Opinion: Delimitation, another assault on India’s federalism

Punishing successful States and rewarding the failed ones will further widen the fissure between North and South

By Geetartha Pathak

The issue of delimitation or redrawing of electoral seats to reflect changes in population over time has emerged as a big political storm in India, the first wave of which has already hit the South Indian States.

Also Read

“The essence of India’s democracy rests on its federal character — a system that gives each State its rightful voice while honouring our sacred unity as one nation,” said Tamil Nadu Chief Minister and DMK Chief MK Stalin in a letter to Chief Ministers and former Chief Ministers. He termed the Union government’s delimitation plans as a fundamental assault on federalism.

Redrawing of parliamentary and Assembly constituency boundaries within each State or increasing the number of Assembly seats for any State is a routine exercise which does not affect the federal balance. However, the present concern is the reapportionment of seats on the basis of population for different States and Union Territories, which has been frozen since 1976.

One person, One vote, One value

We have three options — extend the freeze beyond 2026, unfreeze it or opt for a permanent freeze. We can also adopt a compromise formula as adopted by the United States. Regular revision of electoral constituencies is based on the principle of “One person, one vote, one value”. This basic democratic principle mandates that each member of a legislature must represent approximately the same number of persons, violations of which may result in less value of vote in large constituencies than that of those in smaller constituencies.

However, there are constituencies with less than 8 lakh votes in Goa and Arunachal Pradesh as a special provision to safeguard the representation of smaller States. This is a deviation from the normal democratic principle for bringing a balance in a federal structure.

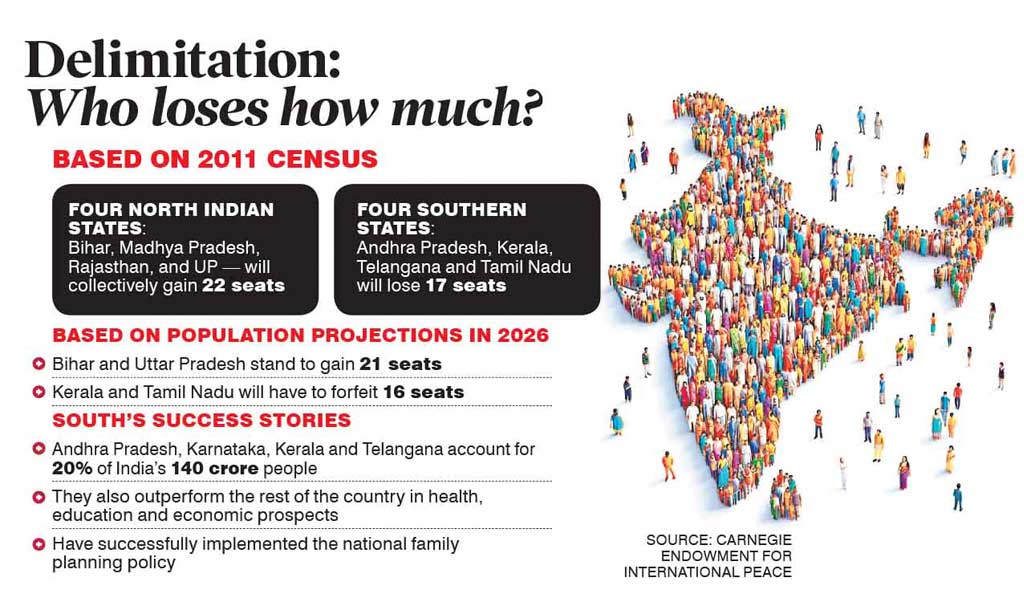

Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Telangana — these four States account for 20% of India’s 140 crore people. They also outperform the rest of the country in health, education and economic prospects. They successfully implemented the national family planning policy. Punishing the successful States and rewarding the failed ones in the delimitation process is now an embroiling issue that will widen the fissure between the North and the South.

Constitution Mandates

The Constitution mandates that seats be allocated to each State based on its population, with constituencies of roughly equal number of voters. Reallocation of seats after each census, reflecting updated population figures, is also mandated by the Constitution. Accordingly, parliamentary constituencies were redrawn three times based on the decennial census in 1951, 1961 and 1971.

This exercise was paused after the central government announced formal National Population Policy, 1976, which aimed to address population growth through measures like raising the minimum marriage age and promoting family planning, to avoid an imbalance of representation. The next delimitation exercise is set for 2026, but uncertainty looms as India has not conducted a census due in 2021, citing the Covid pandemic. There is no clear timeline as to when it will take place. If it is held after 2026, the delimitation will follow based on that census.

The Loss

According to research done by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, four north Indian States (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh) would collectively gain 22 seats, while four southern States (Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Telangana and Tamil Nadu) would lose 17 seats based on population in 2011 census.

Based on its population projections in 2026, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh alone stand to gain 21 seats while Kerala and Tamil Nadu will have to forfeit as many as 16.

Union Home Minister Amit Shah said on February 26, 2025, that southern States will not be affected by the delimitation exercise. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has ensured that not a single Lok Sabha seat is going to be reduced on a pro-rata basis, said Shah. He also promised that the southern States would get their rightful share of any increase in seats.

Parliamentary constituencies were redrawn three times till 1971, but was paused after the central government announced National Population Policy, 1976, which aimed to address population growth

However, without increasing the total number of seats, it is impossible to retain the same number of seats for the southern States. And to increase the strength of Parliament, an Amendment to Article 81 of the Constitution will be required. If reapportionment is done keeping the total number of seats at 543, seats for southern States will be reduced to 103 from the present 129, a loss of 26 seats.

If we assume that the total number of seats in Parliament is increased to 888, as the provision of a total 888 number of parliamentarians in the newly constructed parliament building suggests, and the total number of seats for southern States remained constant at 129, yet their proportionate representation will be reduced substantially. The wealth gap between the States has already weakened federalism. Now the disparity in representation in Parliament will be another blow to Indian federalism.

World Over

The United States Constitution incorporates the result of the Great Compromise or Sherman Compromise, which was an agreement reached during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. It established representation for the US Senate. Each State was equally represented in the Senate with two representatives, irrespective of the population.

The founding fathers of the US Constitution included a clause in the Constitution to prohibit any State from being deprived of equal representation in the Senate without its permission. For this reason, “one person, one vote” has never been implemented in the Senate, in terms of representation by States.

In Australia, ‘one vote, one value’ is a democratic principle, applied in electoral laws governing redistributions of electoral divisions of the House of Representatives. Under this, all electoral divisions have the same number of enrolled voters, within a specified percentage of variance. The principle does not apply to the Senate because, under the Australian Constitution, each State is entitled to the same number of senators, irrespective of the population of the State.

India has the dubious distinction of postponing disputes without immediately resolving the issues. Shortsightedness and desire for immediate political gain make Indian politicians push controversies to be tackled by later generations. Reservation for jobs and educational institutions for socially deprived and backward classes, which was to end after ten years, has indefinitely continued.

The issue of delimitation and ‘one person, one vote, one value’ was resolved in the United States as early as 1787. We, however, are still struggling.

(The author is a senior journalist from Assam)

Related News

-

Opinion: India’s ‘Goldilocks’ growth and the silent struggle of its working class

-

Opinion: Time to ban paraquat — the poison without an antidote

-

Amit Shah likely to reply to debate on no-confidence motion against Om Birla

-

Opinion: Telangana must increase public spending on education to build human capital

-

SICA hosts memorial Carnatic concert in Hyderabad

4 hours ago -

National IP Yatra-2026 concludes at SR University in Warangal

4 hours ago -

Iran war may push fuel prices up: Harish Rao

4 hours ago -

Rising heat suspected in mass chicken deaths at Siddipet poultry farm

4 hours ago -

Annual General Body Meeting of the Rugby Association of Telangana held

5 hours ago -

Godavari Pushkaralu to be organised on the lines of Kumbh Mela: Sridhar Babu

5 hours ago -

Para shuttler Krishna Nagar clinches ‘double’ in 7th Senior Nationals

5 hours ago -

Madhusudan clinches ‘triple’ crown in ITF tennis championship

5 hours ago