Opinion: Can we ‘trans’form?

The absence of quota scheme for transgender individuals disconnects them from achieving political, social and economic justice

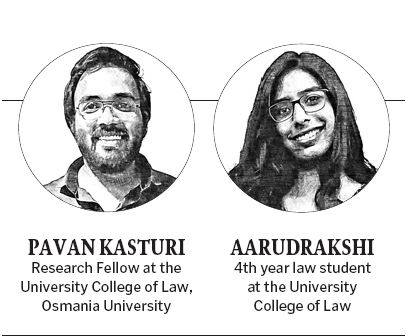

By Pavan Kasturi, Aarudrakshi

The call for women’s reservation in Indian politics was realised through the 106th Constitutional Amendment Act, reserving one-third (33%) of seats in Lok Sabha and State Legislative Assemblies. This step towards political empowerment for women is a vital tool in eliminating gender inequality and discrimination. Yet, the present juncture forces us to cast our gaze upon another marginalised community within our society, the Third Gender or the Trans community, who are thirsting for the embrace of socio-economic-political justice, tenets that are firmly enshrined in the Constitution of India.

Nehru, in the constituent assembly during the Objective Resolution speech, expressed that words possess enchantment, yet the magic of words sometimes falls short of capturing the magic of the human spirit. He implored the Assembly not to scrutinise the Resolution’s words “like lawyers,” as doing so would yield mere lifelessness.

Data Disparities

Nonetheless, when it comes to the evolution of societal consciousness on the Third Gender, vibrant expression was found in the courtroom, surrounded by the lawyers in the landmark 2014 ruling of the Supreme Court (SC) in the National Legal Service Authority (NALSA) v. union of India. The court shattered the dual gender paradigm of ‘man’ and ‘woman,’ acknowledging the existence of a ‘third gender’ and conferring upon them the weight of legal recognition, thereby safeguarding their fundamental rights.

Even with the passage of almost a decade since the ruling, the situation has shown little improvement. Data disparities persist in transgender recognition and representation.

The 2011 Census marked a significant milestone by acknowledging 4.8 million transgender individuals but fell short of capturing the full spectrum of gender identities.

The National Crime Records Bureau’s 2020 data showed minimal reported crimes against transgender individuals, but this likely reflects underreporting, not reduced crime rates. Facing everyday challenges like identity crises, exclusion, discrimination, exploitation, violence and compulsory marriage, the transgender community remains largely unaccounted for, amplifying their struggle for visibility and human rights.

TS High Court Decision

The Telangana High Court invalidated the Telangana Eunuchs Act, 1329, in V Vasanta Mogli v. State of Telangana, a petition filed by a transgender activist renowned for championing LGBTQI rights. This Act mandated the maintenance of a register for eunuchs in Hyderabad, allowing arrests without a warrant and potential imprisonment for transgender individuals engaged in various activities. In the case, the court found the Act in violation of Articles 14, 15 and 21 of the Constitution and infringing upon the rights of the transgender community.

What could have been done by the HC? Even the SC in NALSA directed the union and State governments to classify transgender as a socially and educationally disadvantaged group of citizens, thereby granting them reservations in educational institution admissions and employment appointments. The SC in 2017 and now the Telangana HC in 2023 had missed an opportunity to provide the transgenders with horizontal reservation (HR). The difference between Vertical Reservation (VR) and HR is: The VR is an affirmative action provided for the historical injustices under Article 16(4), ie, reservation for SC, ST, and OBC. While HR under Article 16(1) has special reservations for women, PWD, sports quota, etc.

The absence of a reservation scheme for transgender individuals, despite the introduction of the Transgender (Protection of Rights) Act, 2018, by Parliament, disconnects them from achieving political, social, and economic justice. Interestingly, the Karnataka government has introduced 1 per cent HR to the Third Gender.

Recently, even the Telangana HC expressed dissatisfaction for failing to implement the SC orders regarding reservations for the transgender community in educational institutions. The court addressed this issue in a NEET PG case, where the petitioner had faced challenges in accessing her rightful quota during PG course admissions.

The HC has missed a chance through which it could have made a judicial law through interpretation for the time being till the States introduce a policy for reservation. After all, Article 14 says that the State shall not deny to any person equality before the law, not men/women.

Providing HR for transgender individuals offers a more inclusive and tailored approach, recognising the unique challenges they face due to their gender identity. This promotes diversity, social inclusion, gender equity and equal opportunity while avoiding direct competition with other marginalised communities (OBCs) for limited reserved seats.

The issue of transgender reservations is rooted in matters of gender, and providing them with caste-based reservations and incorporating them into the OBC quota presents a complex dilemma. It intertwines the facets of caste and gender, creating a dual-edged predicament that places additional burdens on the already marginalised OBC communities while providing no substantial justice to the Third Gender.

Political Justice

In 1998, Shabnam Mausi made history by becoming the first transgender MLA in Madhya Pradesh. In 2000, Kamla Jaan, and in 2015, Madhu Kinnar were elected as Mayor of Sagar in Madhya Pradesh, and Raigarh (Chhattisgarh), respectively. Despite several transgender individuals contesting in the general elections of 2014 and 2019 for a Member of Parliament position, none were elected. Curiously, no State has yet sent a transgender representative to the Rajya Sabha or Lok Sabha.

Political representation and reservation for transgender are imperative because they are the embodiment of unheard voices, the heralds of marginalised narratives, and the vanguards of social change. By providing a platform within our political system, we not only acknowledge their right to participate in democracy but also ensure that the laws and policies shaping our society are more inclusive and equitable.

The absence of such representation perpetuates exclusion, discrimination, and the denial of basic human dignity. Thus, there is a moral and constitutional duty to rectify this injustice, especially in the form of reservations in educational, employment and political areas, thereby creating a democracy that truly stands for all.

Related News

-

Govt debunks deepfake video of Army Chief, warns of Pakistani disinformation campaign

6 mins ago -

Traffic inspector performs CPR after car driver suffers cardiac arrest in Secunderabad

18 mins ago -

Sangareddy police hold cyber safety awareness programme for women students

27 mins ago -

Telangana Group-I officers begin foundation course at Dr MCR HRD Institute

30 mins ago -

‘Raju weds Rambai’ fame Chaitu Jonnalagadda roped in for Dhanush’s #D55?

49 mins ago -

Mamata Banerjee accuses CEC of threatening Bengal officers at meeting

51 mins ago -

Nishant Kumar plans tour of all 38 districts of Bihar after joining JD(U)

51 mins ago -

TMC alleges voter harassment in SIR exercise as EC holds consultations in Bengal

55 mins ago