Opinion: What India can learn from Jewish diaspora

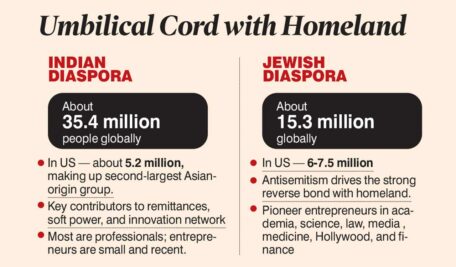

Indian diaspora numbers must be coupled with narrative, unity, and institutions to convert potential into power

By T Muralidharan

Diaspora communities shape nations far beyond their borders. Among the largest and most influential diasporas in the world today are the Indians and the Jews. Both have left deep marks on politics, economics, and cultural landscapes in the United States and globally. Yet their experiences, identity negotiations, and power projection strategies have been remarkably different.

Also Read

The State of Israel and the Jewish diaspora have a symbiotic relationship. Diaspora Jews were central actors in lobbying for US recognition of Israel in 1948, in fundraising, shaping US foreign aid, and sustaining Israel’s international legitimacy. Over decades, institutions such as AIPAC (American Israel Public Affairs Committee) have given the US Jewish community a powerful lever in Washington.

Founded in 1951 as the American Zionist Committee for Public Affairs, AIPAC today is one of the most influential pro-Israel lobbying groups — spending heavily in US elections, backing pro-Israel candidates, and influencing congressional foreign-policy outcomes.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s outreach stands out for its intensity. Flagship diaspora events (eg, ‘Howdy, Modi’ in Houston, ‘Namaste Trump’ rallies) aimed to mobilise global Indians aggressively. However, critics argue that the outreach is event-centric and lacks sustainability. Many in the Indian diaspora feel that India views them instrumentally —as useful for financial gain or soft power, but not as equal stakeholders.

Migration, Settlement

Jewish immigration to the United States came in successive waves beginning in the late 19th and early 20th centuries — from Eastern Europe, Russia, and Germany — often driven by persecution, pogroms, and forced displacement. Over time, these communities established roots and became multigenerational, resulting in deep institutional embedding in US life. The founding of Israel in 1948 created a powerful homeland focus that merged diaspora identity with a territorial nation.

Indian migration, by contrast, is a more recent phenomenon. Until the 1965 US Immigration and Nationality Act, Indian immigration was severely restricted. After 1965, educated professionals began to come, and the wave accelerated further in the 1990s with the rise of IT, H-1B visas, outsourcing, and global mobility. Many Indian Americans today are first-generation, or at best second-generation, and a significant share remain on green cards or long-term visa paths rather than full US citizens.

This time difference matters. The Jewish community has had over a century to build dense institutions, political networks, philanthropic structures, and a unified community identity. Indian-American institutions are still taking shape. The shorter time span means the Indian diaspora is less bonded, less institutionally mature, and more heterogeneous by language, religion, region, and generation.

Contrasting Pictures

The age profiles of the two communities further underline their differences. Indian Americans are strikingly young. Their overall median age is about 34, with immigrants averaging 40 years, while US-born Indian Americans have a median age of just 13.4 years — nearly 60 per cent under 18. This signals a second generation poised to shape American politics, economy, and culture in coming decades, if not now.

By contrast, Jewish Americans have a median age of 49 years, with 29 per cent of adults aged 65 or older. This older age profile reflects a deeply entrenched community with generational wealth and institutional continuity.

The extraordinary weight of Jewish diaspora in US politics, culture, and philanthropy is a remarkable case study on how a smaller, older, and wealthier group can exert disproportionate influence

The economic profile highlights another striking difference. Indian Americans have the highest median household income of any ethnic group in the US at about USD 145,000 — more than double the national median. They dominate STEM fields, medicine, finance, and management.

Jewish Americans report a lower median household income — around $97,000 — but they far surpass Indians in accumulated wealth. The median net worth of Jewish households is estimated at USD 4,43,000.

Indian remittances reflect strong homeland ties, reaching USD135 billion in 2024. On the other hand, Jewish Americans channel wealth into US political funding and philanthropy directed toward Israel.

Identity, Politics, and Lobbying

Identity plays out very differently across the two communities. Kamala Harris, despite her Indian mother, rarely highlights her Indian heritage in political life. Nikki Haley, though of Punjabi Sikh origin, converted to Christianity early and downplayed her ancestry. By contrast, Jewish identity has been integral to political life in America. Jewish Americans openly embrace their heritage and have built institutions such as AIPAC, which has shaped US foreign policy for decades.

Indian politicians have not systematically built a connection with the Indian diaspora. Barring Modi, most Indian leaders maintained weak ties with Indian Americans. The three longest-serving PMs — Jawahar Lal Nehru, Indira Gandhi, and Manmohan Singh — probably had more admirers in England rather than America.

Israel’s early leaders, David Ben-Gurion and Golda Meir, institutionalised lobbying through the Jewish diaspora as a bipartisan, organised force with long-term continuity. Another key factor is the total alignment of Israel with the US. India’s multi-polar and independent foreign policy contrasts sharply with Israel’s, making lobbying among US Congressional leaders and Senators much more difficult.

Race and visibility influence assimilation. Jewish Americans, largely of European descent, were historically able to blend into the white mainstream. Indians, by contrast, stand out more visibly, which can invite both admiration for their professional success and prejudice rooted in racial stereotypes. This visible difference adds complexity to Indian American integration in ways that differ sharply from the Jewish experience.

Voices, Perspectives

Congress leader Shashi Tharoor, having worked at the United Nations for years, notes India’s under-leveraging of its diaspora. Indian Americans often ask what India can do for them, whereas Jewish Americans see their lobbying as strengthening Israel. The gap reflects a lack of institutional support and narrative-building from India compared to Israel’s systematic diaspora engagement.

The Jewish diaspora has long-established institutions, media lobbies, and think tanks in Washington. They have a media-savvy presence. Indian diaspora and India’s US-based advocacy are still maturing. Indian Americans seeking to influence US public opinion must often rely on niche ethnic media or social media to frame their narratives with little national visibility.

Comparative Lessons

The Indian and Jewish American experiences highlight contrasting strengths. Indians are numerous, young, and highly successful in income terms, yet they lack the organisational depth and political unity of Jews. Jewish Americans are fewer but older, wealthier per capita, and vastly more institutionally entrenched. For India, the lesson is clear: diaspora numbers must be coupled with narrative, unity, and institutions to convert potential into power.

In conclusion, the Indian diaspora represents future potential, while the Jewish diaspora represents entrenched influence. If India invests in building institutions and systematic diaspora engagement, its young and successful overseas population could, in time, rival the Jewish diaspora in shaping global perceptions and policy. But the work must begin now.

(The author is an Independent Journalist)

Related News

-

Congress leader moves SEC against party MLA over poll malpractice

8 hours ago -

BRS seeks action against Jagga Reddy, flags counting day threat

8 hours ago -

High voter turnout recorded across 19 municipalities in erstwhile Medak district

9 hours ago -

Salman’s brother-in-law gets threat email; Bishnoi gang link suspected

9 hours ago -

BRS slams police inaction over alleged attack by Jagga Reddy

9 hours ago -

Candidate distributes fake gold coins to lure voters in Sircilla

9 hours ago -

Jagga Reddy blames SEC for Sangareddy polling incident

9 hours ago -

India prepare for Pakistan showdown after Namibia game

9 hours ago