Opinion: Trifurcating GHMC is not reform — it is institutional weakening

Breaking up GHMC will shrink consolidated tax base, dilute professional capacity, weaken borrowing power, and deepen fiscal dependence on the state

By Pendyala Mangala Devi

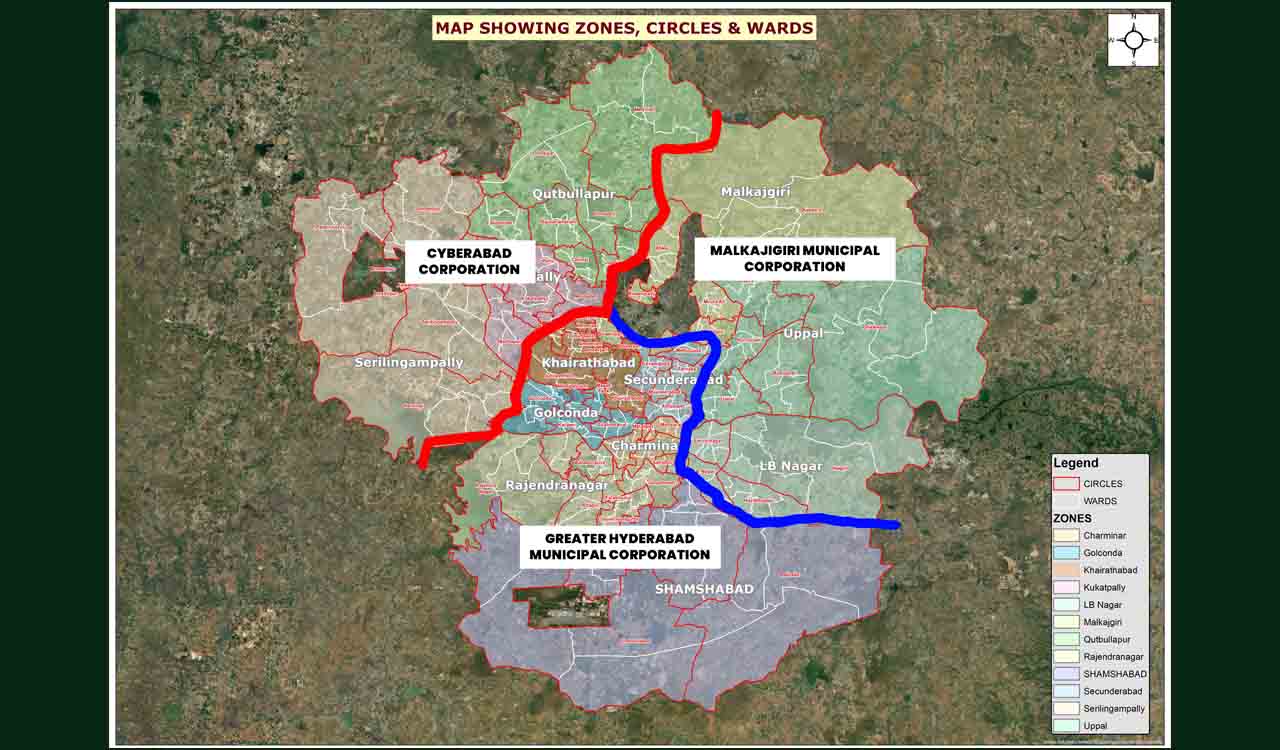

The proposal to trifurcate the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) is being marketed as administrative efficiency. We are told it will ensure “better service delivery,” “manageable size,” and “closer administration.” These phrases sound modern. They are politically attractive. But they are structurally hollow. Beneath them lies a misunderstanding of how cities function, a selective reading of constitutional design, and a willingness to weaken democratic institutions instead of repairing them.

Also Read

Jawaharlal Nehru warned that “Democracy is not merely a form of government; it is a way of life.”

In cities, democracy is not abstract. It is drainage that works, waste that is collected, roads that are maintained, and water that reaches households. Urban governance is where democracy becomes visible. When the institution governing a city is weakened, democracy erodes in practice.

A City Is an Integrated Organism, Not an Administrative Map

At the heart of the trifurcation argument lies a fundamental error: treating a city as an administrative map rather than as an integrated system. A city is not a set of wards stitched together by notification. It is a dense, interdependent organism — labour markets linked to transport corridors, drainage networks tied to topography, housing patterns intertwined with employment zones.

Writer and urban activist Jane Jacobs described cities as “problems in organized complexity”. Organised complexity demands institutional integration, not fragmentation.

Plato warned that when internal unity collapses, governance descends into disorder (The Republic, Book IV). Fragmentation weakens the coherence that makes metropolitan governance possible.

Constitutional Architecture of Urban Self-Government

The constitutional dimension makes the issue more serious. The 74th Constitutional Amendment inserted Part IX-A (Articles 243P–243ZG) into the Constitution, granting constitutional status to municipalities and municipal corporations. These are not administrative conveniences of State governments. They are institutions of self-government, elected by the people, with functions explicitly listed in the Twelfth Schedule — including urban planning, regulation of land use, water supply, sanitation, public health, slum improvement, and urban forestry.

The 73rd and 74th Amendments were enacted precisely to deepen democracy by empowering villages and cities as constitutional units of governance.

The False District Analogy: Administrative Divisions vs Constitutional Governments

One of the most common justifications for trifurcation is deceptively simple: States create new districts for administrative convenience. Why not create new municipal corporations? Because districts are not constitutional governments.

Real reform strengthens institutions; it does not divide them. Delhi’s experience shows how fragmentation undermines financial stability, accountability, and metropolitan governance

Districts are administrative divisions created under state laws and executive authority. A District Collector is appointed by the State government. A district does not derive authority from Part IX or Part IX-A of the Constitution. It is an arm of the executive.

Village panchayats derive authority under Part IX (Articles 243–243O). Municipalities and Municipal Corporations derive authority under Part IX-A. Their tenure, elections, composition, and functions are constitutionally protected. The Supreme Court in Kishansing Tomar v. Municipal Corporation of Ahmedabad (2006) underscored that municipalities are constitutional institutions whose democratic continuity cannot be casually interrupted.

Equating the creation of districts with the fragmentation of municipal corporations is, therefore, constitutionally inaccurate. Districts are administrative subdivisions. Municipal corporations are democratic governments. Treating a city like a district is not reform. It is constitutional confusion.

What the Evidence Says: Ahluwalia Committee’s Warning

The High-Powered Expert Committee (HPEC) on Urban Infrastructure and Services (2011), chaired by Dr Isher Judge Ahluwalia, stated unequivocally: “The weakness of India’s cities lies not in their size, but in the inadequacy of their governance structures and finances.” (HPEC Report, 2011)

The Committee warned against fragmentation and overlapping jurisdictions. Breaking GHMC into smaller corporations would shrink consolidated tax bases, dilute professional cadres, reduce borrowing capacity, and increase fiscal dependence on the state. That is not decentralisation; it is institutional weakening.

French political thinker Alexis de Tocqueville observed, “Local institutions are to liberty what primary schools are to science.” Hollow out local institutions, and liberty itself becomes fragile.

Delhi: A Real-World Experiment in Fragmentation

If one needs a practical illustration of fragmentation’s consequences, Delhi provides it. In 2012, the Municipal Corporation of Delhi was trifurcated into North, South, and East corporations under the Delhi Municipal Corporation (Amendment) Act, 2011. The official reasoning echoed today’s language: better administration, greater efficiency. The outcome was a structural imbalance.

South Delhi inherited affluent commercial areas and stronger property tax bases. North and East Delhi inherited larger populations with weaker revenue sources. The result was chronic fiscal distress. Salaries of municipal staff and sanitation workers were delayed repeatedly. Garbage crises became routine. Service delivery faltered not because Delhi was too large, but because it had been divided without fiscal symmetry.

Administrative coordination also deteriorated. Delhi already had multiple agencies — the Delhi Development Authority, NDMC, Cantonment Board, Public Works Department, and central authorities. Trifurcation multiplied institutional fragmentation. Metropolitan problems required metropolitan coordination, but governance became fractured across competing municipal entities.

The HPEC had warned that “multiple agencies with overlapping responsibilities have led to weak accountability and poor service outcomes in metropolitan governance.” Delhi illustrated this with precision. Political fragmentation compounded the dysfunction. Different corporations were controlled by different parties while the State government was led by another. Accountability dissolved into blame-shifting. Citizens were caught between institutions, pointing fingers at one another.

Max Weber warned that bureaucracy without clarity of authority degenerates into dysfunction. Delhi’s municipal fragmentation demonstrated that lesson.

In 2022, Parliament enacted the Delhi Municipal Corporation (Amendment) Act, reunifying the three corporations into a single entity. The stated reasons included financial instability, duplication of administrative structures, and governance inefficiency. Reunification was not ideological. It was corrective. It was recognition that fragmentation had failed to produce structural improvement. To fragment and then reunify is not reform. It is governance by costly experimentation.

Metropolitan Governance Constitutionally Anticipated

The Constitution anticipated metropolitan complexity long ago. Article 243ZE mandates Metropolitan Planning Committees for coordinated planning across municipalities. The HPEC reinforced the need for unified metropolitan governance for transport, housing, and environmental management.

American statesman and political theorist James Madison warned that poorly designed institutions breed factionalism. In metropolitan governance, factionalism translates into stalled infrastructure, institutional rivalry, and public inconvenience.

Urban governance also has a political economy. Large municipal corporations possess bargaining power — financial, administrative, and political. Fragmentation weakens that leverage. The HPEC cautioned that urban local bodies are often assigned responsibilities without matching authority or finances.

What Real Reform Actually Requires

If the GHMC faces governance challenges, the solution lies in strengthening institutions: unified authority, robust property taxation, predictable fiscal transfers, professional urban cadres, and metropolitan-scale planning.

The HPEC was clear: “India needs empowered city governments with adequate financial resources, professional capacity, and political accountability.” None of this requires trifurcation.

Reform Strengthens. Retreat Divides

Delhi’s experience is not theoretical. It is recent history. It shows what happens when fragmentation is mistaken for reform. Villages, municipalities, and municipal corporations are constitutional governments. Districts are administrative divisions. Confusing the two is not innovation. It is institutional misreading.

Reform that weakens democratic institutions is not reform. It is a retreat. And retreat in urban governance always extracts its cost from citizens, not from those who design the maps.

Related News

-

Minor girl goes missing in Bhadrachalam; case registered

4 mins ago -

Ancient statue of Lord Vishnu unearthed from a stream in Bhupalpally

27 mins ago -

NIT Warangal students clash on campus over filming videos during SpringSpree event

36 mins ago -

HCCB partners with Peddapalli for rural development

44 mins ago -

Markram and Santner set for key battle in T20 World Cup semifinal

53 mins ago -

HDFC Bank revises UPI ATM withdrawal rules

1 hour ago -

Three Hyderabad bowlers invited for MRF Pace Foundation trials

1 hour ago -

Nationwide ASMITA athletics league to mark International Women’s Day at 250 locations

1 hour ago