A Midnight Dreary

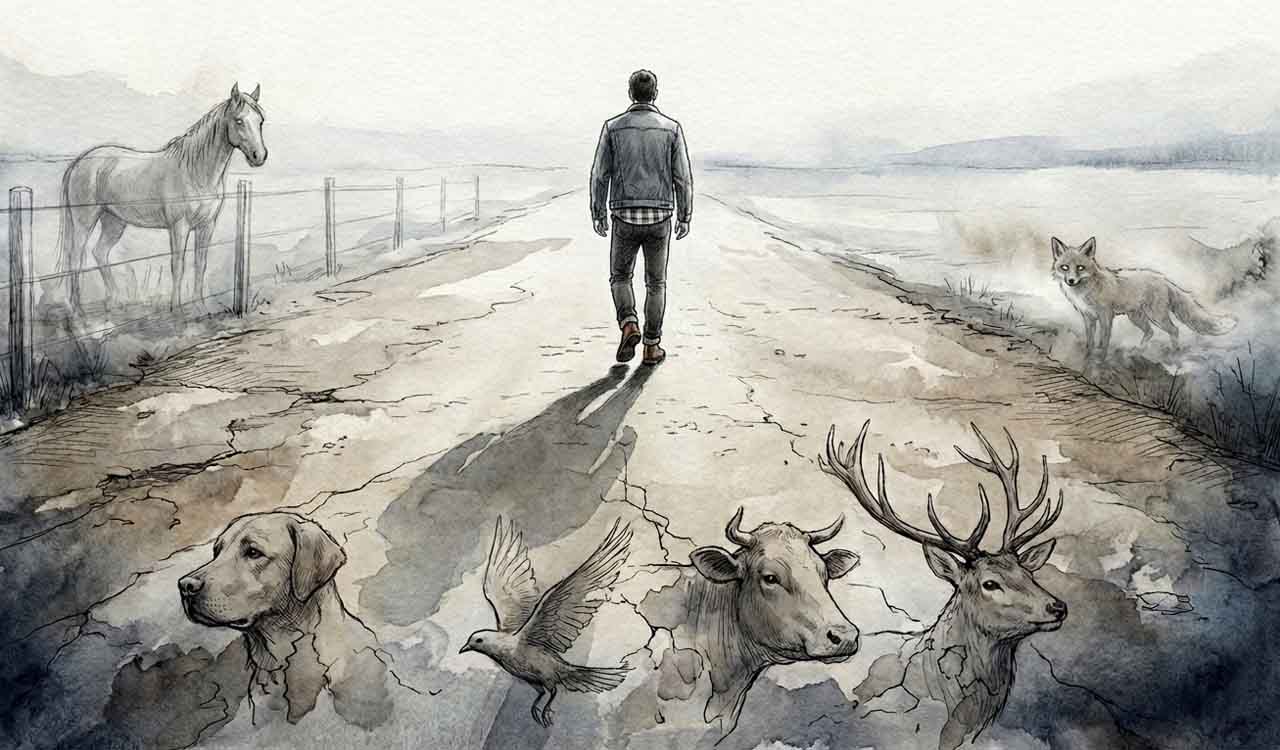

As we grieve, experience loss and get mired in melancholy over the recent incidents, like Poe’s Raven, there is only one response: Nevermore

By Pramod K Nayar

A bird, often treated as a reminder of despair and a symbol of mourning, arrives at the home of a man already distressed and depressed from the loss of his beloved. He solicits, in his delirious, melancholic but also intellectually inquisitive – he is a student – state, the reason for the bird’s visit and information about his dead beloved. But to all his queries, the bird, black, brooding, beautiful, has only one response: “Nevermore”.

The short narrative poem that tells us the story of unending grief and the interminable nature of experiencing loss, celebrates its 175th anniversary this year: Edgar Allan Poe’s deservingly famous “The Raven”, was first published in 1845.

Poe (1809-1849), often credited with the creation of the first closed-room mystery (“The Murders in the Rue Morgue”), was a journalist, poet, essayist and short story writer. Several Poe tales have been anthologised endlessly: “The Fall of the House of Usher”, “The Masque of Red Death”, “Premature Burial”, “The Tell-Tale Heart”, “The Black Cat”, “The Gold Bug”. Others like “The Purloined Letter” have provided critics and philosophers (Marie Bonaparte, Jacques Lacan, Jacques Derrida) limitless delight for their theories.

The journal devoted to Poe – The Edgar Allan Poe Review – provides a forum for many scholarly interpretations of his work. Physicians and biomedical researchers, in essays published in The Lancet and American Journal of Cardiology, have detected various conditions such as Capgras syndrome, Marfan syndrome and frontal lobe degeneration, once again demonstrating his appeal to an unexpectedly diverse audience. His characters are uniformly tormented souls. Merging Gothic terror with horror, and thereby both fear and revulsion, Poe’s grotesque tales often subsume the potential and possibilities of his poems (“Annabel Lee”, “Alone”, “Lenore”, “The Bells”).

“The Raven” is his classic work. The 2012 John Cusack film (which brings together many of the Poe tales), Duncan Long’s graphic novel (2015), Gustav Doré’s amazing illustrations for the 1883 edition, James Carling’s illustrations, all have added to the power of “The Raven”, and its popularity. Incidentally, a talking raven is not original to Poe: Charles Dickens had just such a creature, named Grip, in Barnaby Rudge, and Poe had loved Dickens’ novel (the critic Matthew Redmond makes the connection in a recent essay).

The Avian Uncanny

Birds in poetry are at once earthy and transcendent, soaring above the quotidian (recall the English Romantic poets’ obsession with skylarks and nightingales). Poe’s Raven is a common enough bird which, by speaking, immediately sets itself apart from its feathered cousins. Poe’s Raven has been denaturalised when he makes it, like in fables, to speak. However, as critics Timothy Farrant and Alexandra Urakova note and the speaker records in the course of the poem, the bird only enunciates, mechanically, one word, being almost parrot-like in its repetition. Poe, therefore, simultaneously bestows a uniqueness to the bird and limits its so-called singularity.

The bird is at once familiar and not, evoking what Freud would famously theorise as the uncanny. The atmosphere, which is central to the uncanny, is of course typical of Poe. “The Raven” opens with the speaker describing his state: it is a “midnight dreary” (incidentally, now a catch phrase), in “bleak December”. He was trying, unsuccessfully, to forget his now dead Lenore:

each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore

Mired in melancholy, he hears a tap-tap at his door, which, he says, “filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before”. He pretends it is just a traveller. Poe, as is demanded of the uncanny, which relies on uncertainty and the ambiguities of meaning, plants a doubt in us: does the speaker really hear a tap-tap, or is it wishful thinking that the “sounds” (like the muddy footprints inside the house in Stephen King’s Pet Sematary) indicate the return of his dead darling? Ever hopeful that the dead would return (Poe was always worried about premature burial, and his stories are full of such examples), he opens the door and asks: “Lenore?” The house he knows well is suddenly a place of terror, a home is now a place of mourning and despair rather than comfort and security. He no longer feels “at home” – the precondition of the uncanny (unheimlich, the German word for the uncanny, means “unhomely’) – in there.

Note the various names, ranks and social links the speaker attributes to the bird. He first characterises it as a “visitor”, attributes a certain aristocratic bearing (“lordly name”) and even thinks of the Raven as a “friend” who would also, unfortunately, abandon him. He then sees it as a bird once owned by a “master”, thereby attributing a pet’s or slave-object’s status to the Raven. At the end of the poem, he refers to it as a “demon”. The poem’s sliding scale of naming and therefore attributes, is important for the avian uncanny: the speaker ranges and rages across familiarity (friend), outsider (visitor), lordly, slave (object) and demon (other-worldly). The Raven shifts in meaning within the speaker’s perspective.

The bird brings the speaker’s memories to a crisis when he first expects the knock to mark the return of Lenore and second when he queries the Raven about his future reunion with Lenore. The uncanny, writes Amelia deFalco, the literary critic, is a “cohabitation of tenses”

The uncanny can be understood as the cohabitation of tenses, memories of a familiar past rubbing up against the strange newness of the present… I experience the uncanny when my expectations, inevitably based on memory, are upset; when the familiar, the recognizable, is infiltrated by the strange, the unrecognizable, that is, when the past and present fail to align properly.

For Poe’s speaker, the knocking and the Raven together induce a certain expectation: Lenore’s return. The house, which he perhaps inhabited with Lenore, is a familiar haunt, which generates memories of Lenore. The bird arrives as a stranger that refreshes memories and produces expectations of a return to the past. When the Raven says “nevermore” – indicating a future tense – to his inquiries regarding Lenore, the speaker’s despairing uncanny intensifies: he knows that his hopes for the future, which were based on his shared past with Lenore, are unfulfillable. The avian uncanny is the effect of this misalignment of his past with his fantasised future.

Despair … the Thing with Feathers

“Hope”, said Emily Dickinson, “is the thing with feathers”, thereby feathering another symbolic value. Poe has a different valence for the bird. When he opens the window and the bird comes in, to settle on the bust of Pallas – the goddess of wisdom – the speaker begins his interrogation. And the Raven has of course only one response: “Nevermore”. The speaker believes

Nothing farther then he uttered—not a feather then he fluttered—

Till I scarcely more than muttered “Other friends have flown before—

On the morrow he will leave me, as my Hopes have flown before.”

Then the bird said “Nevermore.”

The speaker speculates on the Raven’s provenance (and limited vocabulary). Its presence is at once stunning and awe-inspiring: “the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core”. The speaker decides the bird is a prophet who holds some secret of death and the afterlife, whether he would be reunited with Lenore:

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore

To this of course the wise Raven responds categorically, “Nevermore”, leading to a frenzied outburst from the speaker which, concluding the poem, also indicates his final descent into insanity:

“Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I shrieked, upstarting—

“Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!—quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”

And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

The bird, he believes, is still sitting on the bust, haunting the house, exactly like the unfinished business of mourning Lenore.

Here the bird as a symbol of “Nature”, arrives at a man-made construction – the house – to bring the news about death’s finality. The bird is also an instrument through which the addled mind of the speaker recognises a solemn truth: there is no return from the land of the dead. It is an instance of what Salvador Dali would term “concrete irrationality”. The Raven’s is the rational, measured voice that breaks through the fog of his despair and mourning and tells him the ineluctable truth about death – thus the Raven is perhaps a manifestation of his own conscience/voice/mind.

The bird is an object that comes to stand in for the thing that the speaker has lost. He chooses to fill his absence – Lenore – with the presence of a creature that he at once seeks aid from and fears. In continuation of the uncanniness of the apparition, Poe’s speaker “sees” the Raven as an interlocutor – since it “speaks” – and as a stranger.

The irony should not be lost sight of here. The speaker is a scholar, as symbolised in the books and the bust of Pallas. The poem demonstrates how this obviously educated man loses his rationality, starting to see the bird as possessing a royal mien, and refusing obeisance. He even begins to ask questions of the bird and think about a reunion with his dead lover. Moving beyond the madness theme, critics like Stephen Mirachi argue that Poe is invoking Christian thought here, by drawing on images of the Advent and the pulpit (the purple curtains in the poem echoing the purple cloth of the pulpit). Questions of life and death, of memory and forgetting, of presence and absence, are all invoked through the queries to the bird.

Haunting of Poe House

Poe’s speaker is dementing, as we can see. The house is now shared with the Raven, who seems to occupy the pride of place, on the Pallas bust. Thus, alongside his memories of – and possession by? – Lenore, the speaker is also haunted by the Raven. The emphasis in the last stanza, “still is sitting, still is sitting” is also a freezing of time: the bird is still, unnaturally so. Instead of doing what birds routinely do – “flitting” – this one just sits and stares malevolently, not unlike the cat or the eye that stares at and haunts the protagonists in other Poe tales (“The Black Cat”, “The Tell-Tale Heart”).

The haunted house is the house of despair, and Poe literalises the semantics of the term “haunt”: a haunt is a place where animals feed. Here the animal feeds off the speaker’s despair and deep melancholia. All of Poe’s houses, and stories, are haunts.

“The Raven” is still sitting there, in the house of Poe, remaining an irreducible and haunting presence in his oeuvre, the Gothic tradition and American literature. On the bird’s 175th birthday, Poe, long dead but speaking in a voice always cracked and coated by the crypt’s earth, signals to us the haunting is never complete. Poe’s Lenore, or Madeline Usher, are revenants, who begin life by coming back. The Raven has arrived and is here to stay, evermore.

(The author is Professor, Department of English, University of Hyderabad)

Now you can get handpicked stories from Telangana Today on Telegram everyday. Click the link to subscribe.

Click to follow Telangana Today Facebook page and Twitter .

Related News

-

Editorial: Delays hampering key science project

55 mins ago -

Opinion: Beyond misclassification: Recognising dignity, opportunity for DNTs

1 hour ago -

Union Minister Raksha Khadse stresses role of sports journalism

1 hour ago -

India topple Italy 1-0 to enter FIH Hockey World Cup Qualifier final

1 hour ago -

HCA funds: Telangana Cricket Association alleges fraud

1 hour ago -

Soukouna’s late goal gives Rajasthan United their first win of IFL 2025-26

2 hours ago -

Indian boxers assured of five medals in World Boxing Futures Cup

2 hours ago -

Two Indians killed in attack in Oman’s Sohar amid West Asia tensions

2 hours ago