Stalemate in Godavari-Cauvery river link: States clash over water share amid BJP’s push for consensus

The Godavari–Cauvery river interlinking project is facing stiff resistance from riparian states, particularly Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha, over concerns of water diversion from Chhattisgarh’s allocation. Meanwhile, Telangana has softened its stance by agreeing to Inchampalli as the diversion point.

Hyderabad: The Godavari-Cauvery river interlinking project faces mounting hurdles as riparian States voice sharp opposition to diverting water from Chhattisgarh’s unutilized share. Despite the BJP-led Centre’s support, key States like Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh and Odisha are resisting, highlighting the project’s reliance on 147 TMC of water allocated to Chhattisgarh.

While the administrations in the BJP and TDP ruled States are maintaining resistance, prioritizing riparian rights over national projects, much in contrast, the Congress-ruled Telangana has made a compromise, agreeing to Inchampalli as the source despite impacts on downstream projects like Medigadda. Under the previous BRS regime, Telangana opposed diversions while its lands remained parched, but the current government seeks a compromise.

Also Read

Officials proposed raising Inchampalli’s height for 200 TMC of floodwater utilization and two new Krishna basin reservoirs stating that the State would be cooperating for national interest as its 968 TMC Godavari entitlement must be protected. The Central Water Commission (CWC) has clarified that the diversion of Chhattisgarh water would be temporary, as long-term plans are in consideration to augment supply from Himalayan rivers.

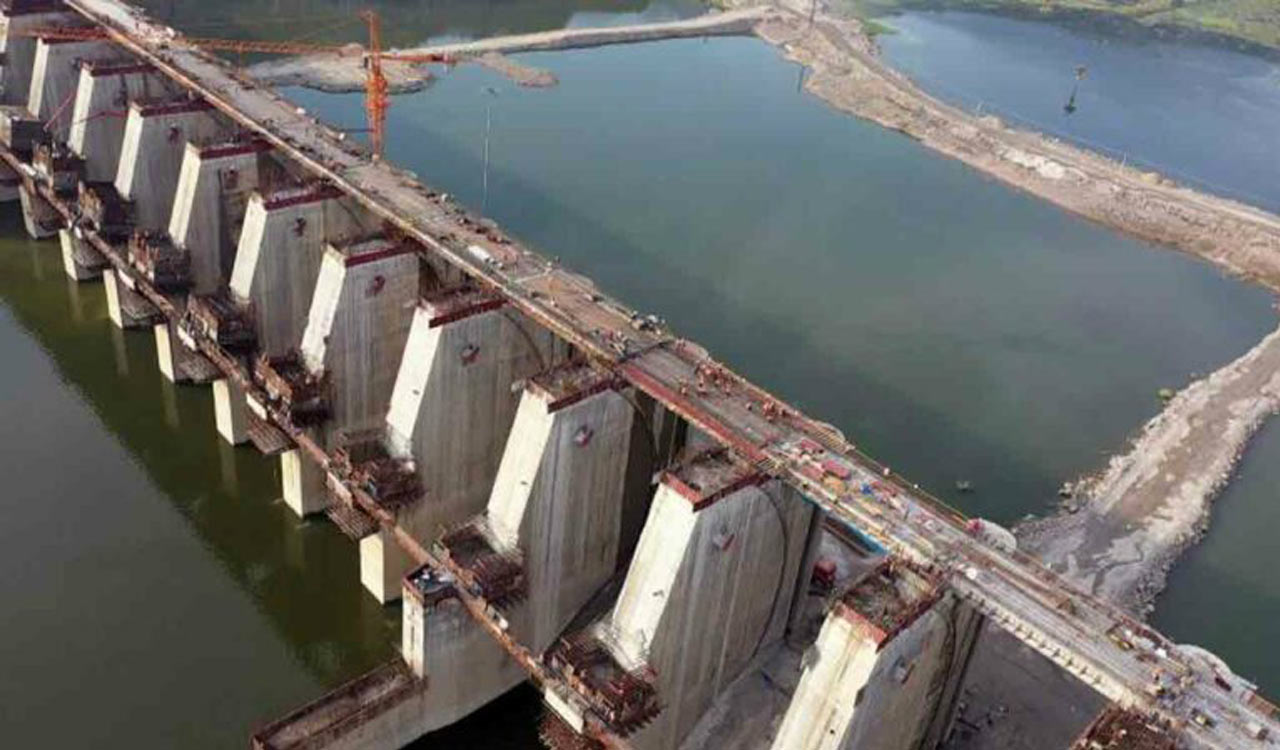

The project aims to transfer surplus Godavari water via a network of canals and reservoirs, starting from Inchampalli barrage in Telangana, through Krishna’s Nagarjuna Sagar, Pennar’s Somasila, and into Cauvery’s Grand Anicut, to irrigate drought-prone areas in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Puducherry.

Envisaged to benefit 9.44 lakh hectares of farmland and provide drinking water to villages en route , it promises to address chronic water scarcity in southern basins.

No true surplus with Chhattisgarh

However, the NWDA’s detailed project report (DPR), circulated in 2021 and updated recently, has sparked inter-state friction. Of the proposed 148 TMC diversion, allocations include 44 TMC each for Telangana and AP, 16 TMC for Karnataka, and 41 TMC for Tamil Nadu. Yet, upstream States argue there is no true surplus, with Chhattisgarh’s current utilization at just 20-30% but plans to ramp up to 70-80% through new projects like Bodhghat.

Chhattisgarh, under BJP rule, has reiterated its opposition in state assembly debates (2021-2022) and communications to the Ministry of Jal Shakti. A 2021 Water Resources Department report warns that post-project, the state’s “surplus” could drop to near zero during non-monsoon months.

Officials contend that diverting their 147 TMC share infringes on riparian rights, especially as topography limits full utilization but future dams will close the gap.

“We have no surplus left after our needs,” a senior Chhattisgarh irrigation official told NWDA during the sixth consultative meeting in Hyderabad on August 23. This stance echoes broader concerns, with the state halting new barrage proposals pending tribunal outcomes.

Even NDA ally Andhra Pradesh has opposed Inchampalli as the diversion point in the latest NWDA meeting. AP prefers Polavaram as the source, arguing that Inchampalli floods coincide with Krishna inflows, complicating operations.

“Diverting Chhattisgarh’s share via Inchampalli would erode our downstream rights,” AP representatives stated, challenging CWC’s hydrology report as “unrealistic.”

Odisha, also BJP-governed since 2024, remains largely unsupportive, boycotting NWDA meetings in 2023-2024 and pushing for basin-wise management. The State views Godavari-Cauvery links as one interlinked with its Mahanadi disputes with Chhattisgarh, where upstream diversions threaten 60% of Odisha’s irrigated agriculture impacting livelihoods for over 10 million people.

Related News

-

Harish Rao calls out Revanth Reddy govt for sabotaging Telangana’s water rights

-

Uttam Kumar promises completion of Krishna basin projects in three years

-

Harish Rao slams Congress govt’s delayed Supreme Court move on Andhra’s Polavaram-Nallamala Sagar link project

-

Telangana reaffirms stand on Godavari–Cauvery link, rejects Andhra’s Polavaram route

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

7 hours ago -

SJFI national convention returns to Delhi with Hero MotoCorp as title sponsor

7 hours ago -

Delhi beats Hyderabad by nine wickets in BCCI women’s under-23 one-day championship

7 hours ago -

Hyderabad player Sowmith Reddy wins Unrated Chess Tournament at A2H Chess Academy

7 hours ago -

Editorial: T20 World Cup glory— rise of the Blue Tide

7 hours ago -

HC clears Ram Rahim in murder case, says CBI acted under pressure

7 hours ago -

Nampally court dismisses Sakala Janula Samme case against KCR, KTR

8 hours ago -

Bhoodan land row: 43 booked for violent protests in Khammam

9 hours ago