Safety nets for farmhands

Now a tangible solution would be to make amendments and provide assurances to farmers, particularly on MSP and APMCs

Reforms require changes in the existing system and so attract resistance. This is what happened with economic reforms in the early 90s and now the same is happening with agriculture.

People who support the laws may say that only farmers of Punjab are agitating because these laws affect them the most — 70-80% farm produce is procured with MSP by the Food Corporation of India. What would certainly come under pressure is the high commission of Arhtiyas, mandi fee and cess that States collect, which account for around 8.5% over the MSP in Punjab, amounting to roughly Rs 5,000 crore each year.

These laws were passed without much consultation with farmers. There is also a gross communication failure on the part of the Central government to explain to farmers what these laws are, and how they would benefit from them.

Non-Contentious Laws

Of the three laws, farmers need not worry over two. The Essential Commodities (Amendment) Act is about doing away with the Centre’s powers to impose stockholding limits on foodstuff. This Act mainly applies only to traders — the amendment exempts processors, exporters and other “value chain participants” as long as they don’t keep quantities beyond their installed capacity/demand requirements. Farmers would only gain from removal of stocking restrictions on the trade as it potentially translates into unlimited buying and demand for their produce.

The Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Act deals with providing a regulatory framework for contract cultivation. This specifically concerns agreements entered into by farmers with agri-business firms for supplying produce of predetermined quality at minimum guaranteed prices.

Again, there is little rationale for objecting to an Act that merely enables contract farming. Such exclusive agreements between companies and farmers are already operational like in tomato and potato, with multinational companies. Processors/exporters in these cases typically not only undertake assured purchases at pre-agreed prices but also provide farmers seeds/planting material and extension support to ensure that only produce of the desired standard is grown.

As per NSSO data, the average size of operational holdings in India fell to 1.2 hectares in 2010-11 from 2.3 hectares in 1970-71. China’s average holdings are even smaller. Despite the similarities, Chinese agriculture has fared better than India’s on most counts over the past few decades. Both India and China are among the world’s top three producers of important crops such as rice, wheat, cotton and maize, but China produces much more from each hectare of land than India.

China and India

In the early 1960s, farm sector indicators of India and China looked similar, but since then China has left India behind. Today in China, most of the agriculture is done by corporates. China has cleared the way for private investment in large-scale farming, announcing a change in land rights that heralds a new era for agriculture. The move to corporate farming is designed to solve two of the pressing problems of the Chinese countryside — a rapid increase in elderly farmers and poor yields from the country’s hundreds of millions of small plots.

Consolidation of farmers is very important to realise many benefits such as access to technology, credit, new skills and to be able to participate in the e-commerce market with sufficient marketable surplus. After the failure of cooperatives in Indian agriculture, contract farming holds promise for aggregation of landholdings. For addressing any pitfalls in contract farming, Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs) should be strengthened. The government has already promised to form 10,000 FPOs and these numbers should be increased.

Contentious law

Much of the opposition is for the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act. It permits sale and purchase of farm produce outside the APMC mandis. Such trades (including on electronic platforms) shall attract no market fee, cess or levy “under any State APMC Act or any other State law”.

At the heart of the farmers’ fear is the potential end of MSP and slow disappearance of APMCs. A small section of India’s farmers — most notably in Punjab — relies excessively on selling rice and wheat to the government at the so-called MSP. The purchase takes place in markets, known as ‘mandis.’ One of the laws gave farmers the freedom to sell their produce outside the designated yards — and without having to pay taxes and fees to any State government. For grain cultivators, the worry that cropped up is — “If the mandi falls into disuse, will the government stop buying from us at guaranteed prices?”

The fear is not entirely irrational. The FCI’s granaries are overflowing. The excess stock costs the taxpayer $25 billion, money that could have other uses in the post-Covid economy. Farmers know this. One of their demands is for legal backing for MSP, something that could have ugly consequences for public finances. Authorities currently announce prices for 23 commodities, but these are largely meaningless except for wheat, rice and cotton in a few States.

Since the Bills are already passed, it is not easy for any government to abolish the Act. But letting the unrest linger could cause chaos in food markets, alienate urban consumers, and potentially derail the post-Covid recovery.

Reforming Farm

Indian farming must come out of its 3% growth rut. Productivity of labour, land, fertilizer and water has to improve. Massive private investments need to take place in storage and processing for the country’s 2% share of global agricultural exports to increase. The benefits of these laws will start showing in the next 3-5 years. New experiments and models will come in to build direct supply lines connecting with farmers — either individual farmers or farmer organisations or FPOs — just like it happened in the case of milk cooperatives.

The dispute is over which strategy to pursue. Markets or organisations? That’s an old dilemma made famous by economist Ronald Coase in 1937. Modi is leaning towards markets, promising to turn the country into a free trade area benefiting 119 million farmers and 144 million farmhands, plus their families. But a large and growing number view this move as an end to institutional state support, which they fear will allow profiteering corporations to rush into the resulting vacuum.

A compromise solution would require consultation. Even those who defend the reforms agree that both their intent and benefits should have been explained better. But it’s too late for public relations.

Now a more tangible solution would be to make some amendments and provide assurances to farmers, particularly with regard to MSP and APMCs. There must be some safety valves like making any trade below MSP illegal. To resolve disputes arising from contract farming, instead of empowering Collectors, there must be a Tribunal, something like consumer courts formed with agricultural experts.

(The author is Director, Centre for Good Governance, Hyderabad)

Now you can get handpicked stories from Telangana Today on Telegram everyday. Click the link to subscribe.

Click to follow Telangana Today Facebook page and Twitter .

Related News

-

Telangana sets up Rythu Discom, liabilities of Rs 71,964 crore shifted

-

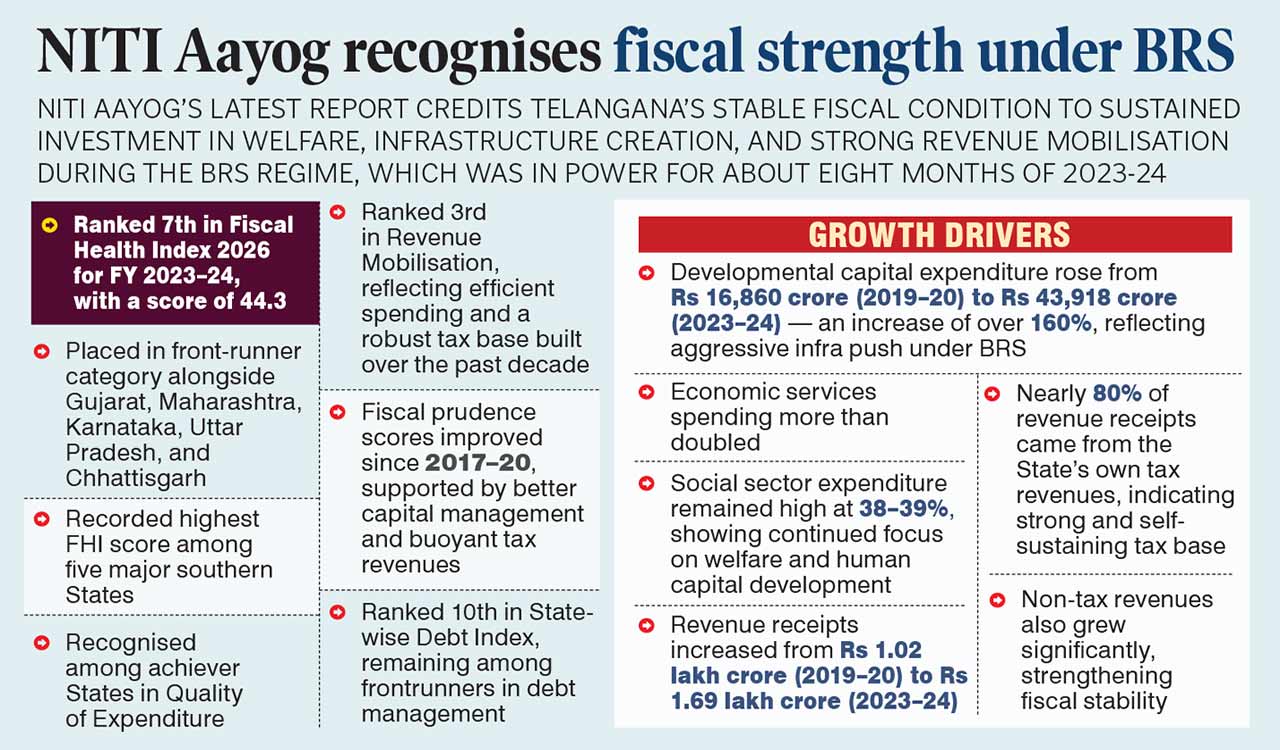

Telangana ranks 7th in NITI’s Fiscal Health Index for 2023-24, reflects BRS’ strong policies

-

Hyderabad cybercrime cracks down on 124 social media accounts promoting online betting

-

Hyderabad: Moving car catches fire on DRDL road near Chandrayangutta

-

Sports briefs: Indian boxers shine on day four at World Boxing Futures Cup

4 mins ago -

Nikki Pradhan achieves another milestone, completes 200 international caps

11 mins ago -

Iran targets ships, Dubai airport in Gulf escalation

27 mins ago -

FIH Qualifiers: India scores big win against Wales, storm into semifinal

19 mins ago -

India allows FDI under automatic route for firms with less than 10 per cent Chinese stake

51 mins ago -

IEA agrees to record emergency oil release to calm global prices

57 mins ago -

SFI students protest alleged ABVP attack in HCU hostel

1 hour ago -

Godrej Enterprises hosts GeeVees Awards 2026 to honour architects and designers

1 hour ago