Opinion: Big energy, bigger risks — opening up India’s nuclear power

The SHANTI Act 2025 opens the door to private nuclear investment while raising serious questions about liability limits, regulatory independence, and public risk

By Atul Kriti, Bhabya, Balhasan Ali

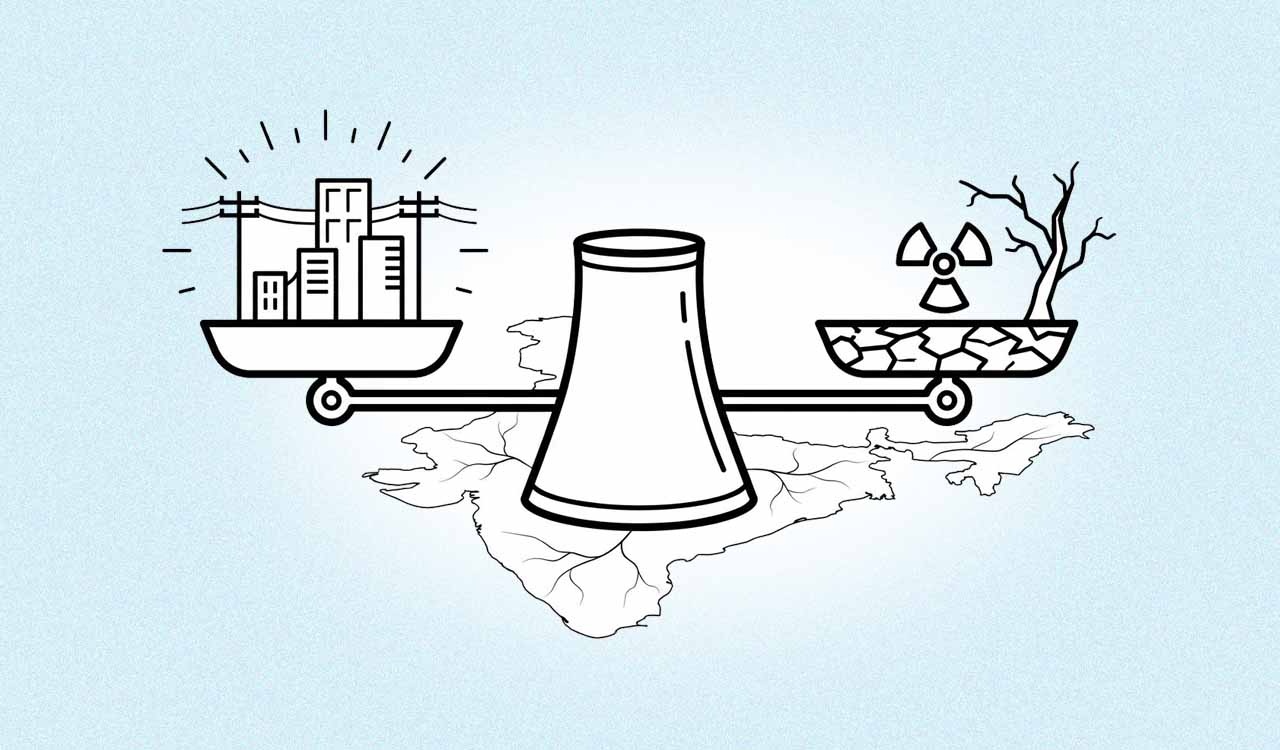

In December, Parliament passed the Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India (SHANTI) Act, 2025, reshaping India’s nuclear framework after nearly seven decades. For the first time since independence, private companies can now build and operate nuclear reactors. The law repeals the 1962 Atomic Energy Act and supersedes the 2010 Civil Liability for Nuclear Damage Act. The government hailed it as a watershed moment for clean energy. Yet examining its provisions raises significant questions about whether it truly balances the need for investment with adequate protection of public interests.

India’s energy challenge is undeniable. Nuclear power currently contributes 8.8 GW to the installed capacity, accounting for 3.1% of the total electricity generation. (Department of Atomic Energy data for FY 25) The government plans to expand this to 100 gigawatts by 2047, which is essential for meeting its net-zero emissions targets.

Realising this ambition requires mobilising Rs 15–20 lakh crore in investment. Since the public exchequer cannot sustain this burden alone, permitting private participation represents a rational policy response. Yet critical infrastructure carrying existential risk demands equally rigorous attention to safeguards, accountability mechanisms, and democratic oversight.

Where Risk Falls

The Act establishes tiered operator liability, with Rs 100 crore for small reactors and Rs 3,000 crore for large installations. Beyond these caps, a central Nuclear Liability Fund covers remaining costs. Two-tier liability models are designed to expedite victim compensation by minimising prolonged litigation. France and the United States employ similar structures. However, this framework raises concerns about risk allocation. India’s constitutional jurisprudence, established in MC Mehta v Union of India (1987), established the doctrine of Absolute Liability.

While the ‘polluter pays’ principle is often cited, the concept was officially adopted into Indian environmental law in 1996. The 1987 ruling specifically mandated that enterprises engaged in hazardous activities are fully responsible for any harm caused, regardless of whether they took reasonable precautions. The SHANTI Act introduces liability caps that create asymmetry with this principle.

Consider a concrete scenario: a private operator runs a reactor for 40 years, earning substantial profits. If an accident causes Rs 8,000 crore in damages, the operator pays Rs 3,000 crore and incurs no further liability. The remaining Rs 5,000 crore becomes public responsibility. Profits flow to investors; citizens bear residual losses.

International experience warrants attention. Fukushima’s cleanup costs exceed $180 billion, illustrating the magnitude of tail risks that remain within the realm of possibility. India’s cap of Rs 3,000 crore amounts to just 0.2% of that burden. The government could have addressed these concerns through automatic liability escalation indexed to inflation, mandatory decommissioning funds (as France and the US require), and explicit inclusion of non-radiological damages such as thermal pollution, losses in agricultural productivity, and chronic health effects arising from long-term low-level radiation exposure. The current framework excludes these categories. These exclusions represent policy choices, not technical necessities.

Environmental Oversight

The Act elevates the Atomic Energy Regulatory Board (AERB) to statutory status, requiring it to report directly to Parliament. Independent regulators with transparent mandates strengthen safety cultures, and this institutional change merits recognition. However, statutory designation does not guarantee meaningful independence. The law is silent on appointment procedures, staff protections from arbitrary termination, budgetary autonomy independent of executive discretion, and insulation from ministerial direction. These procedural safeguards are essential for converting formal independence into substantive autonomy.

The appeals mechanism also warrants examination. Challenges to AERB decisions are first heard by the Atomic Energy Redressal Advisory Council. The claim of “direct” and independent oversight is weakened by the fact that the Council is chaired by the Chairperson of the Atomic Energy Commission — the same body responsible for promoting nuclear policy and development. This arrangement creates institutional overlap rather than external review. Allowing direct appeals to the Supreme Court with quarterly parliamentary oversight would better ensure genuine structural separation.

Fukushima’s cleanup has exceeded $180 billion, a reminder that even low-probability nuclear accidents can impose catastrophic costs, which India’s new liability framework may be ill-equipped to absorb

Moreover, AERB remains substantially under-resourced. With limited inspectorate capacity, it may face constraints as private operators proliferate across dispersed sites. Enhanced budgetary allocation for recruitment, scientific expertise, and competitive compensation would strengthen regulatory effectiveness.

Section 87 grants SHANTI supremacy over conflicting legislation. While this streamlines implementation, it risks sidelining environmental oversight. Nuclear facilities consume vast amounts of freshwater, discharge thermal pollution, occupy ecologically sensitive land, and generate waste that requires secure storage for thousands of years. India’s environmental regulatory framework, comprising the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act of 1974, the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act of 1981, the Indian Forest Act of 1927, the Coastal Regulation Zone notification of 1991, and the Biological Diversity Act of 2002, imposes specific operational constraints.

State pollution control boards, forest departments, and coastal authorities currently exercise supervisory functions over their respective areas. Invocation of SHANTI’s supremacy clause risks relegating these environmental agencies to a secondary role. By contrast, Finland, Sweden, France, and the United States mandate parallel environmental and nuclear reviews, with both authorities retaining independent denial powers. These models promote integrated rather than hierarchical oversight.

Democratic Accountability

A related concern involves information access. Section 39 allows broad categories of information to be designated as “restricted,” exempting them from the Right to Information Act without any balancing tests or appeal mechanisms. Once designated, data on nuclear material locations, reactor designs, and inspection reports are entirely removed from public scrutiny. This opacity is particularly dangerous as private operators enter the sector. Information asymmetry has historically facilitated regulatory capture; when citizens and civil society cannot examine compliance, accountability and oversight weaken.

The SHANTI Act also bypasses standing committee scrutiny. Transformational legislation affecting critical infrastructure typically undergoes detailed parliamentary examination. Such deliberation enables scientific institutions, environmental groups, and affected communities to present evidence, flag technical concerns, and identify unintended consequences.

Necessary Refinements

The Act addresses real financing constraints, and private participation is a defensible policy. Nevertheless, governance could be substantially strengthened through targeted refinements: automatic liability escalation indexed to inflation; mandatory decommissioning funds; transparent regulatory appointment and removal procedures; independent budgetary allocations; quarterly parliamentary oversight; direct appeals to the Supreme Court; parallel environmental reviews with independent agency veto authority; amend Section 39 to retain RTI exemptions, with a public-interest override; and enhanced regulatory capacity through additional inspectors and competitive recruitment.

Regulatory independence, though formally strengthened, remains procedurally vulnerable. Environmental oversight continues to operate hierarchically while information access is constrained by blanket exemptions. These are not inevitable consequences of privatisation; they reflect policy choices. Subordinate legislation, rules, and administrative practice can substantially address these gaps.

Whether governance evolves in this direction will depend on the commitment of government, regulators, and civil society to enforce safeguards that may, occasionally, slow nuclear development to strengthen accountability. The coming years will determine whether the SHANTI Act enables clean energy expansion with adequate public protection or becomes a template where growth repeatedly takes precedence over governance rigour.

(Atul Kriti is a PhD Research Scholar at Tata Institute of Social Sciences [TISS], Hyderabad. Bhabya is a Young Professional-II (AICRP-WIA) at Govind Ballabh Pant University of Agriculture and Technology, Uttarakhand. Dr Balhasan Ali is Assistant Professor at TISS, Hyderabad. Views are personal)

Related News

-

Four injured in helium balloon explosion

53 seconds ago -

Fish to replace chicken served in midday meals in Govt. schools: minister Srihari

20 mins ago -

Slum voters made Prakash Goud MLA, not apartment residents: Revanth Reddy

28 mins ago -

Govt to use all policy tools to support exporters amid West Asia crisis

39 mins ago -

Nearly 100 ceramic units shut in Morbi due to fuel supply disruption

46 mins ago -

JD(U) workers protest Nitish Kumar’s move to Rajya Sabha

50 mins ago -

Siddaramaiah says govt aims to make Bengaluru world’s most liveable city

1 hour ago -

BRS demands Rs 1 crore ex-gratia for Tolichowki tragedy victims

1 hour ago