Opinion: Why Constitution (130th) Amendment Bill will be difficult to implement

Despite aiming to ensure probity among top leaders, the Bill is legally and practically flawed— from violating SC rulings to governance paralysis

By E Damodar

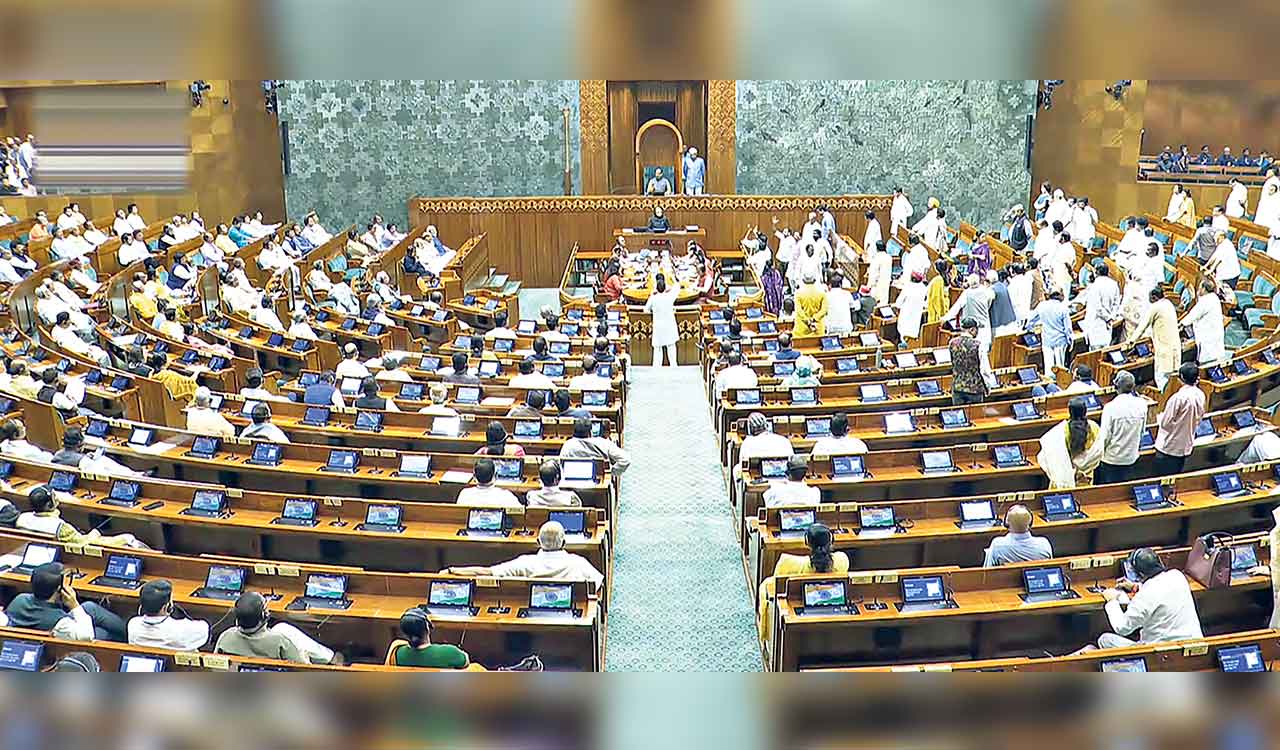

The Constitution (130th) Amendment Bill, 2025, along with the allied Bills, was tabled in Parliament on 20th Aug 2025 and referred to the Joint Parliamentary Committee for scrutiny. Though the Bills appear to be morally sound — to ensure integrity among high echelons of the government — they bristle with inconsistencies. The Bills suffer from legal infirmity, poor drafting, and, in practice, may be difficult to implement.

Also Read

The gist of the three Bills is that if the Prime Minister, a Chief Minister, or a Minister is arrested and detained for 30 days for an offence carrying a punishment of 5 years, s/he shall cease to hold the office on the 31st day.

The Bills read ‘if arrested and detained in an offence punishable with five years or more of imprisonment’. However, this is against the settled law laid down by the Supreme Court. In Arnesh Kumar V State of Bihar (July 2014), the SC ruled that in cases where the alleged offence is punishable with imprisonment of up to seven years, the police cannot automatically arrest the accused. For the last one decade, this principle has been consistently applied as binding law. Contrary to this, the present Bills stipulate offences punishable with 5 years or more of imprisonment. This basic flaw in the drafting of the Bills renders implementation infructuous.

Flowing from the ruling in the Arnesh Kumar case, Section 41A is inserted in CrPC (Section 35 of BNSS – the new avatar of CrPC). This Section lays down the procedure of issuing a notice without resorting to arrest. As the latter part of the Section permits arrest in special conditions, the respondent has the option to move court for anticipatory bail. We have seen that on innumerable instances, the judiciary has sanctioned bail in such cases. Thus, legally, the likelihood of arrest, envisaged in these Bills for offences punishable with five years of imprisonment, is nugatory.

The Bills Are Unconstitutional

The principle of equality under Article 14 of the Constitution guarantees equality before the law. The Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988, and other statutes define Ministers, including the Prime Minister and Chief Ministers, as Public Servants. If a Public Servant is remanded for 48 hours, they are automatically suspended and remain in suspension for six months, with a review after six months.

Then why does the proposed Bill provide a special 30-day detention rule for ‘Public Servants’ in higher positions of government?

The Bills Are Generous

On the 31st day, if emancipated, these elite public servants will resume office automatically. These ‘concessions’ are contradictions in a democratic polity and will not stand judicial scrutiny.

On the matrix of practice also, the Bills appear untenable. Suppose a Chief Minister under detention for 30 days ceases to hold office on the 31st day. Who will then be the Chief Minister till the Legislative Party elects a new leader, which may take a week or so? Who will govern the State during the interregnum? Will the President’s Rule be promulgated? Further, if the outgoing incumbent, who lost office on the 31st day, is released from detention after a new Chief Minister is sworn in, what will be his status? Will he just be a member of the Legislative Assembly?

The Bills, if implemented, will have serious repercussions for governance. For instance, if a Chief Minister or Minister in charge of Internal Security is detained, and communal disturbances, law and order crises or natural calamities arise, who will manage the situation? Governance cannot be left in the lurch.

In Arnesh Kumar V State of Bihar (July 2014), the Supreme Court ruled that for offences punishable with up to seven years in jail, the police cannot automatically arrest the accused — a principle followed as binding law for the past decade

With regard to the offences punishable with imprisonment up to 5 years, this appears to be based on a recommendation made by the Law Commission in February 2014 — a good five months before the ruling of the Supreme Court in the Arnesh Kumar case. Between a recommendation of the Law Commission (an advisory body) and the ruling of the Supreme Court, the latter prevails. The Drafting Team in the home ministry is perhaps oblivious of the ruling of the apex court. (Article 141 states that the law declared by the Supreme Court shall be binding on all courts within the territory of India).

Law Panel Report

The Law Commission of India (Chairperson, Justice AP Shah) submitted its report on electoral disqualifications to the Ministry of Law and Justice on February 24, 2014. The report follows the Supreme Court directive issued in December 2013, in the public interest litigation filed by the NGO Public Interest Foundation related to the decriminalisation of politics. The report examined issues related to the disqualification of candidates with criminal backgrounds and the consequences of filing false affidavits.

Even the Law Commission did not suggest ceasing to be in the office upon arrest and detention for 30 days. The Commission suggested disqualification on ‘Framing of charges by the trial courts’. Framing of charges ensues after the police file the charge sheet, and is deemed to be ‘judicial cognisance’.

If the intention is to enforce morality and probity among the elected representatives, then a separate law has to be enacted to provide for joint investigation agency, consisting of State police, CBI and Director of Lok Pal/Lok Ayukta, and constitution of separate courts with a strict deadline of completing investigation in 2-3 months and non-stop trial within the same timeline.

How can a high-ranking functionary of the government, such as a Chief Minister or Minister, operate within the confines of a prison for 30 days? During the incarceration of Arvind Kejriwal, the country saw how governance in Delhi was paralysed.

In view of the frequent deployment of agencies like the CBI and ED against elected representatives in opposition-ruled States, these Bills raise suspicion. While the stated objectives of the Bills may appear lofty, they suffer from flaws on both legal and practical fronts.

(The author is a retired IPS officer and served as IG of Police)

Related News

-

Congress leader moves SEC against party MLA over poll malpractice

10 hours ago -

BRS seeks action against Jagga Reddy, flags counting day threat

10 hours ago -

High voter turnout recorded across 19 municipalities in erstwhile Medak district

10 hours ago -

Salman’s brother-in-law gets threat email; Bishnoi gang link suspected

10 hours ago -

BRS slams police inaction over alleged attack by Jagga Reddy

10 hours ago -

Candidate distributes fake gold coins to lure voters in Sircilla

10 hours ago -

Jagga Reddy blames SEC for Sangareddy polling incident

10 hours ago -

India prepare for Pakistan showdown after Namibia game

11 hours ago