Opinion: Mumbai’s hidden backbone

The government must consider the informal slum settlers as citizens with rights and goals rather than as invaders

By Saikat Sarkar, Shayan Das, Shatabdi Ghosh

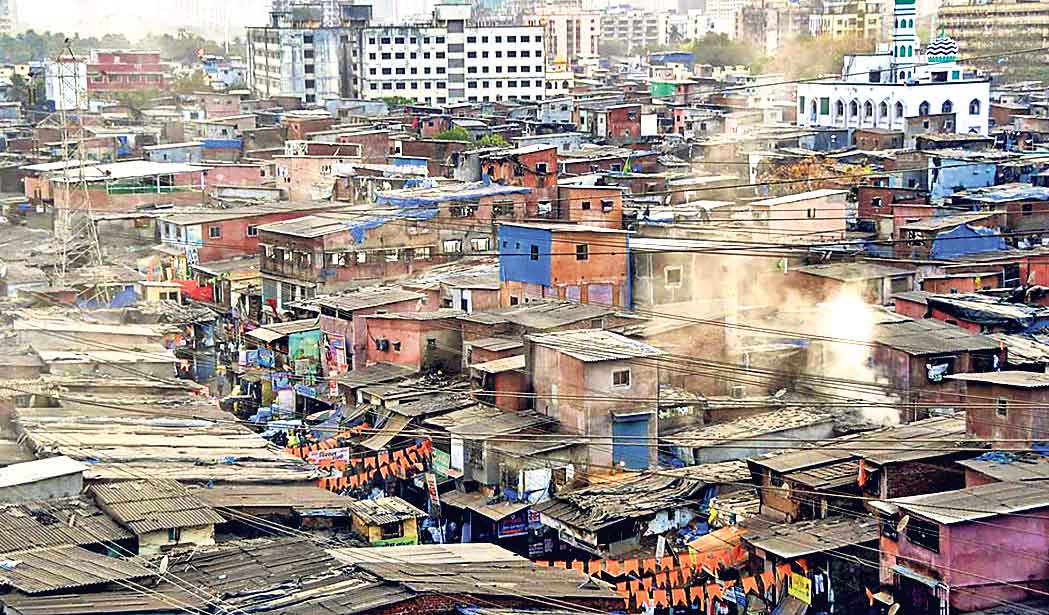

The city of dreams, the land of extremes, and India’s commercial centre, Mumbai, is both tragic and inspirational. Shining skyscrapers by the Arabian Sea on one side and millions squashed into thick informal settlements, the city’s hidden backbone, on the other. Each cup of tea from a roadside tapri, each building hosed down in preparation for dawn break, each construction site where activity is frenetic bears the sweat of such citizens on it.

Also Read

In Mumbai, more than 40% of people reside in slums, which are places that are not subject to official development regulations. They represent the everyday lives of millions of people who support the city’s economy yet are unable to take advantage of it. In addition to being overcrowded, slums lack official amenities, including safe housing, good sanitation, and clean water.

It is not poverty or homelessness; it is in the history and economy of the city. Since the middle of the 20th century, Mumbai’s industrial expansion has attracted migrants from all across India. The organised housing market, faced with pressure from high land prices and supply shortages, never succeeded in bringing this downpour into a settlement. Squatter settlements were a rational reaction to the collapse of the city’s planning.

These communities underpin the informal sector, which employs about 60% of Mumbai’s workforce. By providing homes for domestic workers, street vendors, and small-scale industry, informal settlements aid in the growth of the city.

Perpetual Struggle

Slum existence is a life of perpetual struggle. There is no adequate drainage, sewage disposal, or running water in any of the slums. Due to inadequate sanitation, outbreaks of waterborne illnesses like cholera and typhoid during monsoon rains result in public health problems. Slums are vulnerable to flooding and water contamination because of poor drainage.

The shantytowns of Mumbai are characterised as ubiquitous and hubs of resilience, inventiveness, and social cohesiveness

Past government policies have oscillated between neglect and coercion. Initiatives such as the Slum Rehabilitation Authority (SRA) seek to regularise and upgrade the living environment, but displace its inhabitants instead of empowering them. Developers gain, while the poor become more marginalised. Top-down without actual participation will have an equal tendency to perpetuate inequality rather than eradicate it.

Major Obstacles

Healthcare access is still a significant obstacle. People are forced to seek private treatment, which raises their out-of-pocket costs, because long wait periods at public health facilities cause them to lose their daily income. These issues, particularly when coupled with poor income, erratic work, and linguistic or cultural obstacles, greatly impair their capacity to maintain good health. Inadequate maternal care can increase a woman’s risk of sexual and reproductive health problems and lead to unfavourable birth outcomes.

Additionally, there is a great deal of mental and psychological suffering, with greater rates of anxiety and despair, when compared to the non-migrant group. Social isolation, difficulties assimilating, unemployment, and irregular income are a few of the elements that lead to poor mental health.

Mobilisation Matters

Mobilisation is a way to actual change. Mobilisation is not just protest; it’s participation, organisation, and control. The power dynamic starts to shift when people come together to express their needs, bargain for authority, and assert their rights. The Society for the Promotion of Area Resource Centers (SPARC), Mahila Milan, and the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) in Mumbai served as examples of how social action may raise living standards. They made it possible for community organisations to organise savings clubs, conduct housing surveys, and engage in direct negotiations with the Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai (MCGM) for improved land tenure security and sanitation.

Additionally, social capital—the networks and trust that strengthen communities—is created through mobilisation. People can bargain with authorities, obtain goods and services, and resist evictions through self-help groups, neighbourhood associations, and federations. Collective power turns into a resource that may be utilised to improve livelihoods and assert rights.

Local Governance

For sustainable mobilisation, the governance must be attuned. The government must consider the informal settlers as citizens with rights and goals rather than as invaders. Participatory platforms such as ward committees, social audits, and community mapping can aid in bridging the gap between the people and the government. Change can be leveraged through research, civil society collaborations, and private entrepreneurship.

NGOs can enable organisational action, research institutions can enable advocacy by evidence, and companies can invest in socially inclusive city development. Programmes such as the Slum Sanitation Programme demonstrate how people planning engagement leads to improved outcomes.

The Municipal Climate Action Plan’s (MCAP) resilience is the subject of the other significant conversation. The poor are disproportionately affected by heat, air pollution, and floods. Bringing them in is not a matter of social need but a matter of environmental need, too. They must be brought into the city’s climate action, or else its plans will collapse.

Inclusive Urban Future

Demolitions and short-term rehab schemes won’t fix informal settlements’ ills. A shift in perspective is required, with them no longer being seen as “illegal” but rather as an integral aspect of the city’s social and economic life. Housing is not a privilege but a right.

The answer to this transformation is mobilisation. Responsibility, ownership, and sustainable development are given birth to through participation. Decision-making through consensus is more effective than decisions that are imposed. Above all, mobilisation converts the urban poor into givers, not takers.

The shantytowns of Mumbai are characterised as ubiquitous and hubs of resilience, inventiveness, and social cohesiveness. The challenge is not to remove them from the city but to integrate them through inclusive policy, democratic administration, and sustained mobilisation.

The dignity that the city’s builders are guaranteed is a better indicator of Mumbai’s development than the quantity of opulent skyscrapers it builds.

Through mobilisation, these communities are able to assert their legitimate position as citizens influencing the future of the city they support, rather than as outsiders. In the words of Noam Chomsky, “Unless people can see illusions, they can’t move to correct them.”

(The authors are independent researchers)

Related News

-

Harish Rao to visit illegal quarry in Neopolis on Thursday

1 min ago -

Holi celebrated with enthusiasm in Kothagudem, Warangal

8 mins ago -

BRS leaders come to the rescue of Velugumatla displaced families

19 mins ago -

Allen crushes South Africa dreams with record century, Kiwis storm into T20 World Cup final

27 mins ago -

Congress councillor disqualified in Isnapur Municipality for voting against party whip

29 mins ago -

KTR condemns civilian deaths following Israel-US bombing in Iran

36 mins ago -

Podu farmers clash with forest staff in Telangana’s Aswaraopet

44 mins ago -

20-year-old bride dies by suicide 8 days after marriage in Medak

55 mins ago