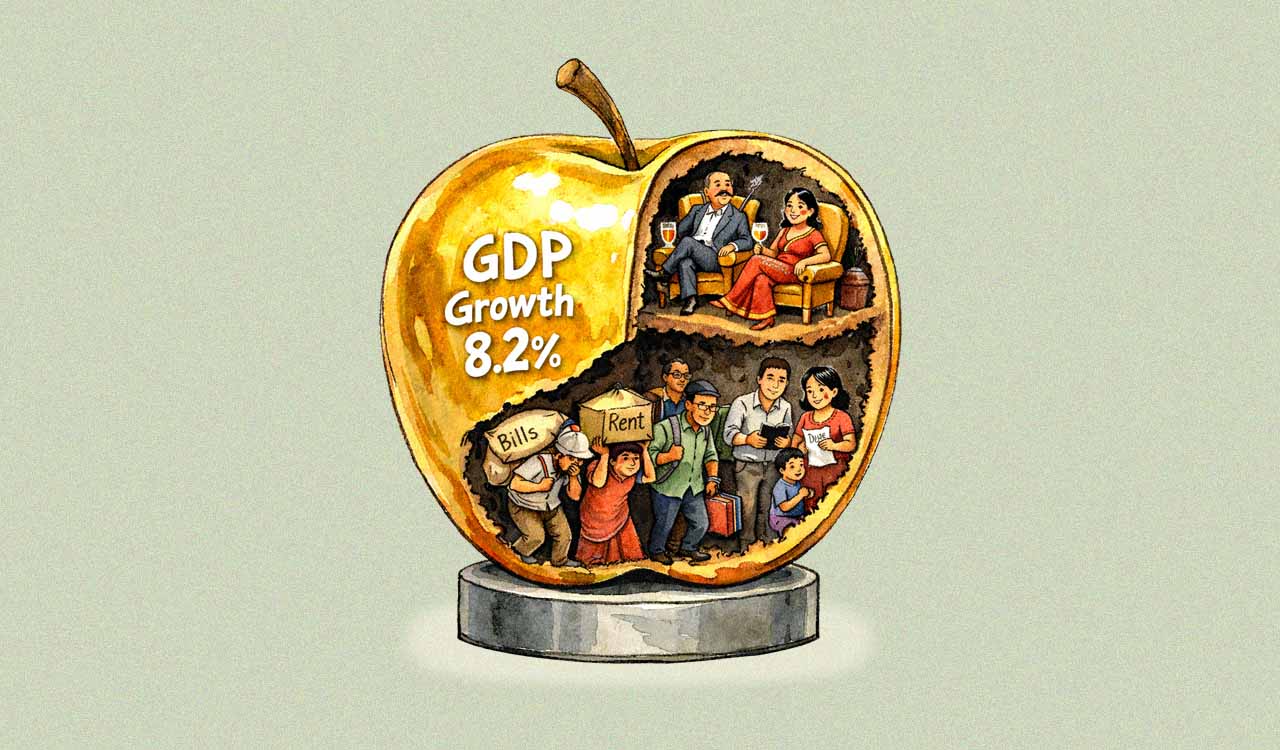

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Opinion: War of narratives, attrition — Reading Iran–US–Israel escalation through India’s lens

-

Telangana: Junior lecturers seek rescheduling of Inter vocational evaluation camp

2 mins ago -

Principal thrashes 15 polytechnic students with cable wire

7 mins ago -

Women’s Day celebrated with fervour in Telangana’s Mancherial

13 mins ago -

BRS MLC Sravan slams TDP for its rhetoric in Parliament against Telangana

19 mins ago -

Sarpanch, villagers protest for Mission Bhagiratha drinking water in Nagarkurnool

22 mins ago -

Congress preaches constitutional morality in Delhi but violates it in Telangana, says Harish Rao

25 mins ago -

Another Million March needed against Congress government, says Srinivas Goud

30 mins ago -

Police stop BRS leaders from serving food to Velugumatla displaced families in Khammam

30 mins ago