Opinion: Vande Mataram — reclaiming Bankim Chandra’s moral rights

The Home Ministry’s decision to restore all six stanzas of Vande Mataram on its 150th anniversary reaffirms the principle that literary works must be preserved in their authentic, unaltered form

By Dr GR Raghavender

The Union Home Ministry’s order dated February 6, 2026, directing the restoration of all six stanzas of the national song, Vande Mataram, marks a significant moment in India’s cultural and legal history, especially in the context of India’s freedom struggle. The decision coincides with the 150th anniversary of Bankim Chandra’s immortal composition. The removal of four stanzas and retaining only two stanzas was a historic blunder. The restoration of the complete song is necessary to honour India’s cultural roots. Beyond contemporary politics, the selective use of two stanzas raises a deeper issue: the violation of the author’s moral right and the right to integrity and respect for the work that embodied the author’s spiritual and civilisational vision of the motherland, Bharat.

Also Read

Vande Mataram, originally composed as a six-stanza hymn in Bankim Chandra’s 1882 novel Anandamath, serves as an ascending tribute to Bharat Mata. The poem begins with evocative imagery of India’s natural beauty, highlighting its rivers and greenery. It subsequently elevates the motherland to a sacred symbol of strength and wisdom, incorporating references to Hindu goddesses Durga, Lakshmi, and Saraswati. This progression reflects a journey from geographic admiration to divine reverence, encapsulating India’s 5,000-year-old cultural heritage and patriotic devotion.

Truncation

In 1937, the Indian National Congress, led by Jawaharlal Nehru and acting on suggestions from Rabindranath Tagore, decided to omit the last four stanzas of the song to avoid explicit references to a Hindu goddess, seeking to present a more so-called inclusive version. This truncation obscured the full vision of Bankim Chandra’s work. Such mutilation can be seen as a distortion of the work, rendering it imperfect. Later, this selective version of Vande Mataram was adopted as the national song on January 24, 1950. However, the truncated version of the song persisted for decades.

The structural unity of the six-stanza hymn emphasises its significance in representing India’s heritage, spiritual traditions, and civilisational ethos. Removing four stanzas diminishes the authentic voice of the author and weakens the portrayal of Bharat Mata and the Hindu cultural context. Bankim Chandra aimed to inspire patriotism through his work, utilising poetic symbolism from the Sanatan tradition, particularly the imagery of goddesses, to evoke national pride and unity during the colonial era. His intent was not sectarian but deeply rooted in cultural heritage, reflecting a call for integrity and cultural development, as seen in the Vande Mataram movement against British oppression.

Copyright Perspective

From a copyright perspective, this prolonged truncation raises serious concerns regarding the author’s moral right, which is inalienable. The Copyright Act of 1914, introduced during the British colonial era, protected only economic rights. Moral rights are rooted in the French concept of Droit Moral, which recognises the author’s personal connection with the work. International recognition came only after the 1928 revision of the Berne Convention. Thus, in 1937, the legal framework in India did not explicitly protect the author’s moral right, that is, the right to integrity. It is plausible that political leaders of the time were unaware of this doctrine when selectively mutilating the song.

The Copyright Act, 1957, enacted after India’s independence, introduced moral rights for authors through ‘authors’ special rights’, allowing them to claim damages for any detrimental alterations to their work. Amendments to the Act in 1994 and 2012 reinforced these moral rights alongside economic rights, ensuring that authors retain the right to integrity even after economic copyright expires, thereby protecting their creative identity.

In the landmark Amarnath Sehgal case, the Delhi High Court upheld an author’s right to integrity, declaring that moral rights are the very soul of a creative work. The judgment underscored the imperative to preserve and protect literary and artistic creations in their original form

Judicial recognition of moral rights can be seen in cases such as Manu Bhandari vs Kalavikas Pictures, where the Delhi High Court stated that a creative work reflects the creator’s personality. Distortion or mutilation can harm the author’s honour, as seen when only a part of Vande Mataram is presented, which effectively fragments its artistic unity and diminishes its cultural symbolism within India.

In Amarnath Sehgal’s case, the Delhi High Court upheld the right to integrity and declared that the moral rights of authors are the soul of their works, emphasising the necessity of preserving and protecting them. However, in the case of Bankim Chandra, the assertion of such rights after his death posed difficulties, as neither he nor his heirs could contest the alterations to his work. The 1937 selective alteration of a song dedicated to the motherland is considered by some a severe insult to both the author and the nation, akin to the partition of India in 1947, representing a betrayal aimed at appeasing certain communities.

Right to Integrity

Authorship is crucial in shaping a nation’s culture and understanding its development. The right to integrity is essential for protecting cultural heritage, which includes artists as valuable resources. Moral rights legally safeguard India’s cultural heritage through artists’ rights. Vande Mataram, as conceived by Bankim Chandra, expresses devotion to Bharat Mata and underscores the need to preserve a literary work true to its original intention and undistorted form.

The latest order by the Union Home Ministry restoring all six stanzas, therefore, represents more than a commemorative gesture. It symbolically restores the integrity of Bankim Chandra’s original creation and reaffirms the principle that literary works must be preserved in their authentic and unaltered form. Marking the 150th anniversary of its composition through the reinstatement of the complete text honours not only India’s rich cultural heritage but also upholds the enduring moral rights of its author.

(The author is an Intellectual Property law and technology expert, Senior Consultant in Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT), Ministry of Commerce and Industry, a retired Joint Secretary, Government of India, and former Registrar of Copyrights. Views are personal)

Related News

-

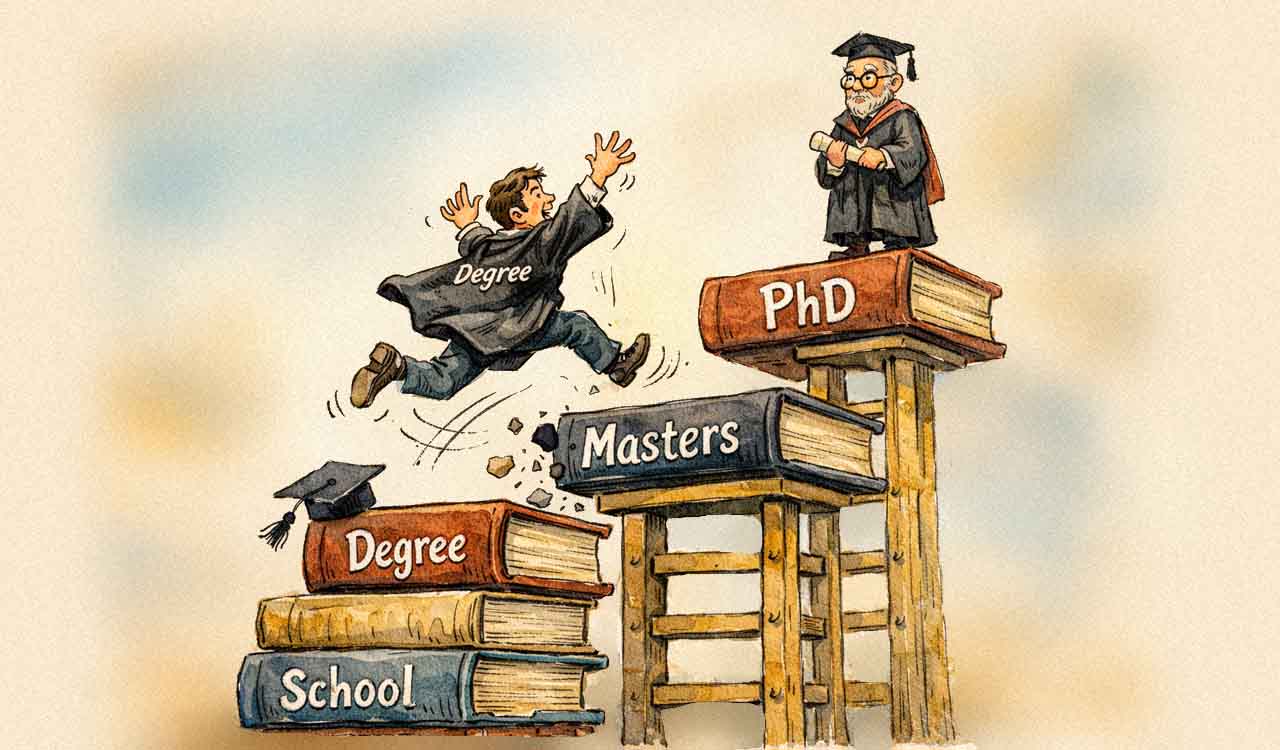

Opinion: Skipping a Master’s degree may weaken research quality

-

Opinion: Prashant Kishor — the kingmaker who could not crown himself

-

Opinion: From strategic depth to strategic discord: Why the Taliban-Pakistan rift is reshaping the region

-

Opinion: India’s paraquat paradox, a poison still within reach

-

Sam celebrates Holi on sets of ‘Maa Inti Bangaaram’

24 mins ago -

Telangana: Two drown in Godavari river after Holi celebrations in Manugur

40 mins ago -

Naga Chaitanya’s Vrushakarma: Sathya’s Balaji look unveiled on birthday

1 hour ago -

Two foreign nationals arrested with MDMA worth Rs 25 lakh in Hyderabad

1 hour ago -

Sri Lanka rescues 32 sailors from sinking Iranian naval ship

1 hour ago -

Study warns of extinction risk for lion-tailed macaques

2 hours ago -

IIT Hyderabad to host national symposium on accessible, inclusive digital library

3 hours ago -

Blood Tests to Consider When Facing Sudden Hair Fall

3 hours ago