Opinion: Bangladesh crisis a regional stress test – Why India cannot afford to look away

New Delhi’s response will shape not only the future of its eastern neighbour but also security of South Asia

By Brig Advitya Madan

Bangladesh is once again at a dangerous inflection point. What began as a student-led uprising in July 2024, which ultimately forced Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina to flee to India, has now morphed into a far more volatile and unpredictable phase. The killing of Sharif Osman Hadi — one of the most prominent faces of that movement — has acted as fresh tinder in an already combustible political landscape. For India, this is not merely a neighbourhood crisis. It is a strategic warning that demands urgent attention.

Also Read

To briefly recall the backdrop: the July 2024 students’ movement shook Bangladesh to its core. Anger over governance failures, economic stress and political repression spilt onto the streets. The crackdown was brutal — nearly 1,400 people lost their lives — and eventually culminated in Sheikh Hasina seeking refuge in India. The aftermath left Bangladesh politically fractured, socially polarised and institutionally fragile.

On the Boil Again

The current unrest has been triggered by the assassination of Sharif Osman Hadi, a 32-year-old leader of the student movement and spokesperson of Inqlab Mancha. Hadi was not just an activist; he had emerged as a symbol of a new political generation and was also a candidate in the elections-cum-referendum scheduled for February 12, 2026.

On December 8, while campaigning in Bijoynagar, he was shot in the head by masked gunmen. Airlifted to Singapore for treatment, Hadi succumbed to his injuries on December 18. His burial on December 20 — on the Dhaka University campus, near the mosque adjacent to the tomb of Bangladesh’s national poet Kazi Nazrul Islam— was a powerful, emotive moment. It was attended by interim leader Muhammad Yunus, Army chief General Wakar Zaman, and representatives of major political formations, including the BNP and the National Citizen Party.

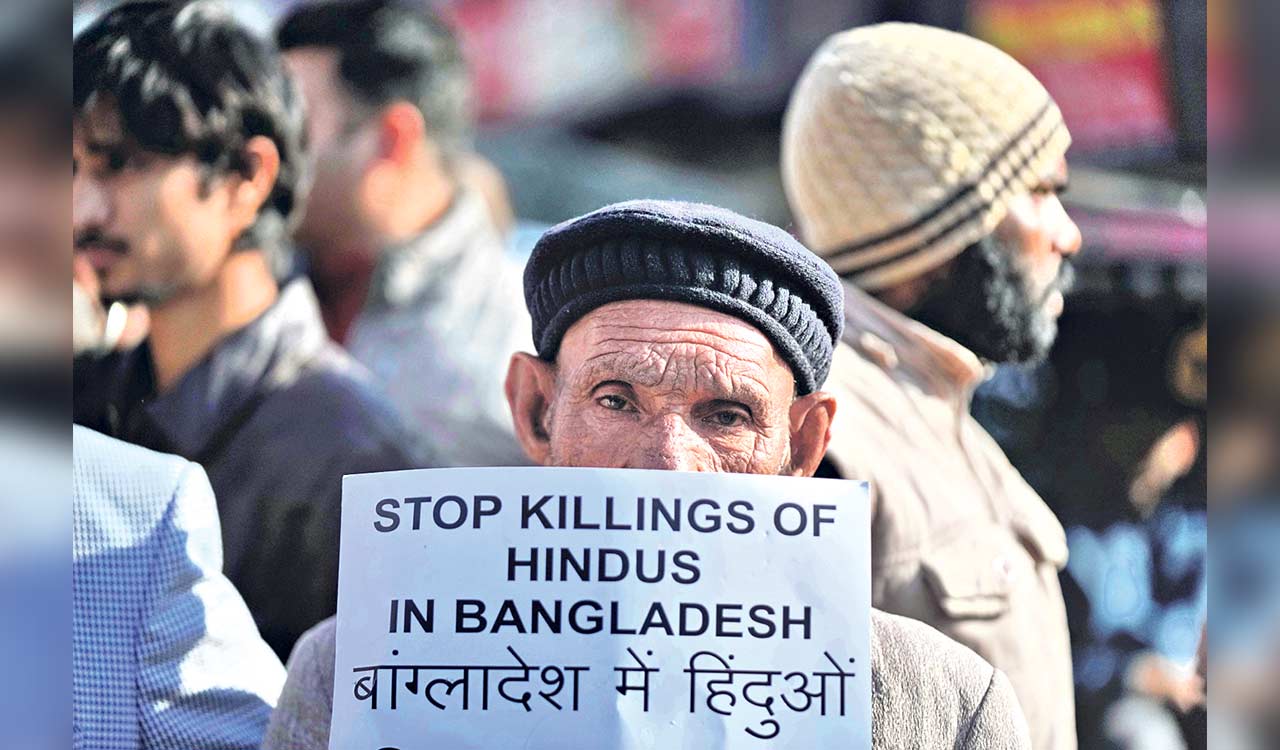

The state declared official mourning. Inqlab Mancha issued a 24-hour ultimatum demanding justice. Ten suspects were arrested — seven by the Rapid Action Battalion and three by the police. But instead of calming tempers, the developments unleashed a wave of violence and mob fury. The house of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was vandalised, Awami League offices were attacked, and even media institutions such as The Daily Star and Prothom Alo were targeted. Stones were hurled at the residence of India’s Assistant High Commissioner. In one of the most disturbing incidents, a young Hindu man, Dipu Chandra Das, was lynched and burnt alive in Mymensingh.

At the heart of the crisis lies the failure of the interim dispensation under Muhammad Yunus to assert control. The vacuum has been swiftly exploited by hostile external actors — most notably Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). Since October 2024, there have been multiple visits by senior Pakistani intelligence officials and politicians to Bangladesh. This is not a coincidence; it is classic deep-state opportunism. Anti-India sentiment is being deliberately stoked, with rumours circulating that Hadi’s killers have fled to India. Such narratives are tailor-made for manipulation by both Pakistan and China, each eager to expand its footprint in South Asia at India’s expense.

Implications for India

For New Delhi, the implications are severe. India shares a 4,096-kilometre border with Bangladesh —much of it porous and inadequately fenced — touching seven northeastern States. Any prolonged instability in Bangladesh is a godsend for insurgent groups operating in India’s Northeast.

Having served in the region, I can attest that outfits such as ULFA, the National Democratic Front of Bodoland and the National Liberation Front of Tripura have historically maintained camps across the border in Bangladesh. Many radical elements in the region have established links with Pakistan-based terror groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba and, by extension, the ISI.

The demographic dimension is equally worrying. Bangladesh is home to around 13.1 million Hindus — roughly 8 per cent of its population — making it the third-largest Hindu population in the world. Rising communal violence could trigger a refugee influx reminiscent of 1971, with destabilising consequences for Assam, West Bengal, Tripura and beyond.

Reports of the BSF recently pushing back nearly 1,000 Hindu migrants from the Bangladesh Rifles sector in Cooch Behar underscore the scale of the looming humanitarian and security challenge. Add to this the risks of increased drug trafficking, cattle smuggling and arms movement, and the picture grows darker.

Bilateral Agreements

Strategically, instability in Bangladesh also threatens critical bilateral agreements. The Teesta river water-sharing agreement, concluded in 2011, allocates 42.5 per cent of the water to India, 37.5 per cent to Bangladesh, with the remaining 20 per cent allowed to flow freely. A hostile or unstable regime in Dhaka could jeopardise this delicate arrangement. Even more vital is the Siliguri Corridor — the so-called “Chicken’s Neck”—which connects mainland India to the Northeast. Any disruption in Bangladesh amplifies vulnerabilities around this narrow stretch of land.

Compounding these risks is China’s steadily expanding presence in Bangladesh. Beijing has dramatically increased its investments: 27 power projects, 12 highways, 21 bridges spanning 550 km, sewage treatment plants in Dhaka, seven railway lines covering 542 km, and over 260 Chinese firms employing nearly 5.5 lakh people. Bangladesh is an active partner in China’s Belt and Road Initiative and currently owes Beijing an estimated USD 17.5 billion. This economic embrace inevitably translates into strategic leverage — often at odds with India’s interests.

India, therefore, cannot afford complacency. First, border management must be strengthened urgently, including accelerated fencing and enhanced surveillance. Second, New Delhi must leverage its diplomatic capital — working with the US, the UK and the European Union — to ensure Bangladesh does not slide into the orbit of Pakistan-China strategic collusion. Third, India should support democratic stability in Bangladesh without being seen as partisan, while firmly countering disinformation and anti-India propaganda.

Bangladesh’s crisis is not an isolated tragedy; it is a regional stress test. How India responds — quietly, firmly and strategically — will shape not only the future of its eastern neighbour but also the security architecture of South Asia. Silence or delay is not an option.

(The author is a retired Army officer)

Related News

-

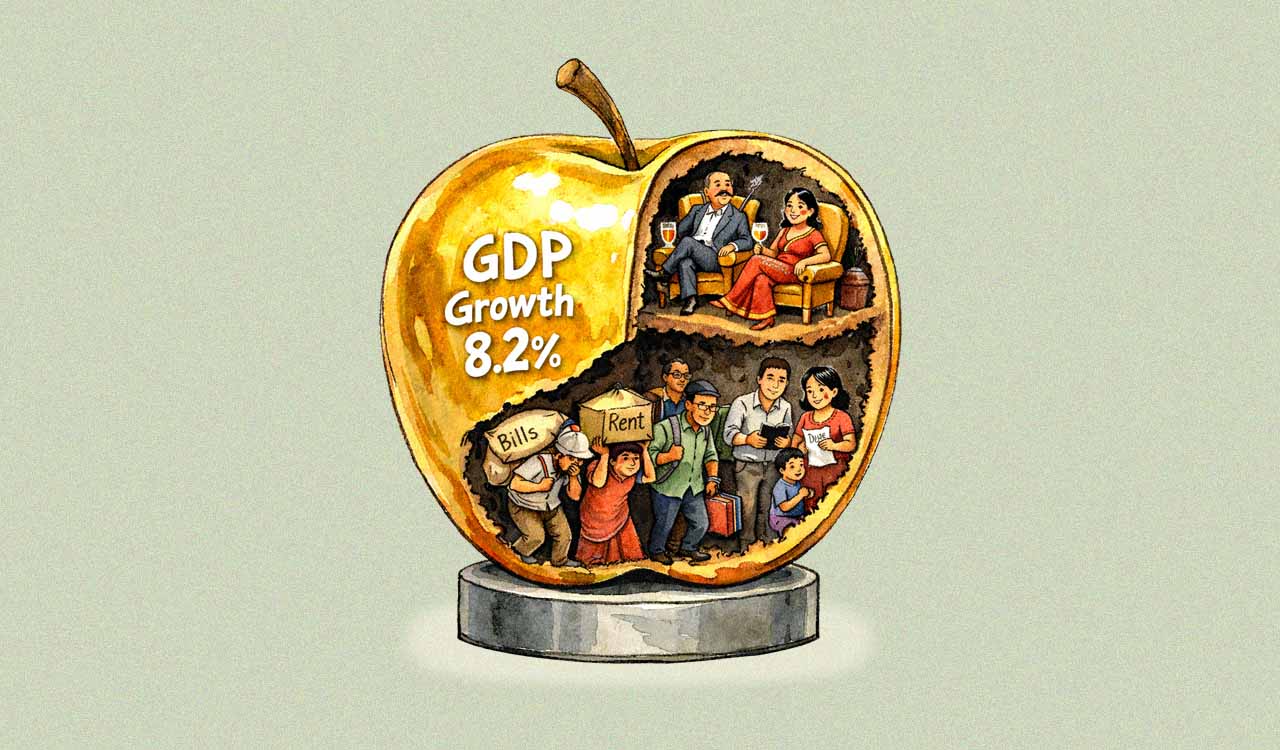

Opinion: India’s subsidy rationalisation: Fiscal discipline vs social protection

-

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Bengal STF arrests two in Osman Hadi assassination case near Indo-Bangla border

-

SCR RPF rescues 92 children under ‘Nanhe Farishte’ operation in February

29 mins ago -

Inorbit Mall Cyberabad hosts live Qawwali, classical music events in March

59 mins ago -

BIMTECH partners with Hexalog to launch Centre of Excellence in supply chain & logistics

1 hour ago -

Emerging technologies like quantum computing and HPC set to transform startups and enterprises

1 hour ago -

KTR distributes Ramzan ration kits, targets Congress over welfare schemes

1 hour ago -

ITC Mission Sunehra Kal organises Water Mela in Bhadrachalam to promote water conservation

1 hour ago -

India emerges as third-largest cross-border hiring pool: Report

2 hours ago -

Two held with 1.74 kg ganja in Hyderabad’s Attapur

2 hours ago