Rewind: Return of the 19th-century — survival of the strongest at Davos

Power is increasingly overriding law, morals, and values, exposing a ‘world without rules’ — an uncomfortable truth revealed as leaders gathered in the Swiss Alps amid rising global tensions

By Dr Anudeep Gujjeti

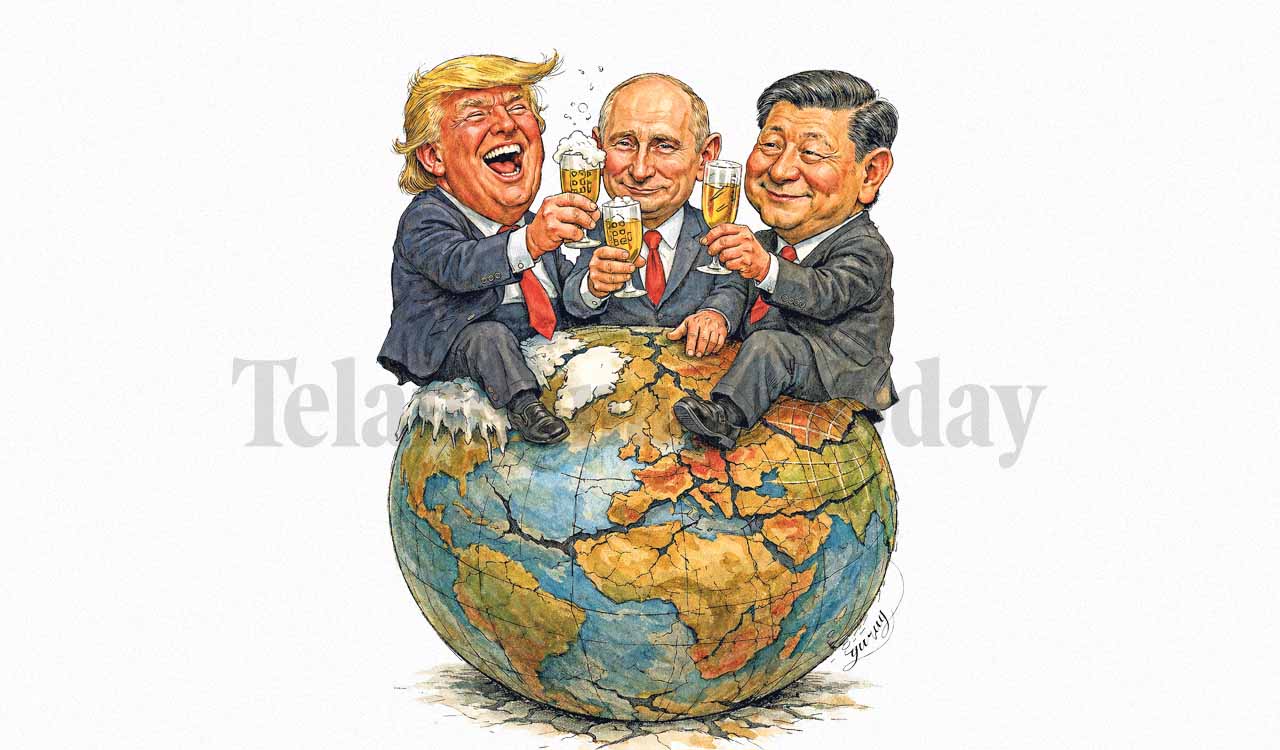

In international politics today, ‘might’ is making a comeback over ‘right’. Across the world, rules and restraints are bending to raw power or being cast aside entirely. The so-called rules-based order endures only so long as it suits the interests of major powers. When it does not, laws and principles are reinterpreted or simply ignored.

Also Read

Recent geopolitical events, from Washington’s revived appetite for territorial deals to Beijing’s coercive campaigns and Moscow’s ongoing war, all point to a world increasingly governed by force and exceptionalism rather than norms. This shift does not signal the total collapse of international law, but its subordination — rules now apply only when power permits, revealing an order less rule-bound than many presumed.

19th Century Redux

An unusual spectre from the 19th century hovered over this year’s World Economic Forum in Davos. The prospect of one country buying part of another resurfaced when United States President Donald Trump reiterated his desire to acquire Greenland, an autonomous Danish territory, even raising the possibility of using tariffs or military force to achieve it. Amid transatlantic criticism, Trump later promised he “would not use force” and claimed to have a “framework of a future deal” for Greenland.

Yet, the episode itself was significant. The leader of the world’s leading power was openly questioning the long-standing norm of territorial sovereignty. That norm, that nations are not for sale or subject to annexation at a great power’s whim, a relic of colonial-era great power politics, has underpinned international law since 1945.

On January 3, the US launched a unilateral operation in Caracas, the Venezuelan capital, to depose President Nicolás Maduro. In a predawn raid, accompanied by missile strikes on military targets, US special forces captured Maduro and his wife and whisked them onto an American naval vessel. The following day, Maduro was in New York, facing US drug-trafficking charges. President Trump announced, without any international mandate, that the US would “run the country” on an interim basis to ensure a “safe” political transition in Venezuela.

A similar logic underpinned Western disengagement from the Kurds in Syria. The US and its European partners justified their withdrawal by arguing that the rationale for the US-SDF partnership, the SDF’s role as the primary anti-ISIS force on the ground, had largely ‘expired,’ leaving Kurdish allies exposed once their strategic utility diminished.

- US President Donald Trump reiterated his interest in acquiring Greenland, even raising the possibility of using tariffs or military pressure to achieve it

- EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen argued that nostalgia for the old order is futile, insisting that Europe must build a more independent stance to protect its interests

The US is not alone in elevating power over norms. In Asia, China’s actions around Taiwan and Japan likewise demonstrate a readiness to ignore or twist rules in favour of hard power and coercion. Last December, Beijing launched its largest-ever military drills encircling Taiwan, an exercise dubbed “Justice Mission 2025.” Over two days, the People’s Liberation Army effectively simulated a blockade and strikes on Taiwan, sending dozens of warships and aircraft to menace the island’s air and sea approaches.

The timing was no accident. China’s show of force came shortly after Japan’s new Prime Minister, Sanae Takaichi, had suggested Tokyo might respond militarily if China attacked Taiwan, calling a Taiwan contingency potentially “existential” for Japan. More concretely, Beijing turned to economic punishment. It banned imports of Japanese seafood and urged Chinese tourists to shun Japan. This pattern of economic coercion has become Beijing’s hallmark in recent years. It underscores a broader reality: when formal international mechanisms fail to deliver outcomes Beijing wants, China increasingly relies on its own economic clout to impose costs.

And then, there is Russia’s war in Ukraine, the most open breach of international law in the modern era. Nearly three years after invading its neighbour, Russia continues offensive operations on Ukrainian soil, having openly annexed large swathes of territory by force. This is a textbook violation of the UN Charter’s core prohibitions on aggression and territorial conquest. Yet Moscow persists, effectively betting that its military power and nuclear-backed leverage will outlast the world’s willingness to enforce the law.

In effect, a permanent member of the Security Council is openly flouting the fundamental rules of that Council, demonstrating that, without great-power consensus, international law alone cannot stop a determined aggressor. Russia’s behaviour fits a broader pattern in which powerful states, from democracies to autocracies, show a willingness to override norms when those norms constrain their goals.

Mid Powers on the Menu

These events underscore a crucial point of debate in contemporary international affairs: The distinction between a “rules-based order” and actual international law. The former term, popularised by Western diplomats, implies a political commitment by influential states to uphold certain norms and institutions. However, it has always been somewhat selective; it often meant rules set by the West, which were observed by others. International law, on paper, is more universal. The UN Charter, treaties, and legal conventions apply to all.

Yet international law lacks an enforcement arm independent of state power. It operates largely on consent and collective enforcement. Now that the consensus has fractured, what we are witnessing is not a wholesale abandonment of international law, but rather its hollowing-out and manipulation. Laws and institutions still exist, but their effect increasingly depends on who is backing them at any given moment.

- The US launched a unilateral operation in Caracas, Venezuela, aimed at deposing President Nicolás Maduro, capturing him and his wife

- Last December, Beijing conducted its largest-ever military drills encircling Taiwan, dubbed ‘Justice Mission 2025,’ deploying dozens of warships and aircraft to threaten the island’s air and sea approaches

Facing this new landscape, countries lacking superpower clout are seeking ways to adapt. In Davos, Canada’s Prime Minister Mark Carney, a banker-turned-politician, emerged as a leading voice urging middle powers to unite in defence of a stable order. “We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition,” Carney warned fellow leaders, describing the old US-led system as effectively broken.

He argued that countries like Canada must work together to constrain superpower excesses. “If great powers abandon even the pretence of rules and values for the unhindered pursuit of their interests, the gains from transactionalism will diminish,” he said. Notably, Carney called on “the world’s middle powers” to cooperate, warning that “if you are not at the table, you are on the menu”.

Leaders across Europe echoed similar themes. French President Emmanuel Macron, in his Davos speech, spoke of a coming “world without rules” where “international law is trampled underfoot” and the only law that matters is that of the “strongest”. Macron made clear that Europe must strengthen itself, militarily and economically.

European Union chief Ursula von der Leyen likewise asserted that nostalgia for the old order is futile. Europe must build “a more independent Europe” to secure its interests. Such voices show a recognition across traditional Western allies that the system they took for granted is breaking, and that they cannot simply rely on Washington’s leadership or on international law to save it.

Virtues of Multilateralism

There is a certain irony in figures like Carney or Macron championing these ideals. Countries such as Canada and France were among the core architects and beneficiaries of the post-1945 liberal order. They could take for granted that international law and institutions would function, largely backed by US power. Now, confronted by an American president who himself threatens these very foundations, they are rediscovering the virtues of multilateralism and restraint.

Meanwhile, many non-Western nations have been raising such concerns for decades. Nations of the Global South, in particular, have long emphasised sovereignty, non-intervention, and the equality of states, partly because they lacked a superpower to guarantee their security, and saw international law as a shield against imperial overreach.

- China’s show of force followed remarks by Japan’s new Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi, who suggested that Tokyo might respond militarily if China attacked Taiwan, calling a Taiwan contingency potentially “existential” for Japan

For example, India has consistently championed the importance of a rules-based international system in which no state can dictate to others. Indian leaders, from Jawaharlal Nehru onwards, have supported the UN and upheld principles of territorial integrity and non-aggression. Just last year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, even while balancing ties between Russia and the West, reiterated that India “remains committed to upholding the UN Charter, international law, sovereignty and territorial integrity” in global affairs.

India often invokes these principles not out of abstract idealism but out of enlightened self-interest. As a still-emerging power, it seeks a world where it can rise without being crushed or coerced by a stronger rival. The language of rules and principles long used by the ‘Third World’ and Non-Aligned Movement is being picked up by Western voices who suddenly feel exposed.

A realist might note that states bend the rules whenever they have the power and incentive to do so. Moreover, institutions like the United Nations still provide forums where even middle powers can block collective action. In other words, the ‘rules-based order’ has always contained inconsistencies, and middle powers have at times contributed to them.

Yet, what distinguishes the current moment is the sense that the guardrails are coming off at the system-wide level, not just in isolated incidents. The world had witnessed episodes of norm erosion before, but today’s erosion appears broader and harder to reverse because it coincides with massive shifts in economic and military power, and a sort of normative fatigue after repeated disappointments.

Holding the Line

Where does this leave countries like India, which finds itself both a rising power and a stakeholder in a rule-based system? Interestingly, India’s long-standing doctrine of “strategic autonomy” may serve it well in this more Hobbesian world. For years, India refused to align fully with any bloc, choosing not to join military alliances and keeping the freedom to make decisions on a case-by-case basis. This stance was sometimes viewed sceptically by Western nations, which hoped to see India firmly on the side of the ‘liberal order’.

But in an era when that order is fracturing, India’s strategy of maintaining independence looks prudent. Moreover, India has been vocal about reforming international institutions, arguing that the post-1945 structures no longer reflect current realities. Now, with Western countries themselves acknowledging the failures of these institutions, India’s calls for a new global governance architecture find a more receptive audience.

The reality is that stability in the international system will not be restored by those openly breaking the rules or seeking to rewrite them unilaterally. Neither a declining superpower that invokes rules one day and violates them the next, nor an ascendant authoritarian power that views rules as a Western imposition, can be expected to suddenly act as guarantors of global order. Instead, any hope for a more predictable and law-respecting world lies with countries that still have a stake in common rules and, importantly, are still on their way up, such as the Global South and developing nations.

Middle and emerging powers — from India and Indonesia to Brazil — stand to lose the most in an anarchic, power-centric world. If they fail, the world risks sliding into an openly power-centric world reminiscent of past centuries but with far deadlier weapons. In such a world, ‘might’ rules, and ‘rights’ are optional.

As Canada’s Prime Minister warned, “nostalgia is not a strategy.” The world will not simply return to the comfortable rules of yesterday. If enough nations still value rules, they must work creatively to uphold them across power divides — or risk living in a place where law and morality are always at the mercy of the strongest.

(The author is Assistant Professor, Symbiosis Law School, Pune and Young Leader, Pacific Forum, USA)

Related News

-

Rewind: Crude power — Iran war and the global oil shock

-

Melania Trump expounds idea of ‘single digital nation-state’ at historic UNSC meet

-

US, Israel clash with Iran in UNSC, as UN chief Guterres warns of uncontrollable ‘chain of events’

-

Rewind: Kaleshwaram’s Treasures — Temples, Tussar, Three Rivers

-

Kerosene and coal return as West Asia crisis disrupts India’s fuel supplies

2 mins ago -

Ruckus at Prajapalana programme as BRS sarpanches confront Congress MLA

44 mins ago -

Hyderabad: Youth arrested for murder of job consultancy owner in Madhura Nagar

46 mins ago -

BRS urges SEC to complete polling at Ibrahimpatnam, Kyathanpalli municipalities

49 mins ago -

Restaurant fined Rs.15,000 after cockroach found in meal in Siddipet

59 mins ago -

Hyderabad: Traffic diversions announced near Ashok Nagar from March 13

1 hour ago -

CPI(M) demands clearance of Rs.7,500 crore fee reimbursement dues

1 hour ago -

Fuel panic spreads as queues form at pumps and LPG outlets across India

1 hour ago