Opinion: And the Animal asked the Human…

If all lifeforms have sentience and emotion, then the chance to flourish cannot belong to humans alone

By Pramod K Nayar

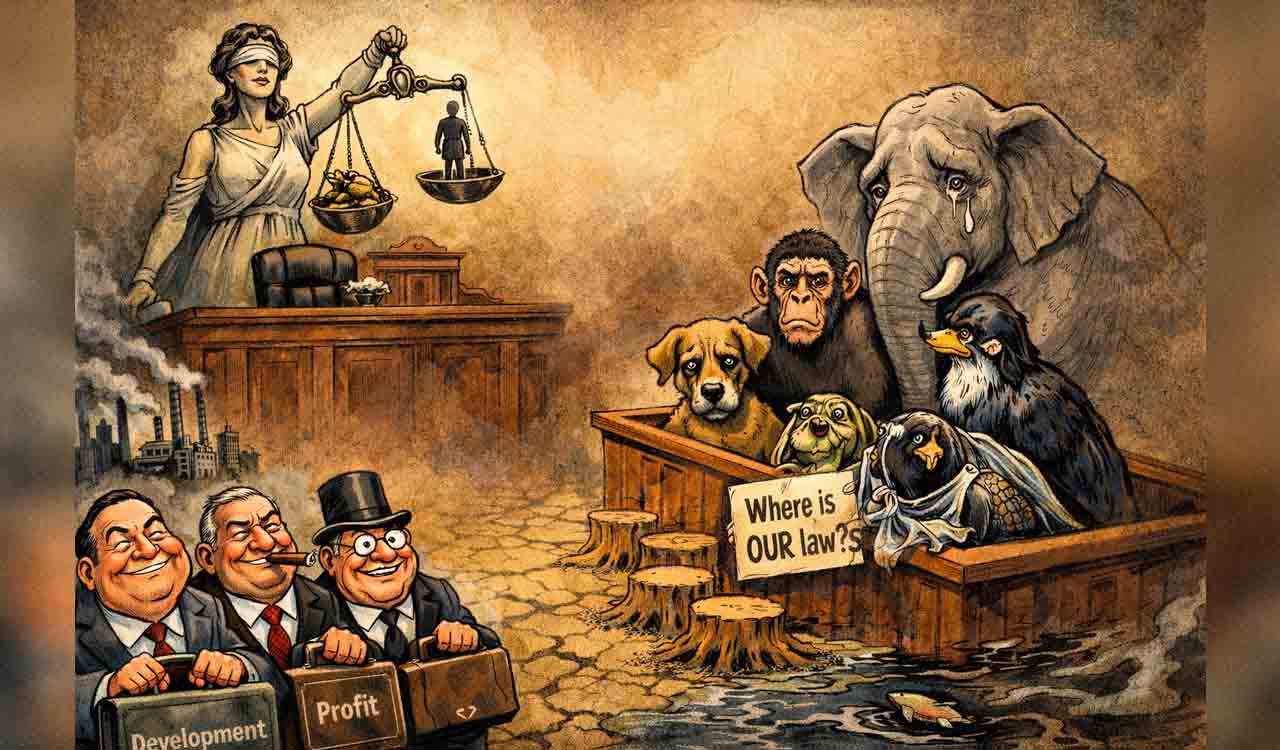

When a human feels her rights have been denied or violated, we have a mechanism to seek redress: the law. Even if the law itself is on occasion responsible for perceived violations — such as exclusion from lists of citizens — the species relies on the law as a mechanism to which an address may be made. Through history we meet lifeforms denied freedom, autonomy, and even the right to live as their species are wont to do because humans have intervened in their living. Let us imagine then — after all, humans are proud of our capacity to imagine — the animals ask: where and to whom do we turn in the context of such violations?

Different Animals

Since antiquity, companion and domesticated animals — dogs, cattle, horses — have received better ‘treatment’ from humans for utilitarian reasons. Some lifeforms have been given privileged status by humans because humanity has more knowledge of their intelligence, tool use, etc.

But in the last century, ethology and various sciences have added to the fund of human knowledge about numerous forms such as the cephalopods and birds. This knowledge about their abilities of perception, emotion, kinship behaviour has, or ought to, enable us to rethink the nature of these lifeforms because, like humans or primates, they exhibit a range of cognitive, perceptual and emotional responses.

In terms of emotion, the ecologist Almo Farina and environmental scientist Philip James have argued that the fear of humans alters the behaviour of lifeforms thus producing what they call a ‘landscape of fear’:

the fear of humans as apex predators modifies the perception of the surroundings and several consequent actions…

Organisms communicate their fear of the landscape to other members of their group. That is, there is emotion but also the transmission of emotion in some representational form or the other — the subject of Richard Powers’ key text The Overstory — so that we cannot argue that nonhuman lifeforms are lower than humans in these domains.

That is, it is not only primates or whales that ought to figure in our imagination of ‘creatures like us’. Research findings tell us that even those unlike us are complex and sentient lifeforms, and hence terms like ‘animality’ or ‘beasts’ that are employed to position these lifeforms as radically distinct from us need to be reconsidered.

Language of the Law

If humans turn to the law as a last resort for justice, other lifeforms clearly have no such resort. But human laws also emerge in specific cultural and social contexts. As the philosopher Martha Nussbaum points out in her work on animal rights and justice:

Law is built by humans using the theories they have. When those theories were racist, laws were racist. When theories of sex and gender excluded women, so too did law … that most political thought by humans the world over has been human-centered, excluding animals. Even the theories that purport to offer help in the struggle against abuse are deeply defective, built on an inadequate picture of animal lives and animal striving.

Nussbaum also notes that if justice and the law are designed, or ought to be designed, to enable sentient humans to reach the full extent of their capabilities, then what prevents us from making a similar argument about nonhuman life forms?

each sentient creature (capable of having a subjective point of view on the world and feeling pain and pleasure) should have the opportunity to flourish in the form of life characteristic for that creature.

The contrast, she writes, is between ‘flourishing lives and impeded lives’. If all lifeforms have a certain form of sentience, communicative abilities and even emotion, then all should have the chance to flourish and not to have their course of life interfered with.

As if We Were Animals…

It is natural, so to speak, that animal lives encounter threats, obstacles and conditions inimical to their flourishing and even survival. For example, changes in weather, shortage of food or predators are definite obstacles to the animal’s routine. A predator may, for instance, intervene in the animal’s life — but this is what is innate to the predator. Or rather, it is not wrong that one creature intervenes in another’s existence because that is the relationship between predator and prey, or the various species within the food chain.

If we see all nonhumans as sentient, then locking them away, denying food or violating their space — which if we do to another human would be criminal — must also count as injustice

However, in the age of anthropogenic changes to the planet, there is no landscape, water body or lifeform that has not been impacted — mostly adversely — by human activities. Which means, it is not necessarily other lifeforms or a storm that makes flourishing or survival difficult for the lifeform: it is humanity.

And this is where the arguments made by philosophers like Cora Diamond and Martha Nussbaum come in. If a lifeform’s living has been interfered with by humans, so Nussbaum argues, then this interference is wrong, and is in the realm of injustice. Animals who choke on plastic or die of oil spillage have had their ecosystems, habitats, habits and therefore their lives interfered with by humans. If the harm is foreseeable — for example, do we not know where the plastics end up? — then there is all the more reason to see human actions as wrong and as instances of injustice to another lifeform.

The erosion of habitats of multiple species is founded on the assumption of the binary: us humans versus them animals, as though the differences are more important than the similarities. When we decide the streets, the lakes, the seas are human territory even though places like the sea are non-anthropic (in which humans cannot live unassisted), then we effectively take away the habitat and therefore life choices of the nonhuman. This would qualify as injustice. We return to Nussbaum:

Injustice depends on the action taken against a sentient being, not on the type of being … In most cases of deliberate wrongdoing, the perpetrator is human, because humans are capable of deliberate malevolent intent in a way that few animals are.

Thus, the sentient creature may be an elephant, a chimp or, of course, a dog. We cannot and need not limit our concern to creatures who have a close evolutionary relationship with humans, if we start with the assumption that sentience is adequate enough to speak of similarities.

If we see all nonhumans as sentient, then locking them away, denying food or violating their space — which if we do to another human would be criminal — would be injustice. To thwart the flourishing of fellow humans is deemed to be injustice, and our heinous acts are called ‘animalistic’. But if we are (like) animals too, then perhaps definitions of injustice ought to expand to include what we humans do to other lifeforms.

The animal asks: is personhood dependent on moral standing, and is this exclusive to humans? How we respond to this question will determine the fates, inside courts and outside, of those who walk with us.

(The author is Senior Professor of English and UNESCO Chair in Vulnerability Studies at the University of Hyderabad. He is also a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society and The English Association, UK)

Related News

-

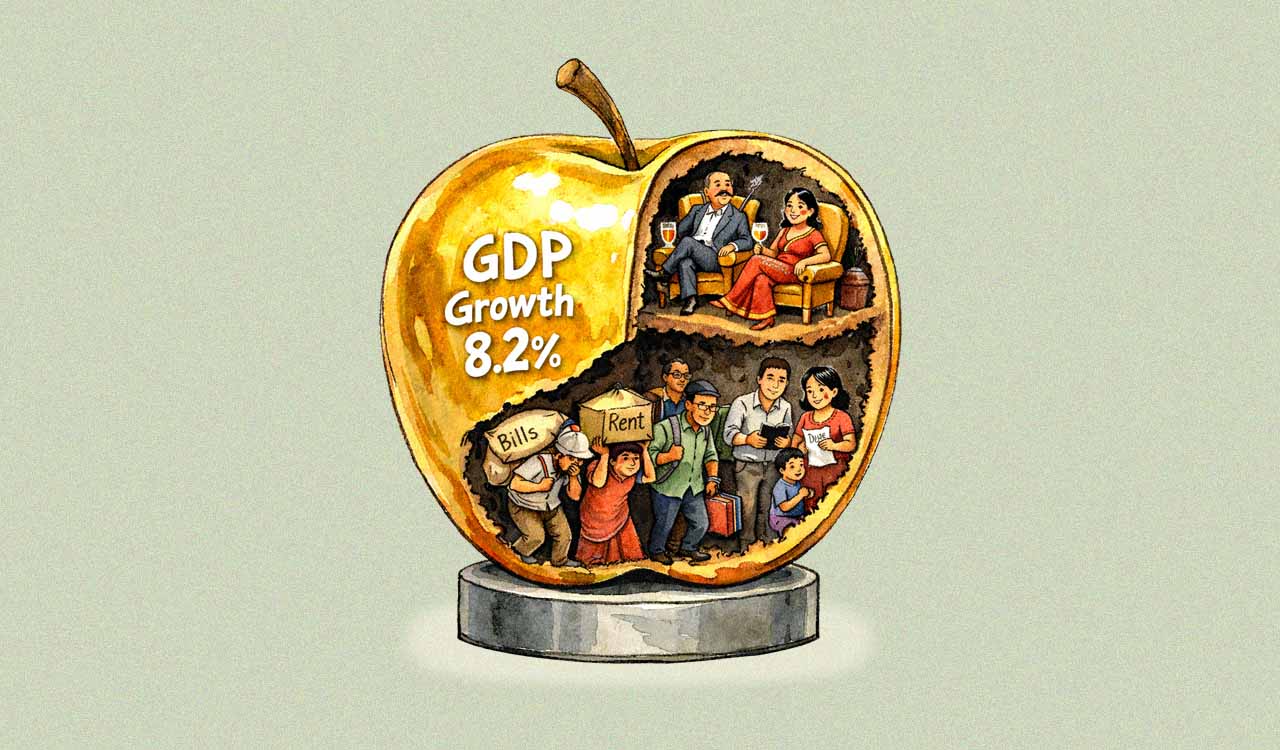

Opinion: India’s subsidy rationalisation: Fiscal discipline vs social protection

-

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

Van overturns after tyre burst, 15 wedding guests injured in Nirmal

2 mins ago -

Gold slips on strong dollar, silver rebounds on MCX; Rupee hits record low

4 mins ago -

Young government job aspirant dies by suicide in Mancherial

4 mins ago -

KTR pays last respects to Kavuri Sambasiva Rao

8 mins ago -

Baloch militant group vandalises gas pipeline transporting fuel to Karachi

12 mins ago -

Licensed surveyors meet KTR, complain of no work or salary

15 mins ago -

Gulf crisis: GAIL halts gas supply to Yelahanka power plant; generation may be hit

25 mins ago -

Khot Lakhpat, Attock camps reactivate as Khalistani groups eye narco funding

38 mins ago