Opinion: An unfair, unjustified cut

At a time when farmers needed more attention, Sitharaman has slashed the farm sector’s budget

By Kedar Vishnu, Ashish Andhale

We had huge expectations for the agricultural sector from the union Budget (UB) 2023-24. Many economists have praised the Budget mainly for two reasons. First, for increasing capital expenditure from Rs 7.50 lakh crore (Budget 2022-23) to Rs 10.01 lakh crore in UB 2023-24. Second, for increasing capital expenditure share in the total Budget from 19.02% to 22.23% in the same period. It is one of the best moves by the present government to promote manufacturing and bring global investors to India from the last three Budgets. The move shows that the government is emphasising Keynesian Theory for boosting economic activities in India.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has given much more importance to bringing stability to the economy. Fiscal deficit is estimated to be 5.6% of the GDP in UB 2023-24 compared with 6.4% in 2022-23. But has the Finance Minister tried to bring similar stability to the agricultural sector too? How is this Budget going to help the agricultural sector?

Drastic Slash

After withdrawing the three farm laws in 2021, we expected the Finance Minister would try her best to bring a significant reform while increasing capital expenditure on the agricultural sector. However, the allocation for the sector has been slashed drastically from Rs 1.33 lakh crore (2022-23) to Rs 1.25 lakh crore in 2023-24. The agricultural sector accounted for only 3.78% share of the total Budget share in 2021-22; it went down to 3.36% in 2022-23, and then again drastically down to 2.78% in the present Budget. (Budget at a Glance 2023-2024).

The average annual growth rate of agriculture declined to 3% in 2021-22 from 5.5% in 2019-20. Also, public expenditure in the sector has come down to 4% (Economic Survey, 2023-24).

Many have praised the Budget mainly for increasing overall expenditure by 14.1% as against the previous Budget. However, the share of the sector has reduced by 4.8% in the present Budget compared with 2022-23. The share of capital expenditure is just at 0.04%, and the remaining almost 99% of expenditure allocation is for the revenue account.

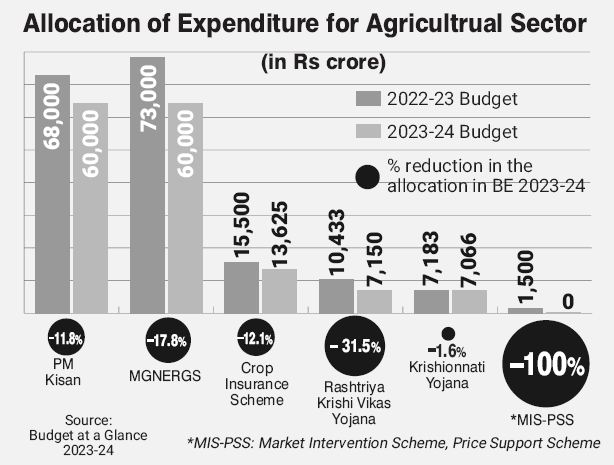

The government has reduced the allocation of major agricultural schemes even as farmers are facing problems of rising inputs costs and are not getting the remunerated prices for their products. (see infographics). Among all the schemes, MGNERGS has seen the most significant decline by Rs 13,000 crore (17.8% reduction in the UB 2023-24 as compared with 2022-23), followed by PM-Kisan grant by Rs 8,000 crore (17.8% reduction). This decline in funding will significantly reduce farmers’ income and adversely impact agricultural productivity. Moreover, rural labourers are going to have a very difficult time getting employment guarantees due to the slashing of funds for MGNREGA.

Significant Challenges

Farmers will face two significant challenges owing to the reduction of funds for following two important schemes. First, increase in production-related risk (natural calamities, pests, disease, etc) mainly due to a reduction in the fund for crop insurance schemes by 12.1% in this Budget. Second, increasing marketing risk due to the massive reduction in the fund from Rs 15,000 crore to Rs 10,000 lakh for the market intervention scheme and price support. Farmers would be more exposed to production-related risk and price fluctuation risk in upcoming years, putting them under more stress.

Market-driven Reforms

Without developing the agricultural sector and infrastructure, the government wants to introduce more market-driven reforms and shift from the production-driven sector. This shows that the government is slowly reducing its intervention in one of the most critical sectors of the economy.

The increase in allocation for institutional credit to Rs 20 lakh crore in UB 2023-24 from Rs 18.6 lakh crore in UB 2021-22 is in the right direction. But the marginal increase in institutional credit is insufficient for the sector when around 60% of the population still relies on it. Further, an increase in allocation will not help the small and marginal farmers when their borrowing is mainly from the informal sector.

The government, in the present Budget, has given much attention to organic and natural farming, which reported only a 3% share in the country’s net sown area. India has the largest population in the world, and focusing more on organic farming may not be the best way to food security. It would have been better if the government had prioritised promoting contract farmers in all the States to connect small and marginal farmers with the global markets. The government should have given more importance to establishing a proper institutional framework for helping such farmers.

Making India a global millet hub and increasing the agricultural sector’s storage facility would help farmers diversify their cropping pattern.

By slashing the budget for agriculture, it would be difficult to create an alternative market for farmers, double farmers’ income, increase the share of commercial crops, reduce the risk of cultivation, and, more importantly, connect our small and marginal farmers to the global markets. This shows that the agricultural sector has been completely neglected in this union Budget.

- Tags

- India

- Union Budget

Related News

-

Pakistan declares ‘open war’ after strikes on Afghanistan

3 mins ago -

‘Truth always prevails’: Arvind Kejriwal’s wife on Delhi court decision in excise policy case

5 mins ago -

Oppn leaders hail relief for Kejriwal, Sisodia in Delhi excise policy case

10 mins ago -

Newly married man killed hours after wedding in suspected honour killing in Andhra

15 mins ago -

“No difference between BJP and Congress”: Akbaruddin Owaisi’s remark triggers uproar

23 mins ago -

Kejriwal breaks down after court discharge in excise policy case; Sisodia consoles him

40 mins ago -

Arvind Kejriwal discharged in excise case, calls it ‘biggest political conspiracy

39 mins ago -

Congress leader Chennithala alleges data leak of one crore Keralites by CMO

54 mins ago