Opinion: Plans don’t make cities work. Managers do

Good cities are built not only through vision, but through everyday competence

By Dr Tarun Arora, Dr Reetika Syal

Indian cities are surrounded by plans, yet struggle with performance. Almost every major city today has a Master Plan, a Mobility Plan, a Smart City proposal and, increasingly, a Climate Action Plan. These documents are often technically sound, prepared by experts and supported by data. They reflect serious institutional effort and political intent. Yet daily urban life tells a different story.

Also Read

Traffic congestion worsens year after year in Bengaluru and Hyderabad. Flooding has become a recurring feature of the monsoon in Mumbai and Chennai. Pub lic transport remains unreliable across most cities. Air quality routinely dips into hazardous levels every winter in Delhi and is steadily deteriorating in several Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities as well.

For many residents, the lived experience of the city feels disconnected from the promises embedded in official plans. The proliferation of plans has not translated into predictability, reliability or safety in everyday urban services. This persistent gap reveals a fundamental paradox. Indian cities do not suffer from a lack of planning. They suffer from a lack of effective urban management that can translate plans into outcomes.

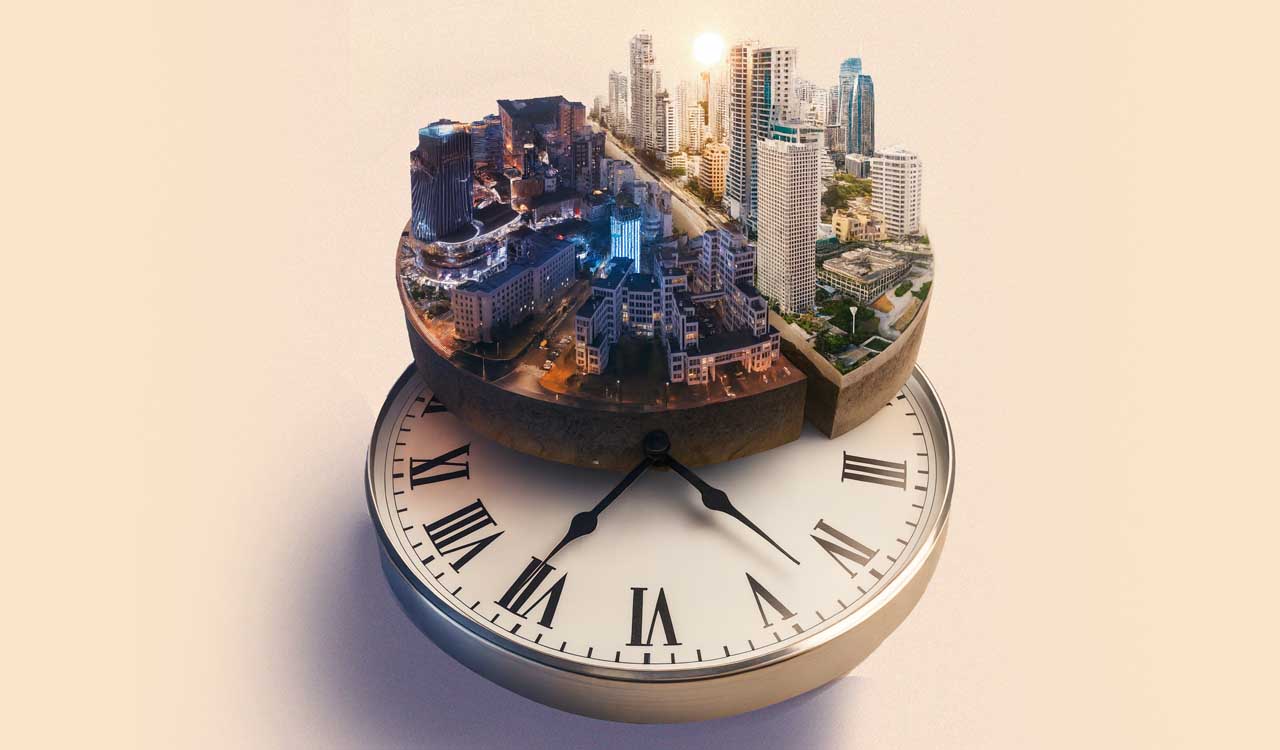

Cities as Living Systems

Urban planning has historically treated cities as spatial objects that can be designed, regulated and stabilised over long periods. Zoning maps, land-use regulations, and development controls assume that urban growth follows predictable trajectories and that once rules are set, cities will conform to them. While this approach is necessary to prevent chaos, it is inherently limited. Cities are living systems shaped by migration, labour markets, real estate dynamics, climate risks and everyday human behaviour. They change continuously and often unpredictably.

Informal settlements expand on city edges, travel patterns shift with the emergence of new employment hubs, land uses evolve, and infrastructure systems are constantly stressed. Air pollution levels respond not only to emissions standards on paper, but to traffic enforcement, construction practices, waste burning and regional coordination. A plan may imagine how a city should look 20 years from now, but it cannot manage how the city functions tomorrow morning. Managing a living system requires constant monitoring, coordination and adjustment. These tasks are less about design and more about governance, and they fall largely outside the remit of conventional planning institutions.

Planning Is Periodic, Management Continuous

Urban planning is episodic by design. A Master Plan is prepared once every decade or two, debated, notified after legal processes and then frozen until the next revision cycle. This structure assumes that cities evolve slowly and can be guided through periodic intervention. Urban life, however, does not follow planning cycles.

Water must reach households daily. Garbage must be collected every morning. Traffic must be managed every hour. Drains must be cleared before every monsoon, not after floods occur. Public transport must function reliably, not just exist in proposals or tender documents. Air quality must be monitored daily, construction dust must be controlled consistently, and waste burning must be prevented every night.

Street lighting, footpaths, sanitation and public spaces require routine attention rather than one-time interventions. These everyday tasks require institutions that operate continuously and respond in real-time. When planning dominates urban governance without corresponding management capacity, cities excel at producing documents but struggle to deliver services.

Fragmented Governance and Management Failure

Most Indian cities operate through fragmented governance arrangements. Transport, water supply, sanitation, housing, electricity, roads and pollution control are managed by different agencies, often reporting to different departments. Planning may be undertaken by one authority, while execution is scattered across several others. Municipal bodies are expected to manage outcomes without adequate authority, staffing or access to data. In such systems, accountability becomes diffused and coordination weak.

Cities are living systems shaped by migration, labour markets, real estate dynamics, climate risks and everyday human behaviour. Managing it requires constant monitoring, coordination and adjustment

When problems arise, responsibility is passed across agencies, and corrective action is delayed. This fragmentation explains why many urban problems persist despite repeated efforts at planning. Traffic congestion continues because enforcement and coordination are weak. Flooding recurs because maintenance is neglected and responsibilities are unclear. Air quality deteriorates because monitoring, enforcement, construction regulation and regional coordination do not move in sync. Infrastructure projects are completed, but service quality remains inconsistent. The result is a city that appears active on paper but struggles in practice. These are not failures of vision or expertise. They are failures of management embedded in institutional design.

Planners and Managers: Distinct but Complementary

This argument is not a rejection of urban planning. Cities need planners to guide growth, regulate land use and prevent long-term spatial distortions that are costly to reverse. Without planning, urban development becomes chaotic, inefficient and exclusionary. However, planners cannot be expected to manage daily urban operations. The skill sets required are fundamentally different.

Planning focuses on spatial design, regulation and long-term vision. Management focuses on coordination, performance, accountability and service delivery. Indian urban governance has invested heavily in planning capacity through master plans, consultants and specialised agencies, while neglecting the development of professional urban managers within municipal systems. As a result, cities often have clear plans but weak operational control. Projects are sanctioned, but timelines slip. Infrastructure is created, but maintenance is poor. Pollution norms exist, but enforcement is inconsistent.

Systems exist, but accountability is diffuse. Cities need managers who can work across departments, manage contracts and budgets, track service performance, and monitor indicators such as AQI, intervening quickly when systems fail. Without this management layer, planning remains aspirational rather than operational, and urban reform remains incomplete.

From Plans to Performance

For urban residents, governance is experienced through outcomes, not documents. Citizens do not interact with Master Plans or zoning regulations. They interact with water taps, buses, footpaths, pollution alerts and frontline officials. Reliability, responsiveness and fairness shape public trust in urban institutions far more than policy intent.

In an era of rapid urbanisation, intensifying climate stress and rising citizen expectations, the cost of poor management is increasing. Cities can no longer afford repeated failures of coordination, maintenance and service reliability. Urban reform must, therefore, shift its focus from producing plans to ensuring performance. This requires investing in urban management capacity, strengthening municipal institutions, improving data systems and redefining success in terms of service outcomes rather than project announcements. It also requires recognising that good cities are built not only through vision, but through everyday competence.

Urban planning will always matter, but it cannot substitute for urban management. Plans may design cities, but only managers can make them work.

(Dr Tarun Arora is Associate Professor and Associate Dean, Jindal School of Government and Public Policy, OP Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana. Dr Reetika Syal is Assistant Professor, Department of International Studies, Political Science, and History Christ University, Bengaluru)

Related News

-

Telangana Cabinet decisions: Metro, water projects and new schemes

1 min ago -

PM Modi writes to Bengal voters, promises economic revival

2 mins ago -

Tamil Nadu electoral roll revised, 97.37 lakh names removed

9 mins ago -

Centre approves Rs 2,432 crore for Amended BharatNet in Andhra Pradesh

13 mins ago -

Minister urges RTC employees to withdraw protests

60 mins ago -

Woman killed in road crash

1 hour ago -

RTC employees to conduct ‘Chalo Secretariat’ on Tuesday

1 hour ago -

Now you can borrow helmet from Helmet Bank and return it later, initiative launched

1 hour ago